Dear Readers,

As theLabor Day weekend approaches let us all pause and give belated thanks to our immigrant parents, grandparents or great grandparents for making the decision to leave home and family behind in search of a better life and, although they made the sacrifices, we are the ones reaping the benefits.

I have always felt that, although the accomplishments of our modern day astronauts and their trip to the moon are worthy of our admiration, their voyage was undertaken with the backup of thousands, both in personnel and technology.

To me, the real pioneers of travel were our fathers and mothers and our grandparents who left their isolated and obscure villages to begin a journey to what was for them like another planet.

To a world thousands of miles away, they set out with no money and the added burden of not being able to read or speak one of the world’s most difficult languages and, in some cases, unable to read at all.

The fact that we are here in our own homes, with food on the table and leisurely reading our copy of L’Italo-Americano is an Old World dream fulfilled and honored. Through the efforts of our Italian American Media and our Italian cultural groups, we can be assured that our children will never forget what our modern day media has ignored, neglected or distorted: the history and brilliance of the Italian gifts to world civilization.

***

Many immigrant dreams were dashed by the reality that greeted them upon arrival in New York, Massachusetts and other states on the Eastern seaboard. In Lawrence, Massachusetts, some 28 miles from Boston, Lawrence became home for many different immigrant communities because of the plentiful jobs from its burgeoning textile industry. Miles and miles of textile mills were built in Lawrence. This was the city that produced the textiles that clothed the nation and the world. However, in order to keep the wheels moving, the mills depended upon thousands of low-skilled laborers, mostly immigrants arrived during the great wave of European immigration to America that ended in the early 1920s, when the United States imposed a quota on the flow of immigration from Italy to America: in fact some Italians traveled to France so they could sail to America from there as no quota on immigrants to the United States from France had been imposed.

Prior to 1920, thousands of Italian immigrants had been attracted to Lawrence by posters all across the regions of southern Italy promoting the city as a place where immigrants could find good work and economic prosperity.

One poster read:

“No one goes hungry in Lawrence. Here all can work, all can eat.”

Upon their arrival, however, the thousands of Italian immigrants realized that they had been seriously deceived by the fake posters.

Living conditions were so horrendous that mill workers could expect an average life-span of only 35 years. The work week consisted of 56 hours for $6.50 a week. Rental for dilapidated housing, which was little more than a cold-water flat, was about $3 a week. So, families shared rental space. They cooked and slept in shifts.

In order to survive, everybody in the family who could work had to work. However, the miserably crowded conditions gave rise to a host of diseases, which accounted for the early death rate.

Working conditions in the mills were extremely unsafe, hours were long, Social Security did not exist at the time, and there was no compensation for work-associated accidents.

***

It all came to a head on January 12, 1912, when a new law took effect, which reduced the maximum work week from 56-54 hours.

However, the textile mill owners were not about to suffer any financial loss. They sped up the wheels of production to make up for the lost hours. That was bad enough, but it got worse when they cut the workers’ pay by two hours.

The two-hour difference came to thirty-two cents a week, the cost of four loaves of bread.

So, once the deduction appeared in their checks, workers were furious.

It began with the Italians and the Polish who hollered: “Short pay. Everybody out.”

And so, the famous Bread and Roses Strike began. However, this time Italians led the two-month strike affecting 28,000 people who spoke over 45 different languages.

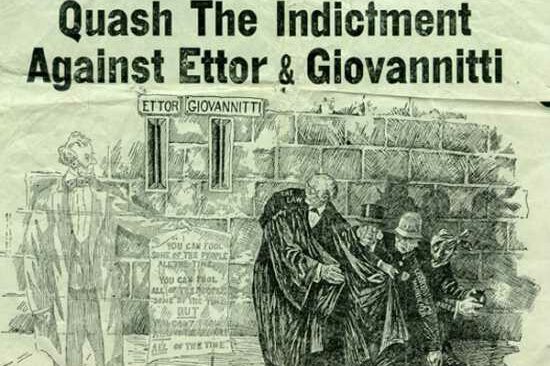

Skilled organizers Joseph Ettore and Arturo Giovanitti from the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW), rushed to Lawrence to represent the striking workers. The IWW struck fear into local and state leaders since it was socialist, some would say communist, in its leanings.

At the Mayor’s request, the Governor sent in uniformed state militia, armed with guns and bayonets to protect the mills and block the striking workers. The militia also included many student volunteers from Harvard University. Clashes resulted, the armed militia and the Lawrence police on one side and the unarmed strikers on the other side.

Law and order became impossible to maintain. Thousands of angry strikers courted confrontation and defied the militia by daily marches through the streets.

Finally, acting to keep their children out of danger, Italian parents sent 240 children by train from Lawrence to New York City where strangers volunteered to serve as host families. The children were housed, fed, and well-cared for until the strike was over.

The sight of the underfed, shabby looking, pitiful Italian children marching through the streets of New York shocked the nation. Newspaper headlines of innocent children moved Congress to hold hearings. The mill owners capitulated, and the strike ended in March of 1912.

The workers won a series of pay increases and better working conditions, The Lawrence Textiles mill strike, aka The Bread and Roses Strike, has been immortalized in poetry and song.

Cari lettori,

con l’approssimarsi del weekend del Labor Day, la festa del lavoro, prendiamoci tutti una pausa e ringraziamo pur se in ritardo i nostri genitori, nonni o bisnonni immigrati per aver deciso di lasciare casa e famiglia per andare in cerca di una vita migliore e, nonostante siano stati loro a fare i sacrifici, siamo noi a raccoglierne i frutti.

Ho sempre pensato che, sebbene i risultati dei nostri moderni astronauti e il loro viaggio sulla Luna siano degni di tutta la nostra ammirazione, il loro viaggio è stato intrapreso con il sostegno di migliaia di persone, sia in termini di personale che di tecnologia.

Per me, i veri pionieri del viaggio sono stati i nostri padri e le nostre madri e i nostri nonni che hanno lasciato i loro villaggi isolati e sconosciuti per iniziare un viaggio verso quello che per loro era come un altro pianeta. Verso un mondo a migliaia di chilometri di distanza, sono partiti senza soldi e con il fardello aggiuntivo di non essere in grado di leggere o parlare una delle lingue più difficili del mondo e, in alcuni casi, di non saper leggere affatto.

Il fatto di essere qui a casa nostra, con il cibo in tavola e la piacevole lettura della nostra copia de L’Italo-Americano è un sogno realizzato ed esaudito del Vecchio Mondo. Grazie all’impegno dei nostri media italo-americani e dei nostri gruppi culturali italiani, possiamo essere certi che i nostri figli non dimenticheranno mai ciò che i nostri media moderni hanno ignorato, trascurato o distorto: la storia e la genialità dei doni italiani alla civiltà mondiale.

***

Molti sogni degli immigrati sono stati infranti dalla realtà che li ha accolti all’arrivo a New York, nel Massachusetts e in altri Stati della costa orientale. In Massachusetts, a circa 28 miglia da Boston, Lawrence accolse molte comunità di immigrati, grazie all’abbondante lavoro della sua fiorente industria tessile. A Lawrence sono stati costruiti chilometri e chilometri di fabbriche tessili. E’ stata la città che ha prodotto i tessuti che hanno vestito la nazione e il mondo. Tuttavia, per mantenere in movimento i suoi ingranaggi, le fabbriche dipendevano da migliaia di lavoratori poco qualificati, per lo più immigrati arrivati durante la grande ondata di emigrazione europea verso l’America che si concluse nei primi anni Venti, quando gli Stati Uniti imposero una quota sul flusso di immigrazione dall’Italia verso l’America: infatti alcuni italiani si recarono in Francia per poter da lì navigare verso l’America, poiché non era stata imposta alcuna quota sugli immigrati verso gli Stati Uniti in partenza dalla Francia.

Prima del 1920, migliaia di immigrati italiani furono attratti da Lawrence da manifesti messi in tutte le regioni del sud Italia che promuovevano la città come luogo dove gli immigrati potevano trovare un buon lavoro e prosperità economica.

Un manifesto diceva: “Nessuno soffre la fame a Lawrence. Qui tutti possono lavorare, tutti possono mangiare”.

Al loro arrivo, però, migliaia di immigrati italiani si resero conto di essere stati pesantemente ingannati da manifesti falsi.

Le condizioni di vita erano così orribili che i lavoratori delle fabbriche potevano aspettarsi una vita media di appena 35 anni. La settimana lavorativa consisteva in 56 ore per 6,50 dollari alla settimana. L’affitto di una casa fatiscente, poco più di un appartamento con acqua fredda, era di circa 3 dollari a settimana. Quindi, le famiglie condividevano lo spazio in affitto. Cucinavano e dormivano a turni.

Per sopravvivere, tutti i membri della famiglia che potevano lavorare dovevano lavorare. Tuttavia, le condizioni di misero affollamento diedero origine a una miriade di malattie, che incisero sul tasso di mortalità precoce.

Le condizioni di lavoro nelle fabbriche erano estremamente insicure, le ore di lavoro lunghe, la previdenza sociale all’epoca non esisteva e non c’era alcun risarcimento per gli infortuni sul lavoro.

***

I nodi vennero al pettine il 12 gennaio 1912, con l’entrata in vigore di una nuova legge, che riduceva la settimana lavorativa massima da 56 a 54 ore.

I proprietari delle fabbriche tessili, tuttavia, non subirono alcuna perdita finanziaria. Accelerarono le linee di produzione per recuperare le ore perdute. Questo era già abbastanza grave, ma peggiorò quando ridussero di due ore lo stipendio degli operai. La differenza di due ore era di trentadue centesimi alla settimana, il costo di quattro pagnotte. Così, una volta che la detrazione apparve nelle loro paghe, gli operai si infuriarono.

Cominciarono gli italiani e i polacchi che urlarono: “Paga tagliata. Tutti fuori”.

E così iniziò il famoso Sciopero del Pane e delle Rose. Questa volta furono gli italiani a guidare lo sciopero di due mesi che coinvolse 28.000 persone che parlavano più di 45 lingue diverse.

Gli abili sindacalisti Giuseppe Ettore e Arturo Giovanitti dell’Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), si precipitarono a Lawrence per rappresentare i lavoratori in sciopero. IWW mise paura ai leader locali e statali perché era socialista, alcuni direbbero comunista, nel suo orientamento.

Su richiesta del sindaco, il governatore inviò una milizia statale in uniforme, armata di fucili e baionette per proteggere le fabbriche e bloccare i lavoratori in sciopero. La milizia comprendeva anche molti studenti volontari dell’Università di Harvard. Seguirono gli scontri, la milizia armata e la polizia di Lawrence da un lato e gli scioperanti disarmati dall’altro.

La legge e l’ordine divennero impossibili da mantenere. Migliaia di scioperanti arrabbiati cercarono lo scontro e sfidarono la milizia con marce quotidiane per le strade.

Alla fine, per mettere al sicuro i loro figli, i genitori italiani mandarono 240 bambini in treno da Lawrence a New York City, dove sconosciuti si offrirono volontari come famiglie ospitanti. I bambini furono ospitati, nutriti e ben curati fino alla fine dello sciopero.

La vista dei bambini italiani denutriti, dall’aspetto malandato e pietoso, che marciavano per le strade di New York scioccò la nazione. I titoli dei giornali sui bambini innocenti spinse il Congresso a tenere audizioni. I proprietari delle fabbriche capitolarono, e lo sciopero terminò nel marzo del 1912. I lavoratori ottennero una serie di aumenti salariali e migliori condizioni di lavoro. Lo sciopero della fabbrica tessile Lawrence Textiles, noto anche come Sciopero del Pane e delle Rose, è stato immortalato in poesie e canzoni.