I’m a book person, having devoted pretty much all of my adult life to them in one capacity or another, from working as the book-buyer and manager of independent bookstores, to editing them, to publicizing them, to writing them. And while I appreciate the portability of e-books, I’m convinced that printed books remain the best way of accessing (and enjoying) significant material. Indeed, numerous recent studies have shown that readers’ retention and comprehension of material read on paper surpasses that of readers using electronic devices.

Yet, in spite of all this, I must say I can’t imagine a better presentation of the work of one of the greatest minds humankind has ever produced than Touchpress’s recently updated application for iPads entitled Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomy. To present in book form all 268 of Leonardo’s anatomical drawings as clearly as this application manages to do on a screen would require a large, heavy and costly printed edition. But the 268 high-resolution reproductions are just the beginning of what this excellent app has to offer.

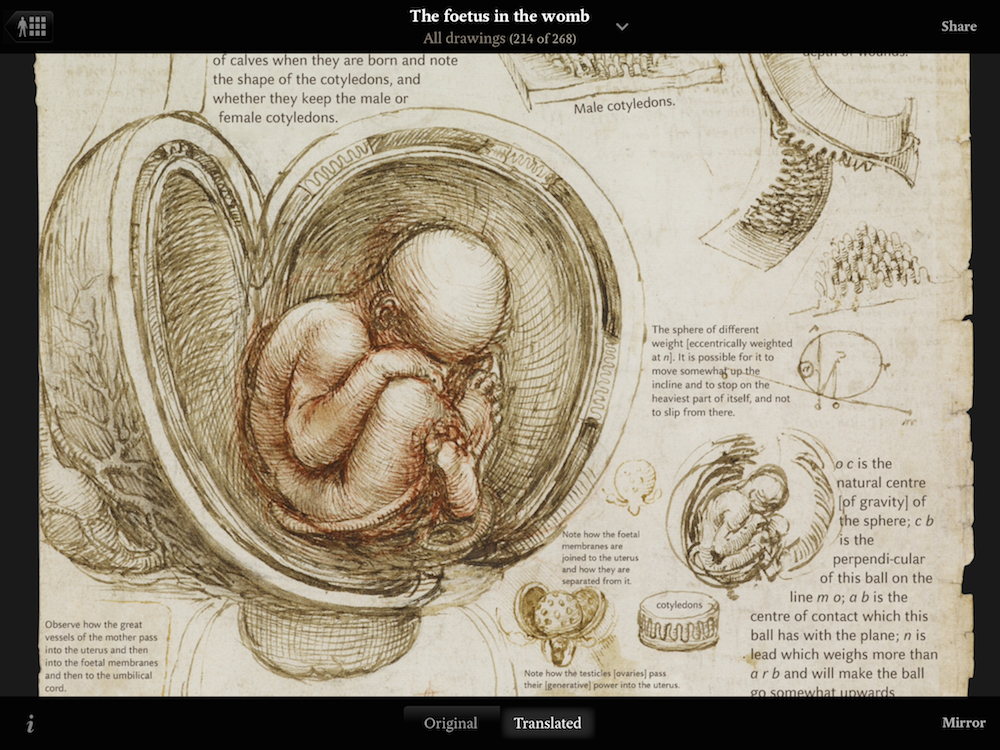

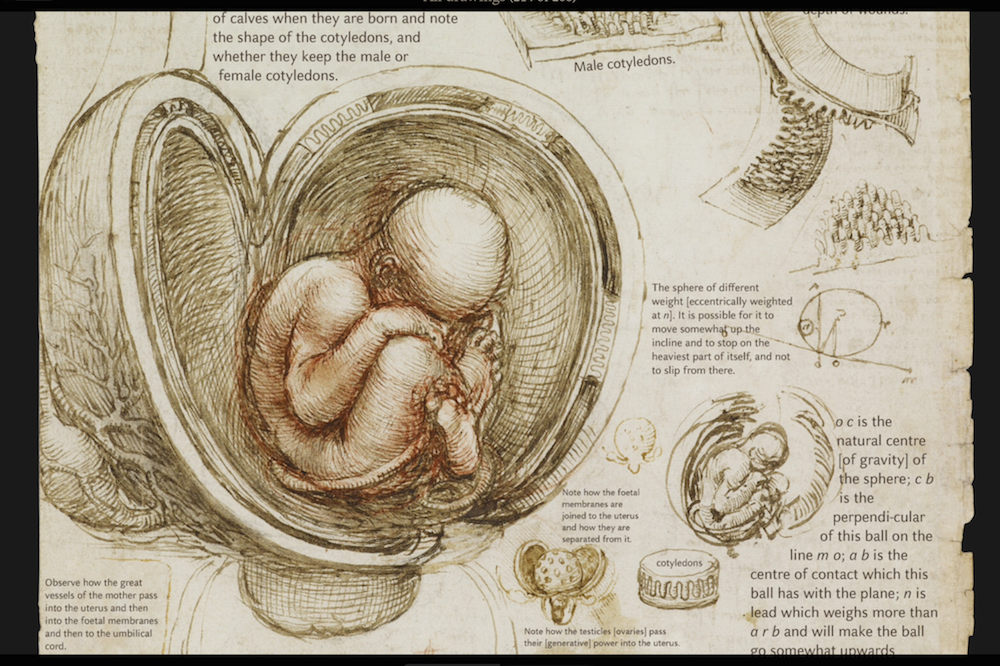

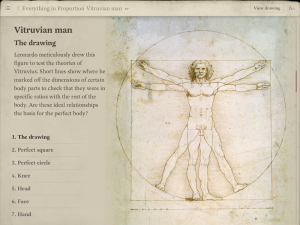

Of course, the drawings alone—among them Leonardo’s famous Vitruvian Man (the nude whose four outstretched arms and legs are inscribed within a square and circle, and owned by Venice’s Accademia Gallery)—are well worth the $13.99. The interactive capacity of digital publishing allows you to sort the images any way you choose and zoom in for the kind of close look you could never have gotten in person at the exhibition of the original drawings in England in 2013.

But the app also offers new insight into the copious and beautifully-formed notations with which Leonardo surrounded most of his drawings. For those who’d like to try reading Leonardo’s original Italian script written in his famous “mirror” (or backward) hand, the app provides a moveable box which, when held over the text, reverses the letters to their legible order. Another button translates all of the original text into English exactly where it originally appears on the page.

Yet what makes this application truly extraordinary, I think, and of interest to a far broader range of people than the students of art, medicine or science for which it seems essential, is the way in which Leonardo’s arduous and iconoclastic pursuit of knowledge is masterfully contextualized within a larger historical and cultural framework. And shown to inform, to this very day, the way we see our world.

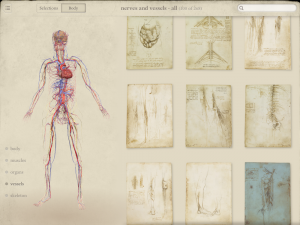

An interactive 3-dimensional computer model of the body (configurable by muscles, organs, vessels or skeleton) can be compared side-by-side to Leonardo’s own drawings to reveal exactly how they differ from or anticipate our contemporary knowledge of anatomy.

Other interactive 3D models show, for example, the beating heart in motion to demonstrate how blood flows through the heart and show exactly where Leonardo fell just short in his otherwise ground-breaking comprehension of the circulatory system.

In succinct and well-produced video clips, a surgeon, an anatomist, and two scholars present vivid discussions of Leonardo’s work from the viewpoint of their own expertise, acting as audio-visual supplements to Martin Clayton’s excellent introductory essay. And though we all know already that Leonardo was a genius, Clayton manages to foreground Leonardo’s humanity even as he explains the staggering discoveries Leonardo made in the least promising of circumstances and with the most basic tools.

In fact, Clayton’s account of how Leonardo came to undertake his anatomical studies, his original aims in doing them, and his methods, is nothing less than a dramatic, and inspiring, tale of intellectual curiosity, creativity, and dedication.

The study of anatomy through dissection had become an important pursuit by Leonardo’s time, but it was a messy, difficult and very confusing one. Not least of all because the great mass of information on the body in Leonardo’s day had been handed down from Greek and Roman times, and had more to do with metaphysical ideals than direct observation.

Adapting a technique he’d learned from the casting of bronze sculptures, Leonardo devised a method of injecting wax into the brain and heart to allow him to study chambers that otherwise would have collapsed. He was the first person ever to fix tissues in this way and the discoveries it allowed him to make were profound.

Among his many other “firsts,” Leonardo was the first to use multiple cross sections of a human body part to demonstrate how it was constructed—500 years before the CAT scan and MRI.

From architectural drawing, he borrowed the principles of elevation, plan and section, thereby developing a completely new approach to convey and conceptualize bodily forms in three dimensions.

And with each new discovery, each new technique, each new conceptual framework, Leonardo blazed a path away from the dogmatic, metaphysical system of knowledge he had inherited. In its place he developed one based on direct observation and helped lay the groundwork for scientific investigation.

At a time when the rigorous intellectual and scientific tradition left to us by Leonardo da Vinci is under attack both by fundamentalists of all sorts and massive corporate interests determined to co-opt its freedom of inquiry and its findings, when the pleasures of learning and the pursuit of knowledge are dismissed by commercial interests selling us (and our children) diversions they promise will be much more “fun”, this application serves as an important reminder of what we are in risk of losing.

True, none of us is likely to be another Leonardo da Vinci. But as an example of unflagging curiosity, of diligent observation and spectacular ingenuity, of a life-long pursuit of knowledge (he was in his 50s when he made his most important anatomical discoveries) and its many pleasures, he is an unparalleled role model.

All of which makes Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomy an ideal gift for all students. Whether those students will be graduating this spring, or whether they’re pursuing their own independent studies of human life, long after leaving school.

To see Touchpress’s full range of educational apps for iPad, visit: http://www.touchpress.com/

For more about living in Venice, visit Steven Varni’s blog: veneziablog.blogspot.com