Author’s note: This is the first installment of a serialized story that recounts my return to Italy and my grandfather’s journey to the U.S.

My grandparents poured into me all the Italy they couldn’t fit into their children. To others they spoke broken English, but to me, the first born grandchild, it was always their Italian, so I became the only one who could understand them. As they neared retirement, I was placed in their care on those rare occasions my parents weren’t around. I was their assistant who ran errands and extended their reach; my life became an internship into the ways they thought, the ways they felt, and the ways they got things done. Their ways of doing and being were always explained more through stories than detailed instructions.

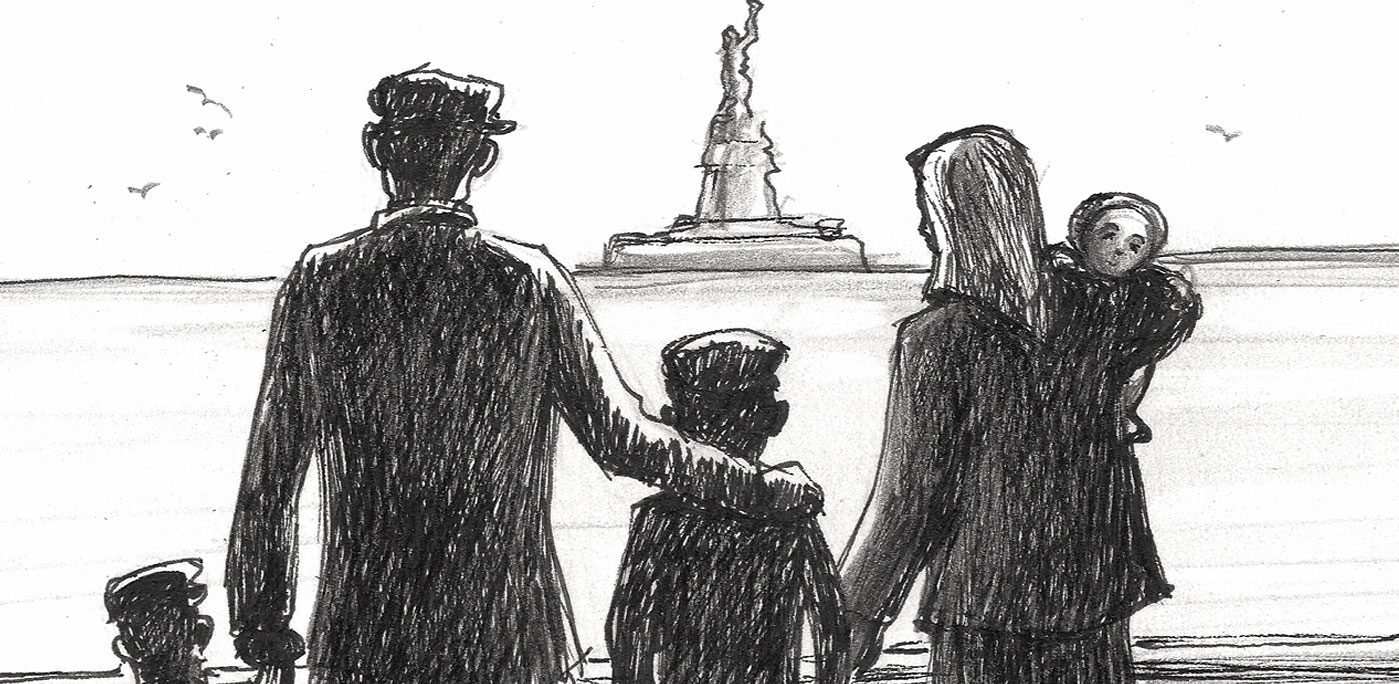

Grandpa was an immigrant who had never really arrived, one who carried the burlap sack of his past wherever he went, a weight that slowed him down in the fast moving, modern America of television and astronauts. Whatever Italy was to me in my youth came from him. He reflected a dual image of my Italian heritage: one of pride and one of embarrassment, images that constantly fought one another.

His broken English upset me, especially when he’d “speaka likea thisa” to me while I was with my non-Italian American friends, the ones he’d call “‘mericans.” His Italian, that strange tongue he’d use when spurred to a highly emotional point in an argument, while reminiscing with old friends, or when he didn’t want kids to understand what he was saying, always enchanted me. His language was only one way he conflicted with the America I was growing up in.

At breakfast he’d be hunched over a ceramic bowl filled with chunks ofstale bread, the kind Mrs. Rossi used to throw out to the birds in her back yard. I watched in disbelief as he poured hot coffee over the bread and then added scalded milk and sugar to the mixture. Then he’d eat it! While he ate, I gathered the courage to spill some cornflakes into my blue, Tupperware bowl and eat the American breakfast I had known from television. He offered me a taste of his concoction, which I rudely refused to his amusement. When I looked into his smile I lost the image I had had of him when I first saw him pour the coffee over the old bread. In that closeness I loved, but didn’t understand the immigrant.

Grandpa never used the products I thought were essential to American life. He bragged that he had never used shampoo or toothpaste and yet managed to keep a full head of beautiful hair and a mouth free of fillings. I was amazed, since by the age of ten I was already noticing dandruff and had visited the dentist more than he ever had his whole seventy years of life. He preferred to grow his own vegetables, while I’d be fascinated by the ease of picking unblemished, even-sized tomatoes and other produce neatly wrapped in plastic off supermarket shelves. I was frustrated by the hours spent with him in his garden, sweating to produce a few tomatoes and peppers, or following him through fields of forest preserves picking dandelion greens and poking puffballs down from trees.

Grandma was always the center of attention during the preparation of Sunday afternoon meals. She ruled the kitchen and hollered out orders to the women in our family. But my attention always turned to Grandpa while we ate. He fascinated me, using bread in fingers to gather sauce that slid off the spaghetti, tonguing neck bones until they were meatless and dry. He could make me forget I had food in front of me; he was a noisy eater, but the sounds he made were hardly noticeable amid the loud talk at the table. He rationed the salad of bitter dandelion greens by dancing around the table and dropping it onto plates, then would return to his seat, hug the huge wooden bowl with one arm and shovel forkfuls of greens into his mouth. When the storm of the meal had blown over, he would sit back and smoke an unfiltered cigarette, often with the lit end in his mouth. Magic!

Grandpa never learned to read or write and I would feel so important when he ordered me to read something for him. I was the American he could never be. I was proof that his hopes of “making it” in America had been fulfilled. Grandpa never told me why he had left Italy and rarely talked of his childhood. I guess he thought it was enough to be in America and that all that had come before no longer made any difference in his new home.

After he died, Sunday dinners were never the same. With him were buried many of the Italian traditions our family had followed at his lead. Without his influence, Italians became strangers in a collage of media images: spicy meatball eaters, Godfather gangsters and operatic buffoons. But he did leave me with a curiosity of what the “old country” was like.

One day, the year before he died, he and I were on a beach in southern California. Our family had traveled to my uncle Pasquale’s home after my father’s funeral. Grandpa sat on the sand, staring into the sun’s reflection off the waves. He said, “This beach, she like Monopoli” (a coastal town near Castellana Grotte in southeastern Italy, where he was born). “One day I’mma gonna go backa to Castellana.” He said nothing else the rest of the day. He was silent for hours, as though in a trance. It was a look I had never seen before and it frightened me. I covered him with sand and he sat there until the tide washed the sand away. He was burned quite badly, but it didn’t seem to bother him. He had been in Italy during those hours. It had been more than fifty years since he had seen the land he’d come from. Whenever I pictured Grandpa after he died, it was with the sad smile he had on his face that day on the beach.

As I turned my energies toward pursuing an education and the pleasures of being a teenager, the memories of Grandpa weakened. I often lost my family in my growing disenchantment with the American Way. In the late 1970s, I decided to get as far away from the family as possible. I planned a trip to Europe to visit friends in Denmark and Sweden. As I gathered addresses, I thought it might be interesting to visit Italy for a few days, if I had the time. Grandma had maintained only Christmas card contact with ” the other family” in Castellana Grotte. She had the address of Grandpa’s brother and I wrote him. By the time I left, I had not received a response and wondered if I should bother to stop in Castellana at all.

Nota dell’autore: questa è la prima parte di una storia in serie che racconta il mio ritorno in Italia e il viaggio di mio nonno negli U.S.

I miei nonni rovesciarono in me tutta l’Italia che non erano riusciti a far entrare nei loro figli. Agli altri parlavano un inglese stentato, ma con me, il primo nipote, sempre il loro italiano, quindi sono diventato l’unico che potesse capirli. Quando si avvicinarono alla pensione, io fui incaricato di badare a loro in quelle rare occasioni in cui i miei genitori non erano nei paraggi. Ero il loro assistente che gestiva le faccende e prolungava le loro possibilità: la mia vita era diventata un tirocinio nei modi in cui pensavano, nei modi in cui sentivano e nei modi in cui facevano le cose. I loro modi di fare e di essere sono stati sempre spiegati più attraverso storie che istruzioni dettagliate.

Il nonno era un immigrato che non era mai realmente arrivato, uno che portava il peso del suo passato ovunque andasse, un peso che lo rallentò nell’America moderna, in rapido movimento, della televisione e degli astronauti. Qualunque cosa di Italia io abbia avuto nella mia giovinezza, è venuta da lui. Lui rifletteva la doppia immagine del mio patrimonio italiano: una di orgoglio e una di imbarazzo, immagini che si combattevano costantemente l’una con l’altra.

Il suo inglese stentato mi sconvolgeva, specialmente quando mi diceva “parlare io a te”, mentre ero con i miei amici americani non italiani, quelli che chiamava “mericani”. Il suo italiano, quella strana lingua che usava quando era spinto ad un punto molto emozionante di una discussione, quando ricordava i vecchi amici, o quando non voleva che i bambini capissero quello che stava dicendo, mi ha sempre incantato. La sua lingua era solo uno dei modi in cui era in conflitto con l’America in cui stavo crescendo.

A colazione stava curvo su una ciotola in ceramica piena di pezzi di pane vecchio, quello che la signora Rossi usava per lanciarlo agli uccelli nel suo cortile. Guardavo con incredulità mentre versava il caffè caldo sopra il pane e poi aggiungeva il latte scaldato e lo zucchero alla miscela. Poi lo mangiava! Mentre mangiava, io raccoglievo il coraggio di far cadere i corn flakes nella mia ciotola blu Tupperware e poi di mangiare la prima colazione americana che avevo imparato dalla televisione. Mi offriva un assaggio del suo preparato, che io rifiutavo in modo rude per il suo divertimento. Quando guardavo nel suo sorriso perdevo l’immagine che avevo avuto di lui quando prima lo avevo visto versare il caffè sopra il pane vecchio. In quella vicinanza amavo, ma non capivo l’immigrato.

Il nonno non ha mai usato i prodotti che io pensavo fossero essenziali per la vita americana. Si vantava di non aver mai usato shampoo o dentifricio e tuttavia era riuscito a mantenere una testa piena di bei capelli e una bocca priva di otturazioni.

Ero sorpreso, poiché all’età di dieci anni avevo già notato la forfora e avevo fatto visita al dentista più di quanto non avesse mai fatto nei suoi settant’anni di vita.

Preferiva far crescere le sue verdure, mentre io ero affascinato dalla facilità di raccogliere pomodori immacolati e grandi e altri prodotti ordinatamente impacchettati nella plastica sugli scaffali del supermercato, ed ero frustrato dalle ore passate con lui nel suo giardino, sudando per produrre qualche pomodoro e peperone, o per seguirlo attraverso i campi delle riserve della foresta, per raccogliere tarassaco e far cadere giù i funghi dagli alberi.

La nonna era sempre il centro dell’attenzione durante la preparazione dei pasti della domenica pomeriggio. Governava la cucina e dava ordini alle donne della nostra famiglia.

Ma mentre mangiavamo, la mia attenzione si rivolgeva sempre al nonno. Mi affascinava per come usava il pane tra le dita per raccogliere la salsa che scivolava via dagli spaghetti, per come succhiava le ossa del collo fino a quando non erano senza carne e asciutte.

Poteva farmi dimenticare che avevo cibo davanti a me. Era un mangiatore rumoroso, ma i suoni che faceva erano quasi impercettibili nel vociare alto della tavola. Versava l’insalata di tarassaco verde amaro ballando intorno al tavolo e lasciandola cadere nei piatti, poi tornava al suo posto, abbracciava l’enorme ciotola di legno con un braccio e ammucchiava forchettate di verdure in bocca. Quando la tempesta del pasto era passata, si sedeva e fumava una sigaretta non filtrata, spesso con la punta illuminata in bocca. Magia!

Il nonno non ha mai imparato a leggere o scrivere e io mi sentivo così importante quando mi ordinava di leggere qualcosa per lui. Ero l’americano che non sarebbe mai potuto essere. Ero la prova che le sue speranze di “farcela” in America erano state soddisfatte. Il nonno non mi disse mai perché aveva lasciato l’Italia e raramente parlava della sua infanzia. Credo che pensasse che fosse abbastanza essere in America e che tutto quello che era stato prima non facesse alcuna differenza nella sua nuova casa.

Dopo la morte, le cene di domenica non furono più le stesse. Con lui furono sepolte molte delle tradizioni italiane che la nostra famiglia aveva seguito al suo comando. Senza la sua influenza, gli italiani sono diventati estranei in un collage di immagini mediatiche: mangiatori di polpette speziate, gangster di padrini e buffoni melodrammatici. Ma lui mi ha lasciato con la curiosità di quello che era il “vecchio paese”.

Un giorno, l’anno prima di morire, lui e io eravamo su una spiaggia nel sud California. La nostra famiglia era andata a casa di mio zio Pasquale dopo il funerale di mio padre. Il nonno si era seduto sulla sabbia, a fissare il riflesso del sole sulle onde. Aveva detto: “Questa spiaggia è come Monopoli” (una città costiera vicino a Castellana Grotte nell’Italia sudorientale dove è nato). “Un giorno tornerò a Castellana.” Non disse altro per il resto della giornata. Rimase in silenzio per ore, come se fosse in trance. Era uno sguardo che non avevo mai visto prima e mi spaventò. Lo coprii di sabbia e lui rimase lì fino a che la marea non gli lavò via la sabbia. Si scottò molto ma non sembrò preoccuparsene. Era stato in Italia durante quelle ore. Erano passati più di cinquant’anni da quando aveva visto la terra da cui proveniva. Ogni volta che ho immaginato il nonno dopo la sua morte, era con il sorriso triste che aveva in faccia quel giorno in spiaggia.

Mentre dirottavo le mie energie verso la ricerca di un’istruzione e i piaceri di essere adolescente, i ricordi del nonno si indebolirono. Ho spesso perso la mia famiglia nel mio crescente disincanto sulla via americana. Alla fine degli anni ’70 decisi di stare lontano dalla famiglia il più possibile. Programmai un viaggio in Europa per visitare amici in Danimarca e in Svezia. Avendo raccolto indirizzi, pensai che poteva essere interessante visitare l’Italia per qualche giorno, se avessi avuto il tempo. La nonna aveva mantenuto i contatti solo tramite i biglietti di Natale con “l’altra famiglia” a Castellana Grotte. Aveva l’indirizzo del fratello del nonno e gli scrissi. Quando partii, non avevo ricevuto una risposta e mi chiesi se avrei dovuto preoccuparmi di fermarmi a Castellana.