Giuseppe “Joe” Desimone was a bear of a man, 6 foot 2 inches tall, 300 pounds. He arrived in America in 1897 from Naples at the age of 18 with 50 cents in his pocket. He worked first as a swine farmer in Rhode Island, then made the journey west to Seattle.

At this point, his life might have taken the usual path for an Italian immigrant, finding work as a manual laborer, miner or tenant farmer, except that Desimone was a most unusual man. It’s true he started out as a produce farmer in south Seattle, but he eventually bought the market—Pike Place Market, that is, one of Seattle’s most beloved icons. And, even more unexpected, this immigrant from the south of Italy played a pivotal role in keeping the Boeing Company in Seattle during World War II.

By the early 1900s, Italians, Germans, Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos owned or tended nearly half the farms in King County. Land was plentiful and cheap. Seattle’s temperate climate, fertile soil and frequent rains were ideal for growing crops.

At the time, farmers could not sell directly to consumers; instead, they had to sell to commission houses who acted as middlemen. The farmers found themselves at the mercy of commission agents who often resorted to unfair, even shady, practices to increase their profits. Farmers barely broke even and customers complained of price gouging.

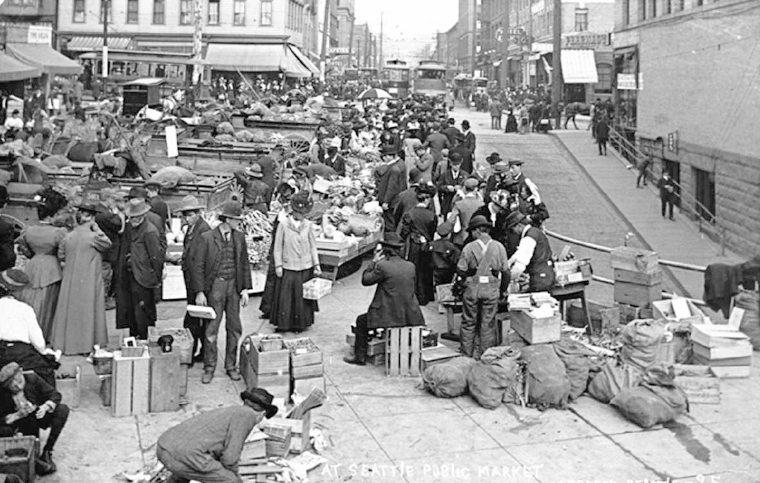

At last, the city passed an ordinance that established a farmers market at Pike Place. On the first Market Day, August 17, 1907, a handful of farmers trucked their produce in and began to sell it off their own wagons and carts. By 11 a.m., they were sold out, turning away scores of customers.

In a book on the history of Pike Place Market, authors Alice Shorett and Murray Morgan quoted Italian farmer Antonio Ditore, as he described the chaos during that first day at the market. “The people come a runnin’ and I give some things without a paper bag. And they was glad to get it. And now I think in an hour there, I make seven, eight dollars.”

Word spread fast. Within a week, there were 70 wagons parked along Pike Place, each filled to overflowing with farm produce. Real estate developer Frank Goodwin, just back from a successful gold-mining venture in the Klondike, saw the investment potential and decided to build permanent arcades on the site.

By December 1907, the first Pike Place Market building opened. Japanese farmers operated about 75 percent of the stalls; the Italians ran virtually all the rest. A 1910 report noted that Italians with even modest acreage could sell about $5,000 worth of produce annually.

Joe Desimone was not only a produce farmer, but a shrewd businessman as well. As his coffers grew, he invested in real estate rather than stocks or speculation. Over the next several decades, he continued to buy land, draining the Duwamish swamplands, a move that gave him some of the most fertile farmland in the region. Soon he had amassed a fortune.

In 1941, he went from selling his produce at Pike Place Market to becoming its president and majority stockholder. He kept maintenance costs to a minimum so he could rent the stalls to farmers at low rates. This tactic helped the market survive the war years but it also allowed the arcades to decline over time. The maze of aging buildings was slated for demolition until a “Save the Market” campaign was overwhelmingly approved by voters in 1971, saving the day.

Desimone retained ownership of Pike Place Market until his death in 1946 when his son took over. In 1974, the family sold the public market to the city of Seattle. The Desimone Bridge, which can still be seen at the market, is a reminder of the family’s ties to that enterprise. But Desimone’s impact on Seattle was even more far-reaching.

In the mid-1930s, Boeing realized it would need to expand its operations if it were to compete for lucrative defense contracts. But the company felt hemmed in at its current location and land was at a premium.

When Desimone heard that Boeing might move out of town, he made Boeing an offer it could not refuse. He sold the company several acres of his own land south of downtown Seattle. The price: One dollar.

Boeing took the deal and in 1936, Plant No. 2 was built on the site. Thousands of people worked in the 60,000-square-foot plant, famous for its production line of B-17 bombers known as “Flying Fortresses.” Plant No. 2 was so critical to the war effort that Boeing camouflaged its roof with fake streets and houses made of burlap and plywood, rendering the plant nearly invisible from the air.

Whether keeping market stalls open at Pike Place Market or ensuring that Boeing could expand its wartime production efforts, Desimone’s impact on Seattle was formidable. Thanks to his hard work, business savvy and desire to give back to his adopted country, this “giant” from Naples helped shape Seattle’s history for decades to come.