We all love – or should love – books. They keep the essence of culture and help passing it on to the next generations. They tell stories: invented, when they’re novels, of how events took place and why, when about history, of discoveries and how the world works, when related to science.

Each and every book, though, also tells another type of story to those attentive enough and with a trained eye: they keep, within and on their pages, the secret of how they came to be. This is especially true for ancient manuscripts, where the type of script, the ink, and the characteristics of the vellum used can tell us where the text was written, when and even show signs of corrections. Analyzing different manuscripts of the same text can bring a paleographer to understand and compile the original version of the text itself, thus enhancing our knowledge of its content and the reasons behind its composition.

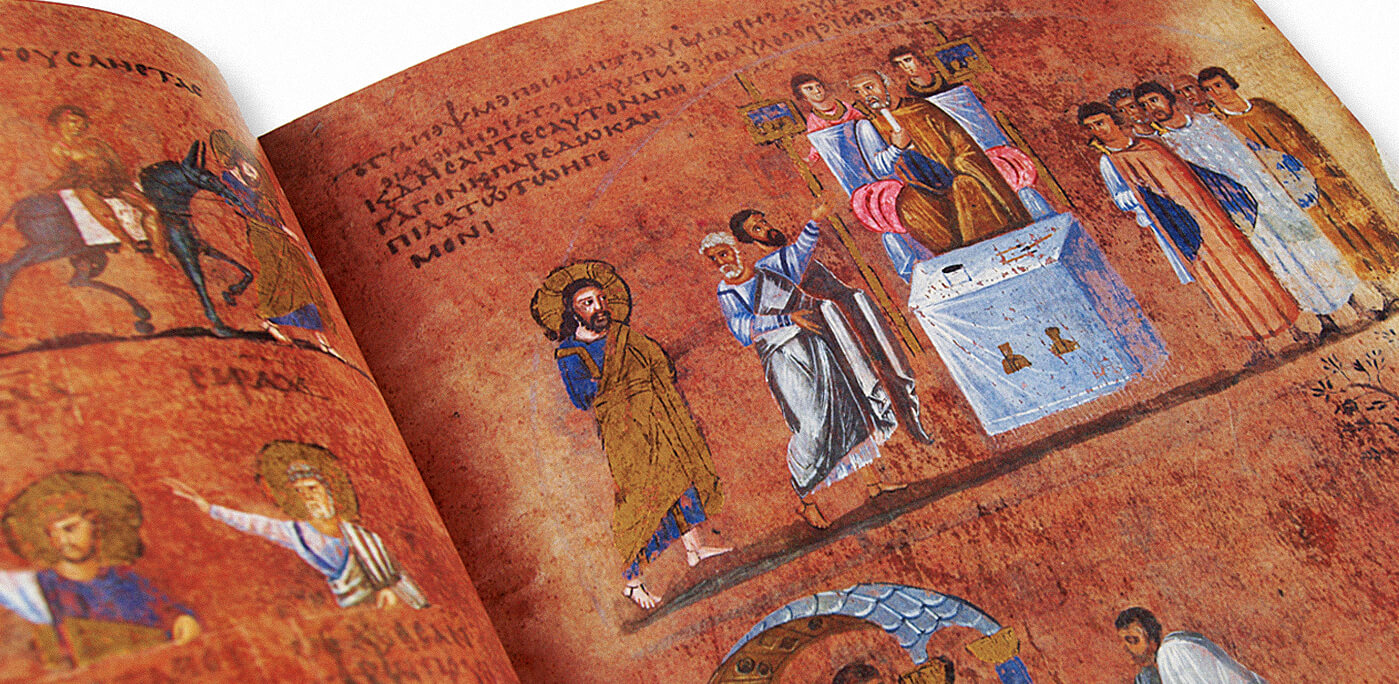

The Codex Purpureus Rossanensis is one of the many beautiful manuscripts Italy has been holding within the dark shelves of its historical libraries for centuries, yet it has something different from the others: it’s one of the earliest complete versions of the Gospel of Matthew and Mark extant (only a handful of verses of the latter are missing), it was written on a peculiar type of parchment with a distinctive reddish hue (hence the name “purpureus”) and, last but not least, it comes with an amazingly intricate series of drawings, which makes it one of the most amazing examples of illuminated work of the Late Antique period.

It’s this last characteristic that makes it more interesting: if it’s true that a large amount of Late Antique and Medieval manuscripts are illuminated, the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis’ wealth of illustrations makes it more of a fully illustrated text, rather than simply miniated.

Originally formed by 400 sheets, only 188 survive today, containing 15 large illuminations illustrating the events of the Gospels. Entirely written in Greek, the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis has been, very likely, composed around the 6th century AD and it’s probably Byzantine in origin. Through careful comparisons made with other artefacts of the same periods, experts feel it may have been produced in Syria, possibly in Antioch, and may have reached Rossano, in Calabria, around the 7th century AD, when a large wave of migrating Eastern Greek monks hailed to the West after the first Iconoclasm.

Discovered in 1846, but fully studied only in 1879 by a German team, the beautiful manuscript has come to the attention of the wider public during the Summer, when it was returned to Rossano after a four year long restoration. In 2012, the local archbishop, monsignor Giuseppe Satriano, entrusted it to an equipe of experts who, through a delicate, long and complex work, restored damages to the parchment and strengthened its binding. Thanks to their work, something more about the history itself of the manuscript resurfaced: confirmed were its age and origin, and further analysis proved the codex had been damaged several times, dismembered and very likely survived a fire. Detrimental has been also a 1917 restoration work carried out by Nestore Leoni who, the head of the Icrcpal Restoration Laboratory Lucilla Nuccettelli says, “carried it out well, but was betrayed by the restoration techniques of those years, which have long proven highly damaging.”

With its fifteen centuries of life and the beauty and complexity of its illustrations, its restorers say, the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis should be considered the first illustrated text of our history.

In spite of the extensive works made, the Purpureus Rossanensis remains an extremely fragile artefact: it needs to be maintained constantly at a temperature between 18 and 20 degrees Celsius and away from dust, insects and human hands. When open, it has to lay on two wedges and its pages can be turned only once per year.

Today, this beautiful example of art can be seen in the Diocesan Museum of Rossano, where it’s kept in a specially designed display cabinet. On the 9th of October 2015, the International UNESCO Committee inscribed it in its “Memory of the World” list, stating that the manuscript “is known worldwide for the peculiar reddish color of its pages, written in silver and gold inks and has a series of 15 illuminations, illustrating the life and teaching of Christ. The superb miniatures make it one of the oldest illuminated manuscripts of the New Testament.”