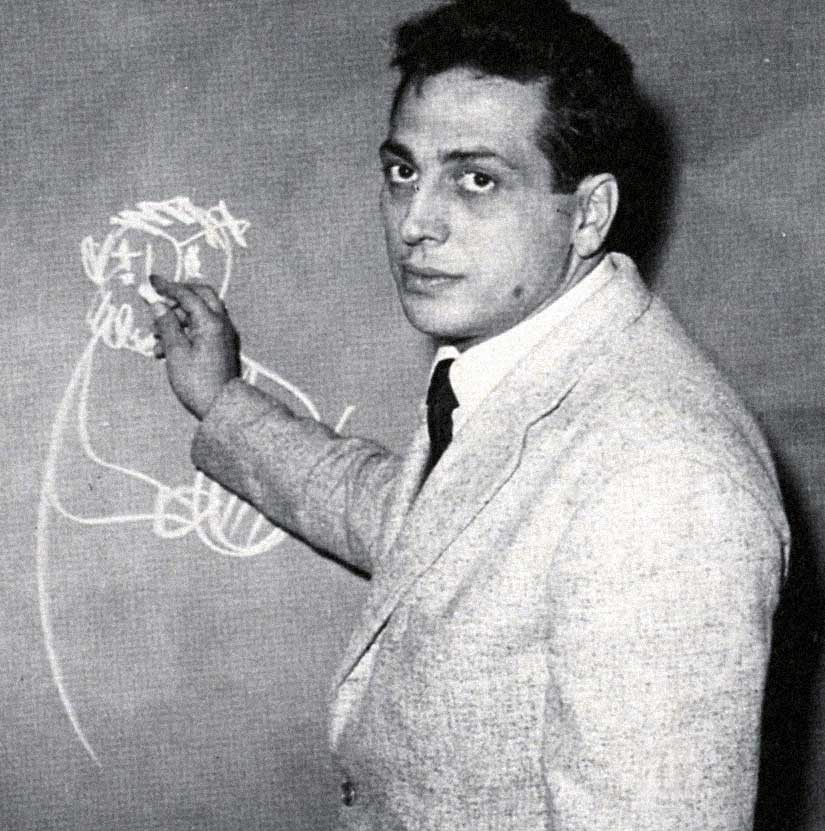

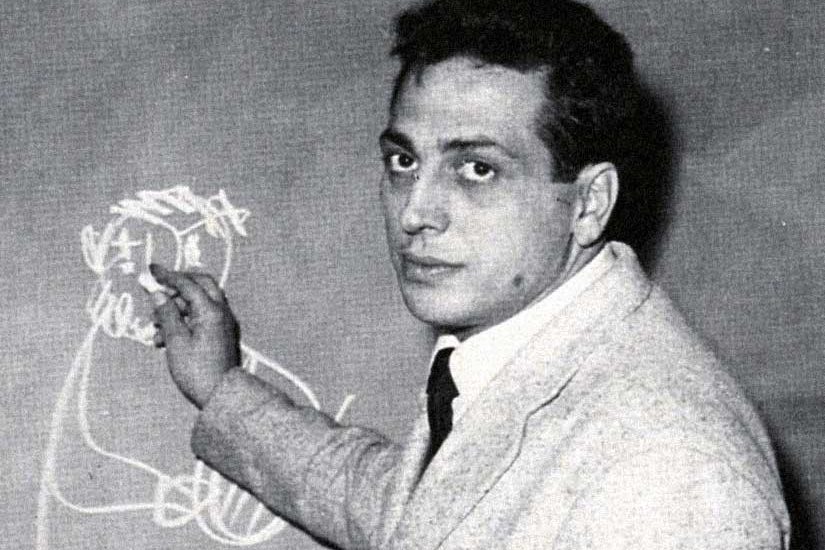

Between 1960 and 1968 RAI aired Non è Mai Troppo Tardi (It is Never too Late), a show aimed at fighting illiteracy, as more than 10% of the Italian Population was still, at the beginning of the 1960s, unable to read and write. Alberto Manzi was a pedagogue, a writer, and, above all, an elementary school teacher: he was the one who, with success, hosted the show, teaching lessons that went well beyond the alphabet and that are still extraordinarily relevant today.

Right in the middle of the Covid-19 emergency, with all our schools closed and distance learning being the status quo for all students, at all levels, it became clear we are in front of a never-before-encountered challenge. Many feel lost, and navigate the labyrinth of the online world in the hope this is going to be nothing more than a parenthesis before a swift return to normality takes place. Others simply apply to new context habits they already have. Others still fear this experience may change forever the school system and the way we teach and we learn. Maestro Manzi’s name and his TV lessons are evoked almost on a daily basis, proposed as an inspiration and example of methods and solutions to apply. Without a doubt, Manzi still has a lot to teach and his didactic vision, based on active participation and discovery, should be of guidance to us. But who was, truly, il Maestro Manzi, what does he (or does he not) have to do with distance learning and how can he help us face the challenges of our time?

The type of distance learning imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic is rooted, above all, in the necessity to maintain social distancing. Teachers and pupils, professors and students, are no longer allowed to be near one another. The type of school we know, at the heart of so much of our socializing, relationships, and, of course, learning, has all of a sudden become a dangerous place where the virus, our invisible enemy, threatens the day-to-day nature of our connections. Distance learning takes the place of in-class learning, becoming a parallel universe to it. It is a type of learning where the challenge to create continuous stimuli, to open people’s minds, and rise curiosity for learning continues, but without some fundamental aspects of the process, those that do not simply involve the mind, but also the physicality of movements and social interaction, the senses, the meeting of living bodies that move and explore. Distance learning no longer supports these avenues — which we know so well and love so much — so we are forced to explore other ways.

Let’s go back to 1960, the year when Maestro Manzi began hosting his Non è Mai Troppo Tardi show. Here, the type of distance learning we find is profoundly different from that of today, not only because of the instruments used (more than half a century makes a big difference), but also because of methods and aims. Television was not a simple technological device, but an educational system, with a precise formative mission. Manzi’s show, to which he contributed also as a content creator, was supported by a precise and well-structured network of “on-the-field” interventions that went well beyond the TV show itself: learning hubs popped up around the country, teachers and TVs were sent to every region, exercise books were created and distributed to integrate TV lessons and to stimulate learners further. The goal was that of educating a large number of people who, otherwise, would have never had the opportunity to go to school in a traditional way. It was, in other words, an institutional answer to the educational needs of a country still profoundly scarred by social inequality and economic problems.

While Covid-19 distance learning must, through a never-seen-before mechanism, become a didactic instrument for the whole of society, an orphan in its entirety of the possibility to interact, Maestro Manzi’s distance learning was addressed to a specific stratum of our population: the excluded, those who, for a reason or the other, were on the margins of society. Reaching where in-class learning could not reach, Non è Mai Troppo Tardi built bridges for those who needed it the most.

Today’s distance learning imposes (but fails to guarantee) equal use for all of a computer or a tablet, equal access to the internet, and to adequate spaces to learn online, thus boldly defining the social and digital gap present in the nation. Alberto Manzi’s distance learning, though, used to do the opposite, because it filled that gap offering the most fragile in our society the opportunity to redeem themselves through literacy.

What can we, therefore, learn from a fifty-year-old experience, one so different in means, objectives, and rationale? If we look at it from the right perspective, we can learn a lot; yet we must resist the temptation to think about Maestro Manzi only as a precursor of distance learning. On the other hand, if we look at him as the educator who inspired thousand of Italians to learn how to read and write thanks to his respect, his patience and passion, his TV lessons will not only become an example of advanced multimedia techniques, but also guidance and representation of those humanistic values that, today more ever, have become essential. All the 484 episodes of Non è Mai Troppo Tardi are inspired by the fundamental principles of that Movimento di Cooperazione Educativa(Movement of Educational Cooperation) Alberto Manzi embraced: respect for the individual, social solidarity, the importance of asking questions, the development of critical thought and responsibility. These are all essential tenets for the cultural and intellectual formation of modern active citizenry.

Although in his TV lessons, Manzi intuited a series of principles that were to become pivotal for today’s online teaching, such as using images, videos, and drawings, or personalizing lessons and dividing them into sections, the fundamental value of his work is not in his technical abilities (or, certainly, not only in this), but rather in a clear and visible learning path based on empathy, respect for the individual and a continuous search for meanings that transcended the curriculum and the alphabet. Let us go back to the 14th of January 1966: on that day, Maestro Manzi’s show was on. From the screen, Manzi greets his audience, chats with them about anything and everything, and creates the best condition to support learning: trust. Even if the lessons are created for adult illiterates, a large number of pre-school children learn how to read and write thanks to his TV classes, as the thousands of letters they send him to declare. “We are here to learn and know better the world and ourselves. This is what, in the end, reading and writing are useful for.” That’s how Manzi would start each lesson, making clear how reading and writing are just instruments. Through questions and challenges, il Maestro stimulates his public’s interest and its curiosity, with the aim of keeping what he calls “cognitive tension” always working. After writing on his large white notebook (the TV equivalent of the iconic blackboard) words that his students still cannot read (pino, mare, nave, casa), il Maestro looks straight into the camera, into people’s homes, and says: “What did I just write?” It seems almost apologetic when he admits he knows his friends at home cannot read those words. “That’s why — he says reassuringly — we are here together. To overcome this problem.”

With only a few, precise black charcoal strokes on white paper, Manzi then brings to life a marine landscape, evoking images his audience knows well: a pine with the sea in the background, a ship sailing on it, and, finally, a house on the shores. “Here you could read them (the words). Why?” And so, he explains simply and clearly that images are symbols and that’s why people at home can understand them. Other signs, Manzi continues, like the graphemes that create the words pino, mare, nave and casa are symbols, too, that allow us to communicate and to read what other people wrote. When he introduces his viewers to the concepts of signifier and signified, our TV teacher brings language learning to a higher cognitive level. When he brings their attention to the role of reading as an instrument to understand reality, he tells them they are part of Non è Mai Troppo Tardi’s didactic process, not simple recipients of it. The following 30 minutes, on that Thursday, 14th of January 1960, and the lessons on the following days, were to be filled with ideas, activities, guests, day-to-day inspirations so that his public would not forget how reading and writing are fundamental part of their lives, but also that they have to work hard at it.

Alberto Manzi’s TV lessons were more than a mere attempt to alphabetize 1960s Italy. They were meetings livened by questions, by pauses to be filled and things to be guessed, by poems to reflect upon and values to learn and make one’s own. By rising the cultural expectations of his viewers and in proposing a path steeped in empathy and shared values, Alberto Manzi stated that neither writing nor reading could exist apart from the centrality of the Human Being; he said that literacy and culture could be built only around the idea of community, by looking more carefully into ourselves and at others. This is the lesson we truly need when thinking about the type of distance learning Covid-19 has been forcing us to experience. We need to set ourselves finally apart from a type of learning that focuses on the means but not on the aims. By sitting in front of a computer or a TV we don’t learn anything and it isn’t by simply pushing content through a screen that we teach something. We must keep on asking ourselves about the values guiding us, about where they will lead us, and about how (and whether) the pedagogical processes, means, and methods we choose are — or are not — coherent with them. Let us take, then, Alberto Manzi as an example, but let us embrace his message fully, especially when he talks of honesty, participation, responsibility, and respect.

Tra il 1960 e il 1968 la RAI mandò in onda Non è mai troppo tardi, una trasmissione avente lo scopo di combattere l’analfabetismo che all’inizio degli anni ’60 superava il 10%. Alberto Manzi, pedagogo, scrittore, ma soprattutto maestro di scuola elementare, condusse il programma con successo, insegnando lezioni che andavano ben oltre l’alfabeto e che rimangono a tutt’oggi di grande attualità.

Nel pieno dell’emergenza da COVID-19 con scuole chiuse e didattica a distanza per ogni scuola di ordine e grado, è chiaro a tutti che stiamo affrontando una sfida senza precedenti. I più si avventurano disorientati nel labirinto del digitale sperando sia solo una parantesi in attesa del ritorno alla normalità. Altri attingono ad abitudini già sperimentate consolidando e affinando usi e conoscenze di un mezzo già noto. Per altri ancora sopravviene la paura che l’esperienza possa trasformare per sempre la scuola e il modo di imparare e insegnare. Non passa giorno che il nome del maestro Manzi e le sue lezioni televisive non siano evocati come possibile ispirazione di metodi e soluzioni. È indubbio che Manzi abbia, a tutt’oggi una quantità di lezioni da insegnarci e che la sua visione educativa improntata alla partecipazione e alla scoperta non possa che continuare a guidarci. Ma chi era veramente il maestro Manzi e che cos’ha (o non ha) a che fare con la didattica a distanza che possa aiutarci oggi ad affrontare le sfide del nostro tempo?

La didattica a distanza con cui il COVID-19 ci impone oggi di confrontarci nasce, in primo luogo, dalla necessità della distanza sociale. Maestri e bambini, studenti e docenti non possono più stare vicini. La scuola che conosciamo, opportunità di relazione e socialità – oltre che di apprendimento – è diventata, improvvisamente, un luogo di pericolo dove il virus, nemico invisibile, minaccia anche la quotidianità dei rapporti. La didattica in remoto deve così sostituirsi a quella in presenza, proponendosi quasi come un mondo parallelo. È una didattica a cui è posta la sfida di continuare a stimolare, aprire menti e suscitare la curiosità dell’apprendimento, in assenza di requisiti fondamentali che coinvolgano il corpo oltre che la mente. La fisicità dei movimenti e delle relazioni, il coinvolgimento dei sensi, l’incontro tra corpi vivi che si muovono ed esplorano non supportano più l’apprendimento nei modi a noi noti e siamo forzati ad esplorare altri percorsi.

Facciamo ora un passo indietro al 1960, anno in cui il maestro Manzi iniziò a condurre la trasmissione Non è mai troppo tardi. Troviamo qui una didattica a distanza profondamente diversa non solo negli strumenti (più di mezzo secolo fa una grande differenza) ma nei modi e negli scopi. La televisione non era semplice strumento di trasmissione, bensì sistema educativo con una precisa missione formativa. Il programma a cui Manzi contribuì con il suo ruolo di creatore di contenuti, conduttore e maestro, era supportato da una precisa e studiata rete di interventi che andavano ben oltre le sue apparizioni televisive: punti di ascolto periferici, maestri e apparecchi televisivi inviati sul posto, eserciziari che integravano le lezioni televisive così che gli alunni potessero ottimizzarne gli stimoli. L’obiettivo era raggiungere ed educare una moltitudine di persone che non avrebbero diversamente avuto accesso all’istruzione attraverso la didattica tradizionale. Si assisteva ad una risposta istituzionale ai bisogni educativi di un paese ancora profondamente segnato dall’ineguaglianza sociale e dai problemi economici.

Se la didattica a distanza del COVID-19 deve, in un meccanismo senza precedenti, farsi strumento educativo per un’intera società a cui è stata sottratta ogni forma di interazione fisica e deve sostituirsi alla didattica in presenza per tutti gli alunni, la didattica a distanza operata dal maestro Manzi si rivolgeva a uno strato preciso della popolazione: gli esclusi, coloro che si ritrovavano, per una ragione o per un’altra ai margini della società. Integrando la didattica in presenza che da sola non sarebbe bastata a raggiungere tutti, Non è mai troppo tardi gettava dei ponti a coloro che più ne avevano bisogno. Se la didattica a distanza odierna, attraverso la richiesta (ma non la garanzia) dell’uso di un computer o un tablet, dell’accesso alla rete e della disponibilità di spazi adeguati da cui connettersi, mette in evidenza il divario digitale e sociale tra gli apprendenti, la didattica a distanza in cui operava Alberto Manzi faceva esattamente l’opposto, colmando quel divario, e offrendo l’opportunità ai soggetti più fragili della società di riscattarsi attraverso l’alfabetizzazione.

Cos’abbiamo dunque da imparare oggi da un’esperienza di più di cinquant’anni fa che era così diversa nei mezzi, negli obiettivi e nei presupposti? Se ci poniamo nella giusta prospettiva di osservazione, gli insegnamenti sono molti e importanti. Dobbiamo però resistere alla tentazione di pensare al maestro Manzi solo come a un precursore dell’istruzione a distanza. Se guardiamo a lui come all’educatore che ha ispirato con rispetto, pazienza e passione migliaia di italiani ad apprendere gli strumenti della lettura e della scrittura, le sue lezioni televisive ci appariranno non solo come un esempio di tecniche multimediali all’avanguardia bensì come una guida e un esempio di valori umanistici che, oggi più che mai sono irrinunciabili.

I 484 episodi televisivi di Non è mai troppo tardi non si discostano infatti nella loro didattica ispiratrice dai principi fondamentali del Movimento di Cooperazione Educativa a cui Alberto Manzi era molto vicino: il rispetto della persona, la solidarietà sociale, il valore del porre domande, lo sviluppo dello spirito critico e del senso di responsabilità. Tutti presupposti fondamentali per quella che potremmo definire oggi la formazione della cittadinanza attiva.

Sebbene Manzi abbia dimostrato nelle sue lezioni televisive di aver intuito una serie di principi propri dell’insegnamento online facendo uso di immagini, video e disegni, segmentando le sue lezioni e personalizzandole, il valore fondamentale del suo lavoro non sta nelle sue abilità tecniche (o certamente non solo) ma nel percorso chiaro e visibile che passa attraverso l’empatia, il rispetto dell’essere umano, e la ricerca di significati che vadano oltre i contenuti e le lettere dell’alfabeto. Torniamo indietro al 14 gennaio del 1966, uno dei giorni di messa in onda della trasmissione che, grazie alla presenza amichevole e alla gentilezza del maestro televisivo, era diventato un appuntamento regolare nella giornata di molti italiani. Dallo schermo, Manzi saluta i suoi telespettatori, chiacchiera con loro del più e del meno e crea la migliore condizione per l’apprendimento: la fiducia. Sebbene la trasmissione sia rivolta a un pubblico di analfabeti, moltissimi bambini in età prescolare godono delle sue lezioni e, a detta delle loro migliaia di lettere, imparano a leggere e scrivere insieme lui. “Siamo qui per imparare a conoscere meglio il mondo e noi stessi. È a questo, dopotutto che serve leggere e scrivere”. Così Manzi inizia la sua lezione, chiarendo sin da subito che leggere e scrivere sono solo strumenti. Attraverso domande e sfide a comprendere la realtà, il maestro solletica l’attenzione del pubblico, la sua curiosità, tenendo sempre attiva quella che lui amerà chiamare tensione cognitiva. Dopo aver tracciato sul suo grande blocco bianco (l’equivalente televisivo dell’irrinunciabile lavagna) parole che il pubblico non è ancora in grado di decifrare [pino, mare, nave, casa], il maestro guardando dritto nelle case degli italiani chiede: “Cosa ho scritto?”. Il tono è quasi di scusa quando ammette di essere consapevole che ancora gli amici a casa non sanno leggere le sue parole. “E` proprio per questo [dice con tono rassicurante] che siamo qui insieme. Per superare questa difficoltà”.

Con pochi, abili tratti di carboncino nero su foglio bianco, Manzi darà vita a un paesaggio marino evocando immagini ben note al pubblico a casa: un pino sullo sfondo del mare, una nave in lontananza, e infine una casa sulla riva. “Voi qui avete potuto leggerle [le parole], perché?”. Spiega con semplicità e chiarezza che le immagini altro non sono che simboli, e questa è la ragione per cui a casa gli spettatori hanno potuto dare loro un senso. Altri segni, continua Alberto Manzi, come i grafemi che formano le parole pino, mare, nave, casa sono simboli a loro volta, che ci permettono di comunicare tra di noi, e di leggere quello che altri hanno scritto. Nel parlare al suo pubblico della corrispondenza tra il significante e il significato, il maestro televisivo porta l’insegnamento dell’abecedario a un più alto livello cognitivo. Dirigendo l’attenzione degli spettatori sul ruolo della lettura come mezzo per la comprensione della realtà, li rende partecipi del progetto educativo di Non è mai troppo tardi, e non suoi semplici destinatari. I trenta minuti di lezione di giovedì 14 gennaio 1966 e dei giorni che seguiranno sono pieni di idee, attività, ospiti in studio, ispirazioni attinte al quotidiano così da non far mai dimenticare al suo pubblico che la lettura e la scrittura sono una parte fondamentale della vita, ma che ognuno deve metterci del proprio.

Le lezioni televisive di Alberto Manzi erano molto di più del tentativo di alfabetizzare l’Italia degli anni Sessanta. Erano incontri costellati di domande, di pause da riempire, di tratti abbozzati da indovinare, di poesie su cui riflettere, valori da riconoscere e in cui riconoscersi. Nell’elevare le aspettative culturali dei suoi telespettatori, nel proporre un percorso fatto di empatia e valori condivisi, Alberto Manzi affermava che non c’è lettura e scrittura che possa prescindere dalla centralità dell’essere umano; che un’alfabetizzazione, e quindi una cultura, si costruiscono soprattutto sull’idea di comunità, sviluppando uno sguardo più attento su noi stessi e sugli altri.

È questa la lezione di cui abbiamo bisogno quando pensiamo alla didattica a distanza che l’emergenza del COVID-19 oggi ci impone. Abbiamo bisogno di prendere distanza da una didattica che dimentica gli obiettivi concentrandosi sui mezzi. Non è stando seduti davanti a un computer o a un televisore che impariamo qualcosa; non è veicolando contenuti attraverso quel computer o quel televisore che insegniamo qualcosa. Dobbiamo continuare ad interrogarci sui valori che ci guidano, sul dove ci conducono e su come i processi, mezzi e i modi educativi che adottiamo sono (o non sono) coerenti con i nostri valori. Prendiamo dunque ad esempio Alberto Manzi ma ascoltiamolo fino in fondo quando ci parla di onestà, partecipazione, responsabilità e rispetto.