From Thanksgiving to Christmas, the leap feels almost instantaneous. Time seems to race faster with every passing year, and December feels shorter and shorter. A hundred tasks to juggle, a hundred thoughts swirling. Mornings disappear in a blur, afternoons vanish just as quickly, and days that dragged in November now sprint toward the most dazzling midnight of the year. Frenetic days filled with twinkling lights, home decorations, and festive shop windows blend into the daily grind—gift lists to tick off, last-minute office deadlines to meet—until suddenly, the year is ending.

A flood of thoughts, a flood of memories. How much heavier must the anticipation of the holidays have been for Italian emigrants who crossed the ocean without looking back, never returning after that first, interminable voyage that opened a world of promise and unforeseen challenges. How many wished they could go back, undo their departure, or at least make the occasional journey home, to the place where aging parents, childhood friends, and familiar landscapes waited. Where the house, the village square, the church, and a lifetime of toil were inseparable from their memories.

The early years in America were far from easy. Grueling work in mines, laying railroad tracks, unloading crates of fish with frozen hands in the morning, stamping tin cans in factories, arranging apples and zucchinis at market stalls with a forced smile for every customer while their bodies ached with exhaustion. Bosses barking orders in a language that never felt like their own, raising shop shutters surrounded by unfamiliar faces and wary stares.

Christmas came without the scent of freshly baked bread on the kitchen table or the simple desserts rationed out during the holidays, rich with flavors that carried them back to another time. Without those rough, weathered walls, always seeming ancient, and the sparse furniture shared by too many people. In the village, Christmas meant mass in the cold, where candlelight warmed hearts, eyes met in quiet humility, and prayers were offered for a new year generous to the fields.

Tomorrow, I’ll send some money home—to help Mama buy a trousseau for little Maria, medicine for Grandma Antonia, and to make Papa proud so he can boast about his son in America, where everyone seems to thrive, and life is nothing like here, in this poor village where dreams wither and survival is earned in sweat. If only they knew the reality: the hardship, the exploitation, the lump in the throat, the coins that don’t rain from the sky, and the weight of loneliness under this gray, foreign sky, colder than the one at home, where solitude was unknown.

And yet, even in that little village, within those walls steeped in time and simplicity, Christmas was no longer the same. In that now quieter house, eyes often lingered on an empty chair, mornings spent at the window waiting for a postman who never came, and that one letter, carefully tucked in the drawer, read a thousand times over, each reading stirring new thoughts and old memories. It weighed heavily on the heart as warm tears silently fell. Nothing had been the same since that piece of their heart left, taking their youth and hope with them. Even with daily chores as the only allowed distraction, thoughts always returned to that faraway child. A ladle of soup at the bottom of the pot was always set aside for him. Was he doing well? Did he live in a clean, spacious house? Did the bright city lights illuminate endless crowded streets like the stars filled the warm summer skies at home?

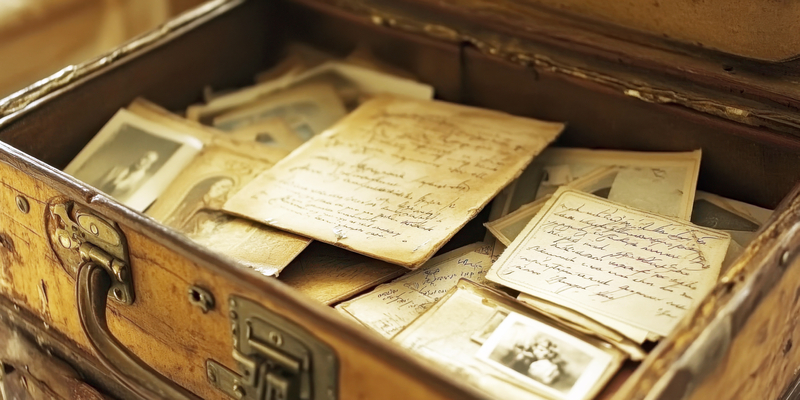

Harvest after harvest, winter after winter. Weddings, births, aches, and more springs. The years slipped by. Some returned with news from faraway lands. The village grew older and emptier, while the skyscrapers multiplied across the ocean. So much had changed—friends lost, lives lived. Every Christmas brought its prayers and hopes, each holiday hiding, amidst its lights, a distant and blurry face. Next year, I’ll return home. Will they still recognize me? I’ll bring something for everyone—a suitcase full of gifts. Yes, he wrote it—next year, he’ll come back. Next year, I’ll finally hold him in my arms again.

Dal Giorno del Ringraziamento al Natale il passo è veramente breve. Il tempo sembra proprio volare man mano che passano gli anni e dicembre sembra sempre più corto. Cento cose da fare, cento pensieri. Corrono via mattinate intere e sfuggono tra le mani pomeriggi che solo a novembre parevano lentissimi. Giorni frenetici tra le luci intermittenti, le decorazioni che arredano casa e gli allestimenti festosi nei negozi, tutto scappa veloce nella routine quotidiana, tra la lista dei regali da acquistare e le ultime consegne da sbrigare in ufficio prima della mezzanotte più luminosa. Sì, eccoci già arrivati alla fine dell’anno!

Mille pensieri, mille ricordi. Doveva essere ben più pesante lo spirito con cui aspettavano l’arrivo delle festività gli emigranti italiani che avevano oltrepassato l’oceano senza più voltarsi indietro, senza più tornare a casa, dopo quella prima interminabile traversata che aveva spalancato un mondo di aspettative e difficoltà impreviste. Chissà quanti avrebbero volentieri fatto un passo indietro, avrebbero evitato di partire o almeno sarebbero tornati ogni tanto là dove erano nati, dove li aspettavano gli anziani genitori, i parenti e gli amici dell’infanzia. Dove la casa, la piazza, la chiesa e una vita di fatiche erano tutt’uno con la memoria. Peraltro, anche quei primi anni in America non erano stati certo una passeggiata. Le terribili miniere, la ferrovia da costruire, il lavoro da elettricista, tutte le mattine con le mani ghiacciate a scaricare cassette di pesce, in fabbrica a stampare scatolette di latta, a ordinare file di mele e zucchine sul banco del mercato con un sorriso per tutti i clienti ma tanta fatica nelle ossa, le consegne da fare in fretta, il capo che urla in una lingua che non è mai davvero la propria, la saracinesca da tirare su circondati da volti estranei e sguardi torvi.

Natale senza i profumi del pane fragrante impastato sul tavolo della cucina, dei dolci semplici che si centellinavano nei giorni di festa ma carichi di quel sapore che riportava indietro nel tempo, agli sguardi allungati accanto al camino mentre sul fuoco cuocevano lenti i ceci e sul tavolo c’era il fiasco del vino che aveva richiesto tanta fatica ma che rincuorava ad ogni sorso. Senza quei muri rugosi che sembravano sempre vecchi e quei quattro mobili che bastavano per troppe persone. Tutto il paese che sembrava una sola famiglia. Natale con la messa al freddo in cui le candele riscaldavano i cuori, gli sguardi si incrociavano bassi e si pregava perché l’anno nuovo fosse generoso nei campi.

Domani riuscirò a mandare un po’ di risparmi a casa, ad aiutare mamma a comprare il corredo alla piccola Maria, le medicine per nonna Antonia e a rendere fiero papà che poteva vantare di avere un figlio là in America, dove tutti stavano bene e la vita non era mica come qui in questo paese povero, dove si poteva solo invecchiare di miseria senza realizzare sogni e campando di sudore. Se sapessero la fatica, lo sfruttamento, il nodo in gola, le monete che non piovono dal cielo e quanto è pesante sentirsi soli sotto questo cielo grigio che al paese non era mai così gelido perché la solitudine là non la si conosceva.

Eppure, anche in quel paese, fra quelle mura che sapevano di vecchio, poche cose e sempre quelle, Natale non era più lo stesso. Dentro quella casa più silenziosa, gli occhi sempre sulla sedia rimasta vuota, tutte le mattine alla finestra aspettando il postino che non arrivava mai e quella lettera conservata gelosamente nel cassetto del comò, che si rileggeva mille e mille volte e si riempiva ogni volta di nuovi pensieri e vecchi ricordi. Lasciava sempre il cuore appesantito, mentre le lacrime calde scendevano di nascosto sul viso. Nulla era stato più come prima da allora, da quando quel pezzo di cuore era partito con in tasca la giovinezza. Anche se le faccende erano l’unica distrazione ammessa, il pensiero tornava sempre a quel figlio lontano e in fondo alla pentola un mestolo di minestra era suo. Chissà come stava, se viveva in una casa spaziosa e pulita e le luci della grande città illuminavano a giorno le strade lunghissime e affollate come le stelle del cielo riempivano le calde notte estive.

Un raccolto dopo l’altro, un inverno dopo l’altro. Matrimoni, nascite, acciacchi e altre primavere. Tanti anni passati, qualcuno era ritornato portando notizie lontane. Il paese sempre più vecchio e vuoto di qua, i grattacieli sempre più fitti d’auto di là. Quante cose erano cambiate, quanti amici passati, quante vite trascorse. Ogni Natale carico di preghiere e speranze, ogni Natale che nascondeva tra le luci un volto lontano e sfocato. L’anno prossimo tornerò a casa, chissà se mi riconosceranno, porterò qualcosa a tutti, una valigia piena di regali. Sì, l’ha scritto, fra un anno tornerà, fra un anno finalmente lo riabbraccerò.