Tucked away in the province of Enna, between the Nebrodi and Madonie mountains in the heart of inland Sicily, lies a village that borders Gangi (in the province of Palermo) and Nicosia (in the province of Enna). Its name is Sperlinga, home to fewer than 700 residents. The name – Sperrënga in Gallo-Sicilian and Spilliňga in Sicilian – derives from the Greek spelonca, meaning “cave.” And fittingly so: the village, recognised among Italy’s Most Beautiful Villages and often described as a “royal rock-hewn dwelling,” is carved into an enormous sedimentary outcrop. The surrounding area is dotted with numerous caves dug directly into the soft sandstone.

Archaeological evidence shows that this territory and its cave dwellings were inhabited as far back as four thousand years ago. The first historical reference, however, appears in 1082 in a charter issued by Count Roger. Soon after, the area was colonised by Lombard settlers, either from northern Italy or from Lombard communities already established in Sicily. The legacy of that colonisation endures in the local dialect, a variant of Gallo-Italic known as Sicilian Gallo-Italic, still spoken today not only in Sperlinga but in several other Sicilian towns that trace their origins to migrants from the provinces of Novara, Asti, and Alessandria.

A 1239 document refers to Sperlinga as a castrum – a fortified settlement with castle structures. The village’s identity has long been shaped by the noble families who owned the castle and its surrounding fiefdom: Ventimiglia, Natoli, Rosso, and Oneto. Among them, Prince Natoli notably expanded the village and commissioned the Church of Saint John the Baptist outside the castle walls. The first parish records date back to 1612. In 1658, his son Francesco Natoli Maniaci transferred ownership of the castle and fief to the Oneto family, granting them the title of Dukes of Sperlinga – though the Natolis retained the title of Princes of Sperlinga.

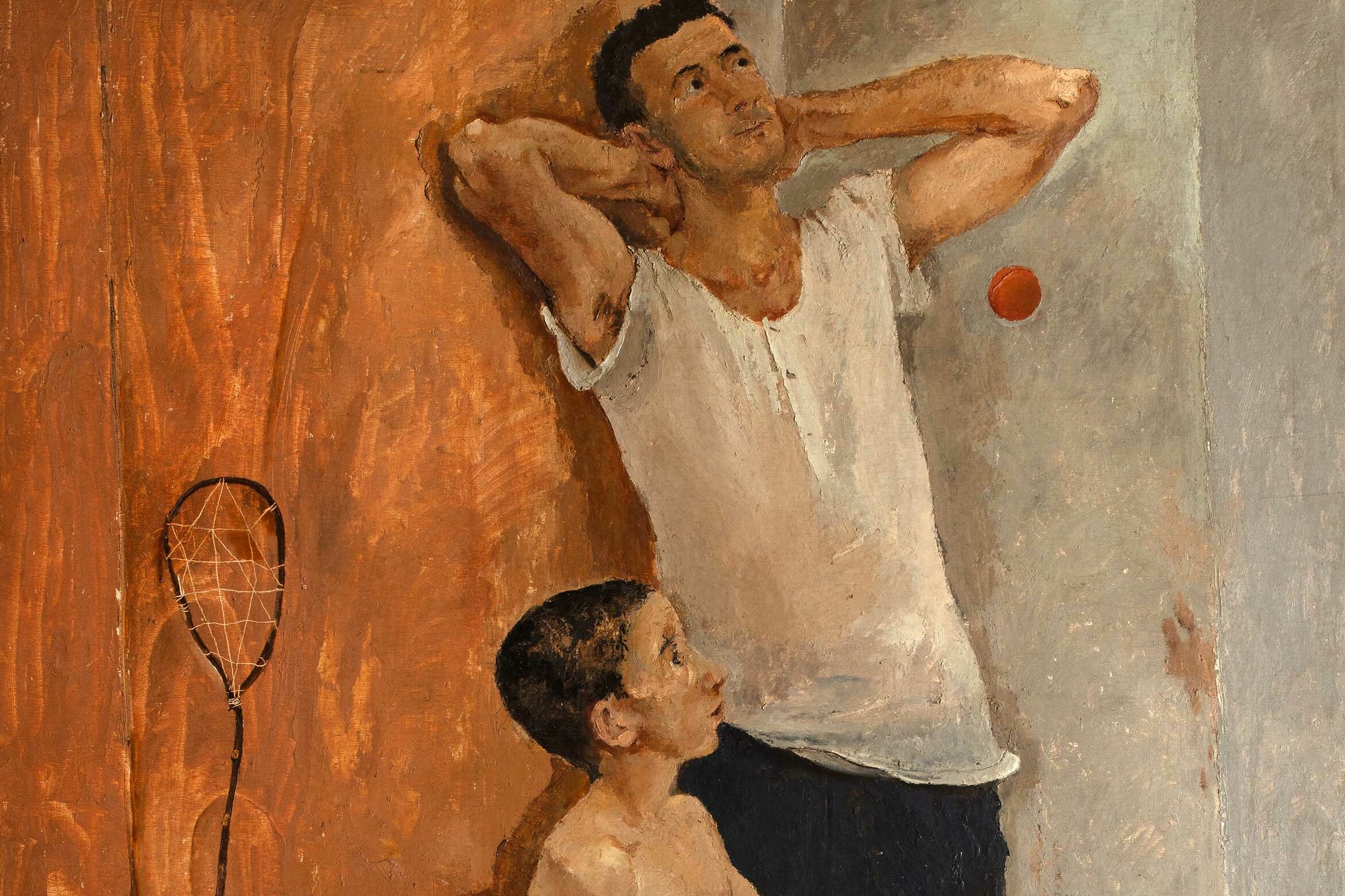

Over the centuries, Sperlinga caught the eye of several prominent visitors. In 1776, French painter Jean-Pierre Houël included a view of the town in his Voyage pittoresque. Two years later, fellow artist Jean Claude Richard de Saint-Non also visited and painted a scene of the village. Artistic attention continued into the 20th century. In July 1943, celebrated photojournalist Robert Capa—born Endre Ernö Friedmann and later a naturalised American—took a photograph in Sperlinga that became an emblem of the Allied landings in Sicily. The image was published in Life magazine and went on to become a symbol of wartime reportage. In 1955, the renowned anthropologist, writer, and photographer Fosco Maraini – father of author Dacia Maraini – photographed the town for the Alinari archive, the world’s oldest photographic collection.

Each year on August 16, the district of “Balzo” – with its carved, overlapping alleyways that form a veritable rock-hewn village – comes alive with the Sagra del Tortone. During this celebration, visitors are invited to taste a variety of local delicacies, all rooted in Sperlinga’s culinary traditions. The star of the event is the tortone, a typical and much-loved sweet: deep-fried, dusted with sugar and cinnamon, and perfect for nibbling while strolling past artisan workshops lining the village streets. As visitors explore, a historical parade winds through the town, culminating in the crowning of the Dama dei Castelli di Sicilia, the Lady of the Castles of Sicily.

In the days leading up to Ferragosto, the town’s neighbourhoods, each represented by their own Lady, compete in a series of traditional games. The Lady who scores the highest is named Castellana of Sperlinga. On August 16, she parades through the village alongside the other winning Castellane from Sicily’s Gallo-Italic towns, all dressed in historical costume. Every participant in the procession wears traditional attire, and the Dama dei Paesi Gallo-Italici – Lady of the Gallo-Italic towns – is chosen by a special jury. The festivities continue well into the evening in Castle Square with music, dancing, theatrical reenactments of historical events, and, of course, a grand fireworks display.

Beyond these traditions, parades, and the celebration of its patron saint, Saint John the Baptist, on June 24, Sperlinga is home to one of Italy’s most unusual fortresses: a rare example of a castle partly carved into the rock and partly built using the very stone excavated on site. The oldest parts of the structure date back to between the 12th and 8th centuries BC, before the arrival of the pre-Greek Siculi peoples, and specifically to around the year 1080. Over the centuries, ownership of the castle passed between several noble families: the Ventimiglia counts, the Natoli princes of Sperlinga, the Oneto dukes, and finally Baron Nunzio Nicosia. In 1973, the heirs of Baron Nicosia donated the castle to the municipality of Sperlinga.

At the entrance of the fortress, carved into the pointed arch, stands a Latin inscription: “Quod Siculis placuit, sola Sperlinga negavit” – “What pleased the Sicilians, only Sperlinga denied.” The phrase refers to the Sicilian Vespers uprising of 1282, when the entire island revolted against Angevin rule. According to tradition, Sperlinga alone remained loyal to the French crown, with a garrison of Angevin soldiers holding out in the castle for over a year. The inscription itself was added later, in the late 16th century, as a retrospective symbol of the town’s singular stance in Sicilian history.

Since prehistoric times, the rocky cliffs that now tower above the village served as shelter—crude refuges carved directly into the stone. Today, those ancient hideaways have been transformed into homes, complete with doors, windows, and even the occasional balcony. The few that escaped modern urban development—untouched by roads and concrete—stand as the last silent witnesses of the ancient peoples who once lived there. Wandering through the castle’s rooms, hollowed out of sandstone, one breathes an atmosphere steeped in antiquity—a sense of prehistory, of a people who settled there a thousand years before Christ, and who enjoyed a landscape likely far more unspoiled and breathtaking than today’s.

There must once have been a drawbridge, leading into the heart of the stronghold. Traces of human ingenuity are still visible: the rock-hewn spaces were transformed into stables, complete with farriers’ workshops and metalworking stations, storage rooms for food supplies, water cisterns, and even a prison. In one circular chamber, twelve small niches are carved into the walls—possibly a place of worship, or, according to another theory, part of an ancient timekeeping system. A steep staircase carved into the rock leads up to the tower, from which the view stretches out in a dramatic, sweeping panorama.

But the caves don’t end there. The entire cliffside of the castle facing the village is riddled with openings that, though they resemble natural formations, are in fact ancient artificial caves—excavated by human hands in times so distant they’ve slipped into legend.

To visit Sperlinga and its castle is to step out of time. The entire site is a testament to the enduring relationship between humankind and nature—a place where even in the most remote of eras, people used their ingenuity not to conquer the environment, but to adapt it thoughtfully to their needs, always in harmony with the land that sustained them.