A century ago in Black Diamond, Wash., the freight trains arrived empty twice a day and twice a day they left, loaded with coal. Railroad assistant Amos Ungherini would go down the line each day in a hand-pumped “speeder” to weigh the cars. Back then, the railroad was more than just a way to get coal to market. It was the lifeblood of the town.

Ungherini and others of Italian descent worked hard in and around the coal mines of Washington. And unfortunately, some paid the ultimate price.

On April 26, 1907, a methane gas explosion in a coal mine outside Black Diamond took the lives of seven men. Among the dead, as reported by the Seattle Daily Times, were three Italian miners: 23-year-old Joe Belmonti and 25-year-old Albert Domini, both unmarried, and Philip Domenico, married with one child.

Although Washington was never a huge coal-producing state, coal was critical to the westward expansion, feeding the locomotives that transported everything from livestock to machinery to people. During the early 1900s, there were about 5,000 men working in the state’s coal mines.

Coal was king in Black Diamond, a small town about 25 miles southeast of Seattle along the Cascade Mountain range. A company town, it was built for, and named after, the Black Diamond Coal Company of Nortonville, Calif. When the company opened the Black Diamond mine, some miners moved up the coast from California while others came from farther afield, including Italian immigrants from Sicily, Calabria and Basilicata who were eager to escape the bone-wrenching poverty of their native land.

In those days, everything that came into town moved by rail. For a time, Ungherini lived in the Black Diamond railroad depot. “The life of the town centered in the depot,” Ungherini recalled in a 1980s newspaper article. “Through the express, freight, Western Union, one way or another, I think I knew everybody in town.”

Many of the early miners in Black Diamond were first-generation Americans of Welsh or Italian descent. The Welshmen, profiting from a long tradition of coal mining in their native country, often had some mining experience. This meant they merited the more skilled positions and were usually paid higher wages. The Italian immigrants, many illiterate and unskilled, supplied the muscle. Laborers were paid about $2 for a 10-hour shift.

The company owned everything. Families could buy their own houses, but the company owned the land and leased it to a family for $1 a month. Only one church was deemed necessary for such a small town so Sunday services were held on a rotating basis to accommodate the different faiths. Ethnic groups tended to cluster together in neighborhoods where they could speak their own language and enjoy their own foods. The Italians settled just below the train station.

Working conditions in the mines were extremely dangerous and explosions were common. Accident insurance was nonexistent. Those who could escape the coal mines did so. Angelo Merlino, whose company Merlino and Sons is well known today in Seattle, started importing cheese, pasta and olive oil in bulk while he was still working in the mines. In 1900 he quit mining altogether and opened a store that became so successful he began importing Italian food by the shipload.

In 1904, the Pacific Coast Company, a New York-based enterprise, bought the Black Diamond mine and with it, the small town. The 1907 accident happened under their watch. The official inquiry determined that the seven deaths were caused by “an explosion of a pocket of gas, which was brought down by an unavoidable cave and ignited by some unknown miner.” Pacific Coast was ruled not at fault.

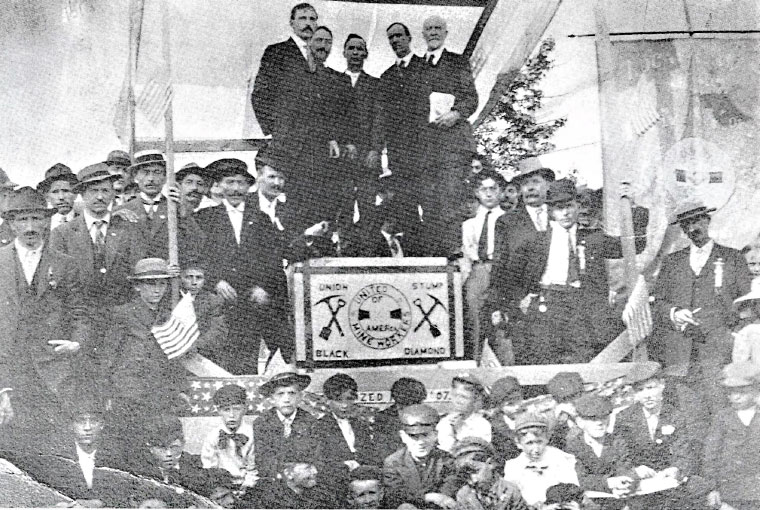

About three weeks after the accident, on May 15, 1907, the coal miners organized Local 6281 of the United Mine Workers of America. But when union members tried to hold meetings near the train depot, the mining company would not allow them to congregate or meet on company property. Several hundred workers walked outside the town limits, just beyond the cemetery. One of the men jumped on a fir stump to address the group. That stump served as their meeting post for many years and exists today, albeit in a block of concrete, marked by a commemorative plaque.

Washington’s last underground coal mine, Rogers No. 3 Mine at Ravensdale, near Black Diamond, closed in 1974, and the portal was dynamited shut a year later.

The town of Black Diamond has not grown much since the early 1900s. In 2013, the population was about 4,200. Most of the Italian families stayed in town; about 8 percent of current residents claim Italian heritage.

The town’s coal mining history still figures prominently. Two “Welcome to Black Diamond” signs in the shape of coal-mining carts greet drivers heading into town. And the original train depot where Amos Ungherini once worked now houses the Black Diamond Historical Museum.

Outside the museum, visitors can peer into a recreated coal shaft complete with partial tracks and lanterns. On the main floor, mining tools, medical equipment, furniture and other items from Black Diamond’s past are displayed. It’s also possible to visit the nearby union stump and the cemetery, where a stroll around the grounds will turn up many Italian names.

The volunteer-run museum is open three days a week. For directions and hours, visit: http://blackdiamondmuseum.org.

![Coal was king in Black Diamond, a small town about 25 miles southeast of Seattle along the Cascade Mountain range. Russell Lee [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Coal was king in Black Diamond, a small town about 25 miles southeast of Seattle along the Cascade Mountain range. Russell Lee [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://italoamericano.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/miner1.jpg)