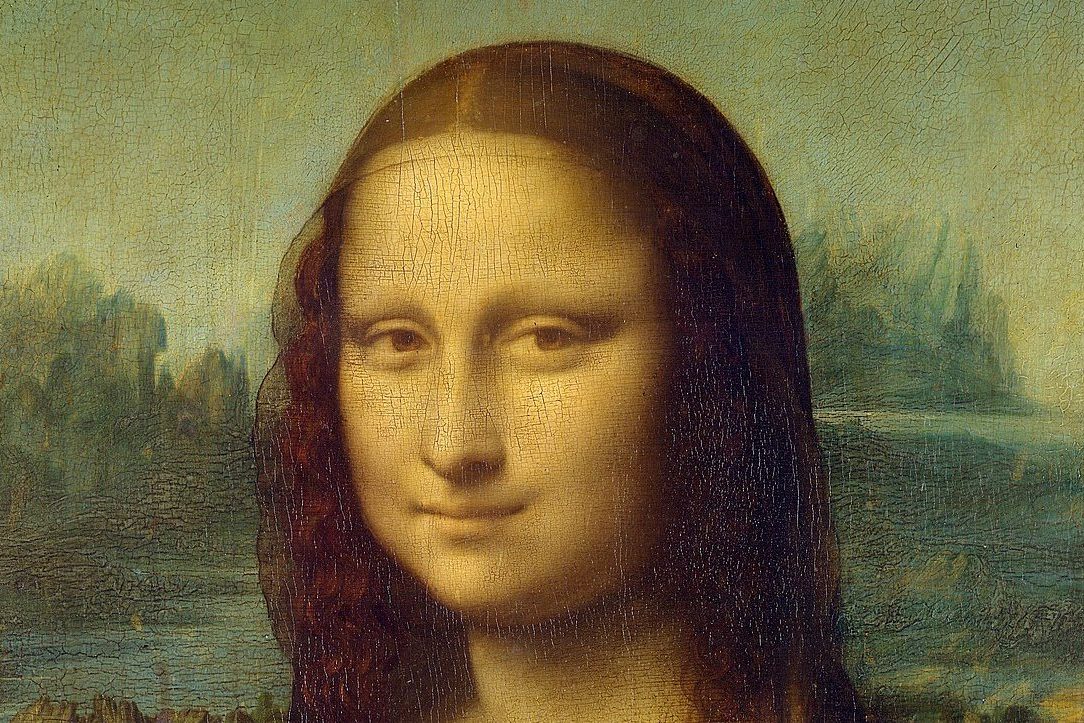

Like so many women before her—let’s say, the Mona Lisa—La Schiava Turca (ca. 1531–1534), or The Turkish Slave, is most famous for an enigmatic quality that begs us to guess at her origin and the source of a coquettish, knowing smirk. In fact, given the Turkish Slave’s undeniable confidence and what some scholars have called an “aggressive” posture, it seems almost unbelievable that she was ever mistaken for a Turkish slave at all.

In a rare fieldtrip from her beloved home at the Galleria Nazionale di Parma, La Schiava Turca is continuing her American debut at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco after a stop at the Frick in New York. Her arrival was marked by a lecture and opera performance on July 26, and a follow-up lecture will take place on September 13, 2014, featuring Mary Vaccaro, PhD, Art History professor and area coordinator, University of Texas, Arlington, to give museum-goers a second chance at peeking into the possible identity of the woman in the painting.

Francesco Mazzola (1502 – 1540) was better known as Parmigianino, a famous son of his namesake city, Parma. Sometimes called “Raphael reborn,” Parmigianino was perhaps as famous for his short and erratic life as for his immense talent. The artist has been described as so immersed in his own work that he was unable to complete much of it, and he died young and penniless, with debtors after him for running out on a commissioned project.

In an infamous show of ego, but also a testament to his brilliance, Parmigianino is reported to have made his debut in Rome at the age of 21 with a gift of his own portrait to the Pope, now known as Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror (ca. 1524). A review of a 2001 show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Correggio and Parmigianino: Master Draughtsmen of the Renaissance,” surmises that Parmigianino’s bold and elegant use of color was a reflection of his many moods (and a contrast to his mentor Correggio’s much softer palette).

Though Parmigianino was a skilled etcher and engraver, his paintings have proven more enduring for their signature use of elongated forms and a twining, elegant stroke, such as in the controversial Madonna with the Long Neck (ca. 1535–1540)—Parmigianino worked on the Madonna for six years before leaving it unfinished upon his death.

Among the signifiers that the woman in La Schiava Turca was no Turkish slave are her balzo, a popular style of headdress among Northern Italian women at court, and poetic symbols like a Pegasus on the headdress and the playful ostrich plume that fans against her breast. As explored by Karen Rosenberg in a New York Times review of the Frick exhibition earlier this spring, the words for feathers (piume, penne) and pen (piuma, penna) in Italian are very similar, and it would not be a far stretch of the imagination to think of Parmigianino using this play on the literal and metaphorical to represent his subject’s literary prowess and/or connections.

Indeed, many have speculated that La Schiava Turca is actually the poet Veronica Gambara, who could have been known to the artist through mutual friends. Likewise, theories about other potential noblewomen in Parmigianino’s circle are common. Why he would have chosen to paint the woman, however, and if there is any meaning behind the portrait beyond simple ideal poetic beauty, replete with Renaissance hallmarks of love like the chain bracelet on her right wrist, remains solely at the viewer’s leisure to contemplate.

The Poetry of Parmigianino’s “Schiava Turca,” exhibit at the Legion of Honor will be rounded out with Mannerist and Renaissance paintings from the museum’s own permanent collection, including Madonna and Child with Two Angels (ca. 1525) by Pontormo and Agnolo Bronzino’s Portrait of an Elderly Lady (ca. 1540), in addition to other artists. The exhibition will run through October 5, 2014. For more information visit, http://legionofhonor. famsf.org/legion/exhibitions/poetry-parmigianinos-schiava-turca