Rosolio has enjoyed popularity in Piedmont and Sicily for centuries, drunk by hosts and their guests on special occasions to signify and convey good luck. It’s a floral liqueur that has often been used as the base for other alcoholic beverages in the past but this year it’s enjoying a surge in popularity in its own right and barkeeps across Europe are going mad for its unique flowery flavor. Here’s what you need to know and how to drink it.

The origins of rosolio, or Ros Solis meaning the “dew of the sun” in Latin, as it was originally called, are hazy but many suggest it was first distilled in Renaissance Turin from the Italian Sundew plant, Drosera rotundifolia

What is Rosolio?

The first known mention of rosolio in literature was in 1796 according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, but it probably dates back even further as distilled cordials, or liqueurs, had been used as medicinal tonics as far back as the 1400s.

Used originally as alcoholic medicines, the cordials of the late 15th century were prescribed in small doses to revive heavy souls, revitalize the heart and even as aphrodisiacs, reinvigorating parts of the body other medicines couldn’t. But imbibers soon discovered an added benefit to these medicines, increasingly drinking liqueurs for their intoxicating properties rather than their purely therapeutic benefits. And by the 1700s they were more and more drunk for pleasure, not just the relief of pain.

The origins of rosolio, or Ros Solis meaning the “dew of the sun” in Latin, as it was originally called, are hazy but many suggest it was first distilled in Renaissance Turin from the Italian Sundew plant, Drosera rotundifolia. The alcoholic infusion was made from fresh petals of the insectivorous bog plant together with sugar, water, vanilla pods and a raw spirit. Its thought the original recipe also included spices such as cubeb (tailed pepper), galingale and grains of paradise (both from the ginger family), all of which brought a stimulating punch of aphrodisiacal heat. No wonder then that self-acclaimed English doctor and writer of medical tomes William Salmon describes Rosolio as a golden yellow sundew drink that “stirs up lust” in those who drink it.

Small producers typically distilled Rosolio liqueurs locally in convents, monasteries and homes so methods and flavors relied heavily on the flowers growing in the cloisters, gardens and meadows nearby

And the liqueur wasn’t just enjoyed in Italian company at this time. It had already crossed the English Channel to Britain, where Rosolio was served at the top banqueting tables to wash down other licentious foods including kissing comfits, or perfumed sugar sweets made from sugar, musk, civet, ambergris and white orris. William Shakespeare also makes mention of them in his play “The Merry Wives of Windsor” when Falstaff exclaims “Let the sky hail kissing comfits.”

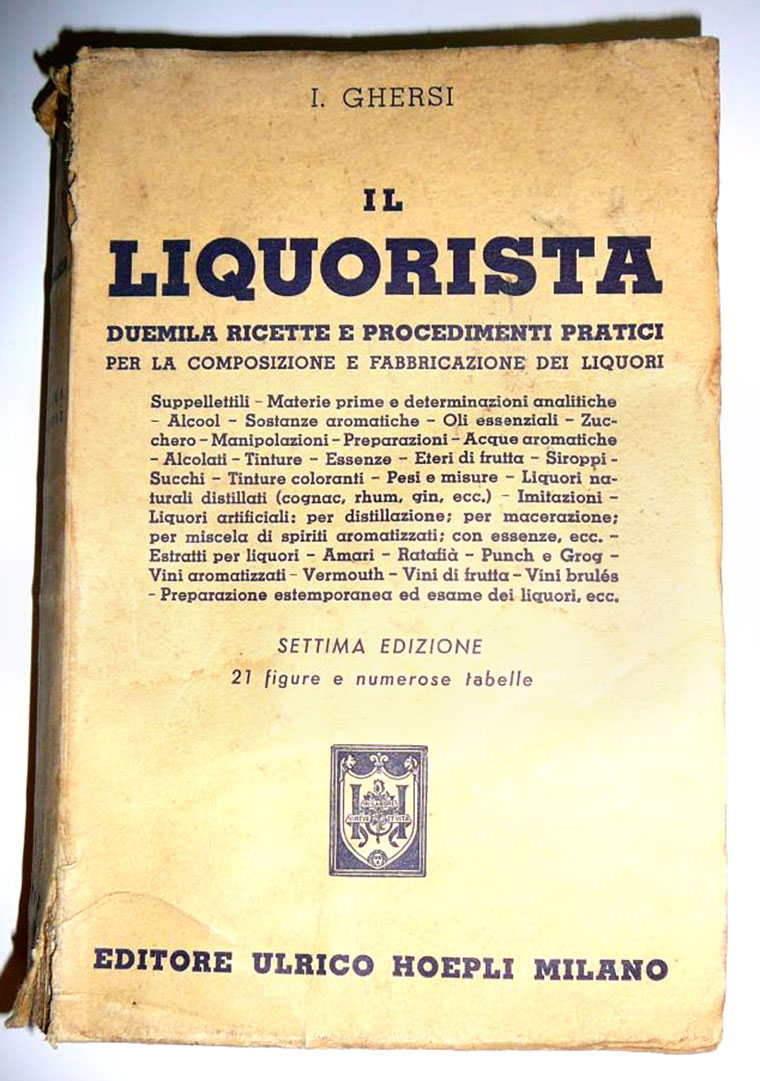

In his 1921 Manuali Hoepli Liquorista, instructions for liqueur-makers, Italo Ghersi, a respected mathematician and accomplished chess player, catalogued over 2000 different Italian liqueurs

As the distillation and consumption of Rosolio as a recreational drink increased, so too did the variations on the recipe. Small producers typically distilled Rosolio liqueurs locally in convents, monasteries and homes so methods and flavors relied heavily on the flowers growing in the cloisters, gardens and meadows nearby. And where Sundew wasn’t available home distillers started to substitute other botanicals, especially those in close regional abundance. From rose to lavender, orange blossom to cinnamon or lemon to fennel this delightful liqueur, over the years, came to mean many different flavors to many different Italians from north to south. And with an alcoholic content of anything from 20 to 30% the finished drink had a good kick.

Over the decades the taste for liqueurs grew and rosolio drinking diversified along with its flavor. It became popular in both village celebrations and royal courts toasting baptisms, weddings and royal occasions.

In his 1921 Manuali Hoepli Liquorista, instructions for liqueur-makers, Italo Ghersi, a respected mathematician and accomplished chess player, catalogued over 2000 different Italian liqueurs (not to be confused with “liquor,” the American term for spirits). Of those, Ghersi listed 55 different variations on the rosolio recipe alone, more than for any other single category in the book. But although there were dozens of variations, rosolio’s popularity was on the wane, confined to the back of the royal drinks cabinet, thanks to a large scale switch in the mid 1800s by the royal court and commoners alike to vermouth, another Turin concoction.

But the story of the people’s drink doesn’t end there.

The recent success of Aperol Spritz, bursting borders to take over the European bar scene of late, has paved the way for other Italian aperitivi like rosolio to make a come back, both in its home country and wider afield. Contemporary distillers are reviving and revitalizing grandma’s old recipes taking the domestic drink to the contemporary city-center cocktail menu. So as rosolio’s sweet, floral, citrus overtones are introduced to a new audience, how should we drink it?

How to serve rosolio

Discerning barkeeps are forever looking for new twists on old drinks, especially those with a story, but with rosolio they have a complete compendium of florals with which to work. And unlike Aperol, which has a recognizable bitter orange tang, the newly launched rosoli have their own individual bouquets.

For the medicinally green-bottled Rosolio di Bergamotto, for example, the initial citrus sharpness gives way to a sweeter lavender note and finally a bitter bergamot finish making it the perfect accompaniment for prosecco. Distiller and world-class bartender Giuseppe Gallo recommends a 50:50 mix of his rosolio, based on his grandma’s old recipe, with a good prosecco garnished with 3 plump green olives to add saltiness to cut through the floral overtures.

Meanwhile in London Thierry Brocher of Sanderson’s bars uses his 15 years experience in the business to combine rosolio with gin and vodka to add an Italian spin to some cocktail classics. Why not try his rosolio infused spritz, gin and tonic and vodka tonic using the liqueur to give a citrus botanical lift. Rosolio is also said to work well in a martini offering another mouth-watering temptation to refresh the long summer evenings, or why not enjoy it in a tiny, colored period shot glass as they would have done back in its heyday. The options are endless.

So next time you’re stumped for inspiration at the bar why not ask your barkeep for rosolio. Its Renaissance alchemy turns the delicate flowers of Italy’s gardens and meadows into a golden, perfumed liqueur fit for a king. And whether you drink it straight to enjoy its complex layers of botanic charm or mix it with spirits to tease out its aromas, it is bound to make conversation go with a flow. Cin cin!