Joe Medeiros and his wife/producer, Justine Mestichelli, after a pernickety investigation, lasted about five years, were able to connect all the dots and to paint an exhaustive picture about the Mona Lisa’s theft, on August 21, 1911.

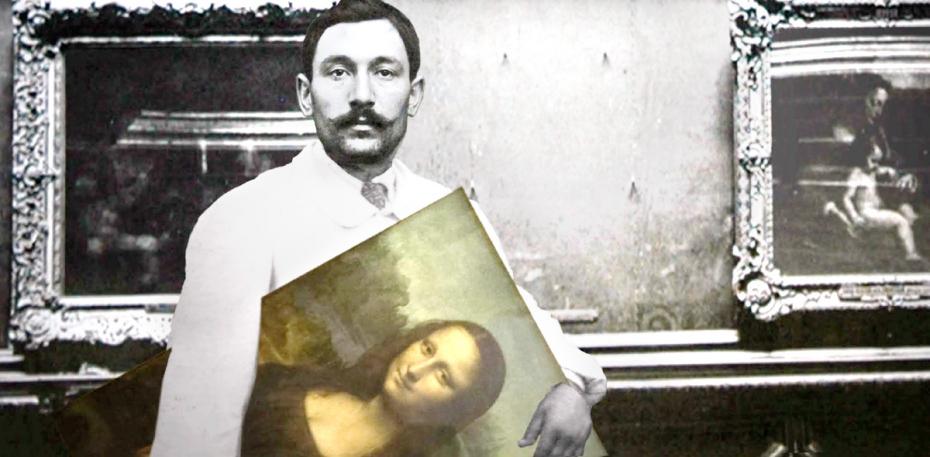

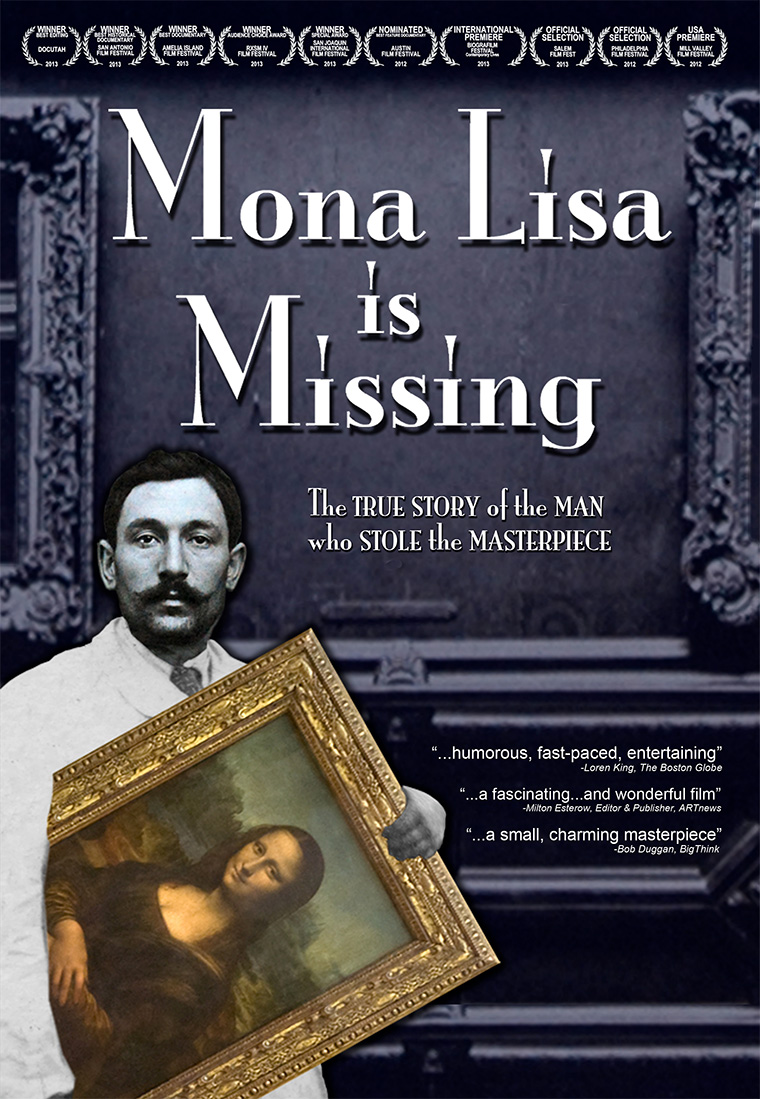

The multi-awarded documentary, Mona Lisa is Missing, casts light on the motivations, which urged Vincenzo Peruggia – a house painter who emigrated to Paris from the small village of Dumenza (in the Italian region of Lombardy) – to steal from the Louvre one of the most recognizable icons worldwide.

Dear readers, do not worry! The film is not going to spoil the enigma, around the Mona Lisa’s smile.

The entertaining documentary is viewable on Netflix. Besides, DVDs, filled with extras, are available upon request on the official website: www.monalisamissing.com.

Better yet, if you want to hear directly from the filmmakers, Joe and Justine are currently taking part to Q&A, following public screenings across the United States, and they will fly to Europe, soon.

Joe and Justine, what are your cultural backgrounds?

I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I’m Italian on my mother’s side and was raised close to that culture. My father was Portuguese, but he was born in Hawaii. Thus, we were uprooted from Portuguese culture.

One of my uncles was an artist, so I developed a certain familiarity in the field. One of my favorite artists of all times was Leonardo Da Vinci.

In 1976, when I stumbled on a book’s passage, reporting that Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was stolen in 1911, I got caught up in the whole matter.

As far as education, I majored in Filmmaking and, then, started to work as an advertising writer.

I discovered to have a knack for joke writing and became head writer for The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. I collaborated with Jay for twenty-years and, by working on the talk-show, I had the chance to hone my editing skills, too.

Writing jokes helped me to vent my frustration, for not being able to reenact in a screenplay, what drove Vincenzo Peruggia, an humble Italian immigrant, to steal one of the artistic masterpieces of all times.

In 2008, I found out that Vincenzo’s eighty-four years daughter, Celestina, was still alive. That’s what urged me to realize a documentary about the theft, instead of a fictional film.

We were not entirely new to the documentary form, given that we had realized short documentaries for charitable causes.

It took us about five years to put together all the missing pieces and complete the feature length documentary film.

As you mentioned, your initial goal was to write for the screen a fictional version of the Mona Lisa’s heist. What got in the way?

I didn’t know enough about Vincenzo Peruggia’s family and profession. I had access to very limited sources, in the US.

There was also the language barrier, given that both of us could speak neither Italian nor French.

It is one thing to embellish the details of one’s life and quite another to make up the bulk of it. I didn’t yield to the latter scenario and, instead, wanted to tell the truth about the man’s motivations.

At last, the availability of documents and the reachability of people, through the internet, made the idea of a documentary feasible.

The episode of Peruggia, an highly skilled Italian immigrant in Paris, mistreated by his French coworkers because of jealousy and rivalry, tells us about the inequality faced by immigrants worldwide. Its lesson is still fully worthwhile today, as it was back then.

Did you have an hard time in funding the film?

To fund a documentary is always hard. Luckily, the position I had in TV, paid me well, and we were able to draw from those personal finances.

We managed to work economically, because we owned our own equipment, hired a small crew, and we had the in-house skills to rough cut the film.

I had to learn the basics of animation, to save as much money as possible. We collected postcards, clippings of newspapers, photographs and we assembled those together in a creative way. I spent two years, working at the graphics.

Lots of researchers from France and Italy, volunteered to help us, because they really wanted to take part to the project.

The large share of investment went into post-production, including sound mixing and color correction. In fact, we hired a professional editor for the final editing, and a composer recorded the soundtrack.

I find very interesting how you physically incorporated the huge amount of sources and documents, utilized for your research, into the narrative itself. Could you expand on that?

I’ve been studying the topic for forty years. I was extremely excited, when I finally had the chance to look at the original letters, written by Peruggia, during his imprisonment in Florence, and I decided to put them on screen.

One of the photographs, a long shot of Vincenzo wearing a hat, was unpublished, so we were the first to see it.

Given that there is no period footage from the early nineteen hundred, we had to fill up the screen with other visual elements.

Besides, the documents helped to legitimate our investigation, which is extensively based on primary sources.

We gathered so much material, that the process of selection turned out to be the most difficult one.

Our initial cut amounted to four hours of footage. In the DVD, we have included ninety minutes of extra content, which didn’t found place in the film.

Usually, filmmakers avoid showing the written word on screen, as much as they can, since it’s not cinematic enough. Your use of newspapers’ headlines, instead, is very effective. How did you achieve that?

I believe that it’s more effective to show the historical information, as it was reported back then, instead of simply stating the facts.

The newspapers’ headlines make everything more real and objective. If I tell the audience that “the French Police Commissioner of that time was regarded as the greatest policeman in the world”, it may sound like my opinion, as opposed to the information given by the newspaper of that day.

We’ve never been stopping our efforts in collecting original material from the early nineteen hundred. Recently, I bought on eBay a period copy of a newspaper, featuring the picture of the French guard, who discovered the empty frame, left behind by Peruggia in the Louvre’s service staircase.

What are you working on, right now?

For about a year, we have been shooting a documentary about the procession tradition of St. Peter’s Italian Catholic Church in Downtown, Los Angeles.

Our project, funded by the Robert Barbera’s foundation, documents how the tradition of processions, in celebration of Saints, came to the US, when Italian immigrants settled here.

The ultimate goal is to encourage the preservation of this tradition by the second and third generations of Italian immigrants.

Surges of Italians, hailing from villages – each devoted to a different patron saint – brought that tradition with them, when they came here.

There are twelve distinct processions, with a frequency of one or two per month. Those are preceded by a Mass (in Italian) and followed by a rich banquet, at the Casa Italiana, annexed to the above mentioned church.

Tell us more about your contacts with the Italian-American community in Los Angeles?

As far as Justine, both of her parents are Italian-American. During the realization of the documentary, she obtained the Italian citizenship.

Our children are Italian citizens as well, and I am in the process of becoming such.

We are both members of the Patrons of Italian Culture, and we have been screening our documentary in several Italian-American associations and Italian Departments in universities, across the US.