On June 11th 2002 the United States House of Representatives righted a wrong that had persisted for over 130 years. They passed a resolution honoring Antonio Meucci, an Italian migrant who lived in Staten Island, for his key contribution to the invention of the telephone. But to this day, his name is still overshadowed by Alexander Graham Bell’s.

So who was Meucci and did he really invent the first telephone?

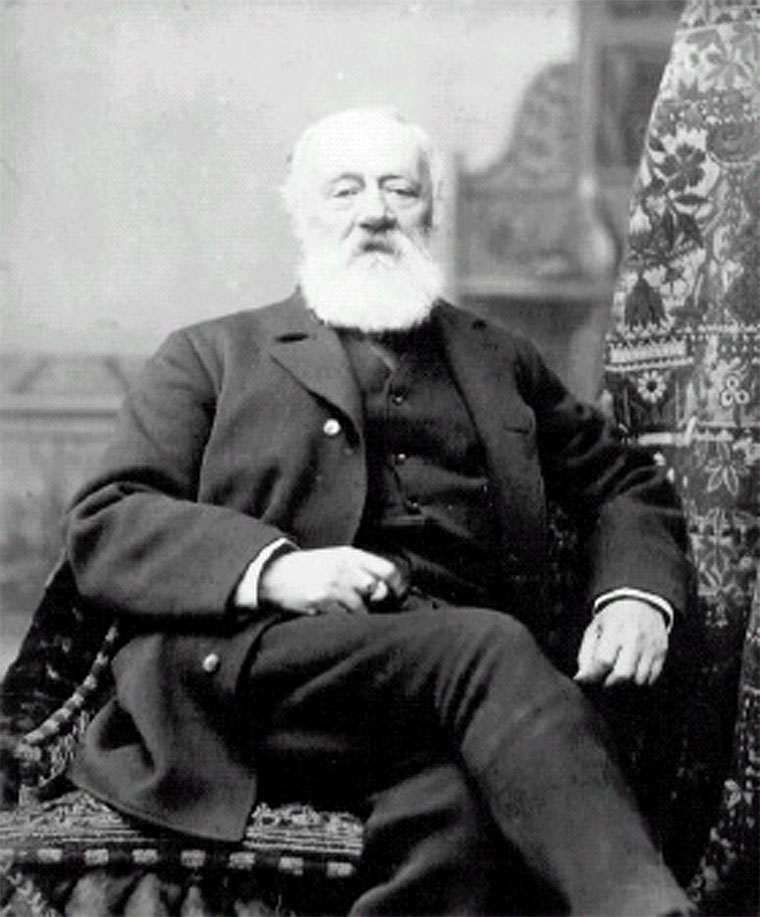

Antonio Santi Giuseppe Meucci

Born on 13th April 1808 near Florence, Antonio Santi Giuseppe Meucci was the eldest of nine children. He was a talented student with an inquisitive mind entering Florence’s Academy of Fine Arts to study physics, chemistry and mechanical engineering aged just 15. After just two years Meucci was forced to take a part time job working for the Florentine government to fund his studies. This wouldn’t be the last time that Meucci’s life took a turn due to lack of funds.

His keen insight was perfectly suited to science and by eighteen he had already invented a new chemical propellant for fireworks. A job in theatrical special effects beckoned at Florence’s Quarconia Theater. And from there he quickly moved on to the Teatro della Pergola opera house, one of the most technologically advanced theatres in Italy at the time. It’s here that Antonio took his first steps to create the telephone.

Sound inventions

Meucci loved to play around with the electromagnetic machines used to generate lightning effects, he even had a small lab in his rooms up in the theatre’s loft. And ever a problem-solver, the young scientist decided to tackle a bugbear of the stagehands; how to communicate across the large stage to co-ordinate scenery changes safely. Meucci quickly developed a sound amplifier like a megaphone, halving the time taken to change scenes and laying the groundwork for more inventions.

Off to Cuba

Italian opera was widely held as the best in the world, so when the chance came to move to Cuba with the Pergola opera company, Meucci and his new costume tailor wife, Ester, jumped. The company settled in the Teatro Tacón in 1835, now the Gran Teatro de La Habana Alicia Alonso and home to the Cuban National Ballet. Antonio worked as the mechanical supervisor and Havana would see the next big breakthrough in Meucci’s telephonic work.

Antonio continued his experimentation in Havana, gaining a reputation as one of the few scientists developing new electrical technologies. And in 1848 he was approached by a small group of doctors keen to explore electricity’s medical applications. This would prove pivotal.

Meucci’s electrical shock therapy required patients to put a metallic tongue in their mouths. And it was during one of his experiments that he realised that electricity could be used to transmit sound along a wire as when a patient cried out Meucci heard it in another room via the apparatus’s copper wiring. That moment was the inspiration for his talking telegraph, telegrafo parlante, teletrofono or the telephone that would change the world.

Pronto!

Meucci knew he had something unique and immediately started work on voice transmission. And within 2 years he’d decided to emigrate again, this time to New York, to capitalize on his work just as American Samuel Morse had recently done with his morse code telegraphic system.

The couple settled in Clifton on Staten Island in 1850. And the experiments continued in the basement lab. But tragedy struck 4 years after their arrival when Ester fell victim to rheumatoid arthritis and was confined to bed. Despite the blow, Meucci was spurred on and in 1857 he set up the first working voice transmission equipment between his basement workshop and his wife’s bedroom so he could communicate with his beloved Ester.

Meucci spent the next 12 years building several prototypes but crucially lacked the personal funds to patent, protect or commercialize his idea; patents cost money. So instead he publicized his invention through Italo-American newspaper L’Eco d’Italia in an attempt to drum up financers but sadly it did little to protect his product and may even have given his trade secrets to his rivals.

Antonio wouldn’t lodge a patent caveat to announce his invention until December 1871. And once again lack of funds was an issue; the caveat lapsed after just 2 years leaving the door open for the Scottish gentleman inventor Alexander Graham Bell to lodge a patent for his “phonautograph” in 1875.

And crucially the Scot had the one thing that Meucci lacked; funds. Within a year Bell had set up the Bell Telephone Company going on to become a millionaire as voice transmission took off. Meucci on the other hand died in March 1889 without ever capitalizing on his invention or receiving any recognition for his contribution to technology, despite attempts to reclaim credit through court action against Bell.

It would take more than a century for that wrong to be righted. And although some still argue that Bell’s inventions were fundamentally different to Meucci’s, the Italian was undoubtedly developing voice transmission systems long before Bell was even born. Whether Meucci would have succeeded with financial backing we’ll never know, but clearly he was well ahead of his contemporaries for years and just pipped at the final post. So next time your phone rings remember we owe at least some of the original technology to a Florentino called Antonio Meucci. Grazie Antonio!