Admittedly, the times of Machiavelli were very different from today’s, and his own take on how to lead successfully a country would be now considered extreme by some and plainly unacceptable by most. However, this polyhedral figure of Italian history and culture remains central for the development of political thought, a certain representative of Italy’s contribution to the evolution of western culture.

Who was Niccolò Machiavelli?

Everyone who went to school in Italy knows that “it’s Niccolò with two ‘c’s’ and Machiavelli with one!,” a common sentence literature teachers in middle and high school would repeat ad nauseam to get us students to remember Machiavelli’s name’s proper spelling.

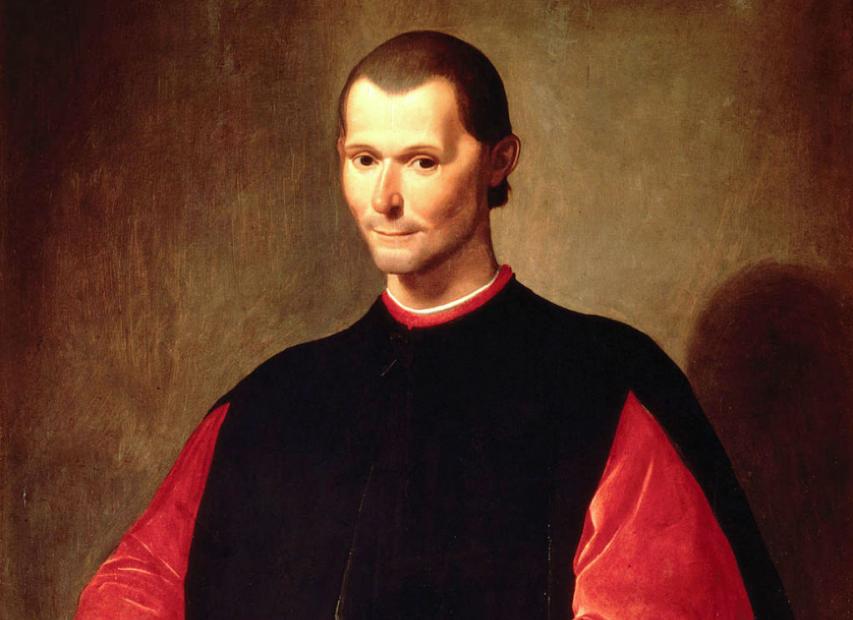

Beside the peculiarities of his patronymic, very little is known about Machiavelli’s early life. He was born in Florence in 1469, at the very height of the Italian Renaissance and, very likely, received the best of humanist educations.

A man of profound culture, then, who soon became a prominent figure in the florentine political panorama. As Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence, Machiavelli was known for his fine diplomatic skills, which he used to the benefit of his motherland in many places in Italy and abroad – let’s not forget that, at the time, Italy was not a unified country, but, rather, a flurry of smaller, independent states, all tied to one another by diplomatic and political relations.

When the de Medicis gained power, in 1512, Machiavelli paid the consequences of his own involvement in the activities of the former florentine republic and, apparently, was even imprisoned and tortured for being suspected of treason against the new rulers of Florence. Soon afterward, Machiavelli decided – or was forced, according to some historians – to retire from diplomacy and politics to private life. It is after retirement that the bulk of his literary production came into being.

Beside Il Principe, or The Prince as it is known to the anglophone public, Machiavelli fathered a large corpus of literature, spacing from poetry and drama, to biography, historiography and works which were to become fundamental for the development of political philosophy, first among them the famous Discourses on the Ten Books of Titus Livy, published after his death in 1531, dedicated to the character and structure of republican rule, and The Art of War (1521) focussing on military strategy and diplomacy.

Towards the end of his life, Machiavelli managed to gain the favours of the de Medicis and was commissioned a History of Florence by Cardinal Giulio de Medici, soon to become Pope Clement VII, the same pope who asked Michelangelo to paint the Sistine Chapel. However, he died in 1527, before gaining full political rehabilitation to the eyes of Florence’s new leaders.

The Prince

A prolific and talented writer, a man of enormous culture and knowledge, Machiavelli is mostly known for the first of his works, The Prince, a politico-diplomatic treaty written in a haste between the end of 1513 and the beginning of 1514. It was to be published in full only in 1532, after its own author’s death.

For anyone who read The Prince, even today, the reasons of its success are clear. Focussing on the figure of a newly established leader and the difficulties related to maintaining power, Machiavelli underlined the essentiality of discerning between personal and public morality and ethics: if the first are essential to govern an individual’s own life and relations with others, the latter are crucial for the government of the state. Such distinction cannot be obliterated nor forgotten, because a good ruler should not lead following personal morality, but considering what is morally acceptable for the well being and safety of the country. And to maintain power solidly within his hands, of course.

Because of this differentiation, Machiavelli justified the idea of necessary violence for the sake of the motherland, hence justifying military intervention and war. By underlining the importance of governing with stability, not only for the sake of the leader, but also for his subjects’, Machiavelli also justified the annihilation of anything – and indeed, anyone – who could represent a danger to the stable and just political status quo of a country.

Extreme ideas, one may say. Yet, once depleted of their most extreme and violent connotations, largely acceptable in the 16th century, but no longer so today, the imprinting of Machiavelli’s thought may well be still visible in how politics work today.

Machiavelli’s in his own words

Machiavellian wisdom for us all.

Niccolò would tell us that “the first method for estimating the intelligence of a ruler is to look at the men he has around him” and that “it is not titles that honour men, but men that honour titles,” placing the stress on intelligence and integrity, both necessary to be a just leader.

On human mind, he wrote: “minds are of three kinds: one is capable of thinking for itself; another is able to understand the thinking of others; and a third can neither think for itself nor understand the thinking of others. The first is of the highest excellence, the second is excellent and the third is worthless.”