Twenty-two years separate the painting of the vault and the painting of the mural entitled the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo was in Rome in 1533, already working on the sculptures for the tomb of Julius II, when he also received the commission for the Last Judgement fresco to be painted on a wall in the Sistine Chapel. Before starting this endeavor, the artist visited Florence for a few weeks, but returned in September: he was to remain in Rome until the end of his life. In the meantime, Pope Clement VII died and Cardinal Alessandro Farnese was elected Pope, taking the name of Pope Paul III.

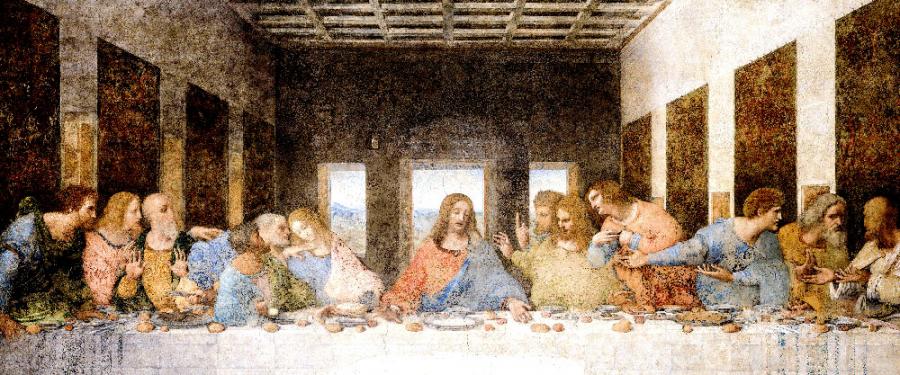

The Last Judgement fresco is on the wall at the altar end of the chapel. Two windows were walled up to form a suitable space for the large fresco. The wall was also prepared at a slight incline, so that dust would not settle on the painting. This time Michelangelo did not divide the space into compartments, like the vault of the chapel, but painted a unique, gigantic view of the afterlife. The fresco comprises a vast whirl of numerous figures with the monumental figure of Christ at the summit of the composition. The Virgin Mary stands at his right side in an attitude of appeal.

At the top, in the architectural lunettes, flights of angels carry the instruments of the Passion. At Christ’s right, beside Mary, are the Patriarchs. In the corners stand the most significant Hebrew women of the Bible. Again, Michelangelo included the pagan Sybils, on the right side; on the left are the prophets, the confessors and the martyrs. The upper part of the painting is filled with the souls of those who have been already judged and deserve to be in Heaven.

Among the martyrs, right below the figure of Christ, are Saint Lawrence (carrying the gridiron of his martyrdom) and Saint Bartholomew. A detail not to be missed is Michelangelo’s own self-portrait, painted on the flayed skin on Saint Bartholomew: one can see his twisted and tormented face. At the sides of the fresco there are vast throngs of souls rising to be judged on the right, while on the left the damned are plunged into Hell.

With Dantesque humor, Michelangelo depicted Minos, the judge of Hell, with donkey’s ears and with the features of Vatican courtier Biagio di Cesena, who had strongly objected to his painting nudes.

The figure of Christ is powerful and awe-inspiring. This is no merciful Christ. His body is massive, looming high, larger that human proportions. He lifts his right hand in a gesture so damning that it is only mitigated by the figure of Mary at his right, appearing to pray and plead. The whole painting represents life after death in an emotional and tumultuous congregation of figures. So awesome is this painting that when he first saw it, the Pope exclaimed: “Lord, charge me not with my sins when You shall come on Judgement Day!”

Just five years after the completion of the painting, with the Council of Trent, the Catholic Counter-Reformation was in full bloom, causing an increase in piety and what appears to us to be excessive morality. The Pope ordered that the nude figures be “dressed”. The painter Daniele di Volterra was commissioned to paint loincloths or breeches on the nudes, and was thus nicknamed “Il braghettone,” the breeches-maker. The breeches have hence been removed.

While the vault of the Sistine chapel fills the viewer with joyful admiration, the Last Judgement, though beautiful beyond description, can also cause a sense of fear and awe. One remains serious and perhaps fearful at the thought of what may await us all beyond death.

With his Last Judgement, Michelangelo changed the course of art in Italy and in all Europe. This huge fresco is the basis and the inspiration for what was to be called the Mannerist style, which in turn was to supply the foundation of Baroque art.

The restored Last Judgement was unveiled in 1993.