Life, we all know it, is truly unpredictable. There’s very little we can anticipate and we rarely think about how, at times, a cheerful, carefree moment with a loved one, a colleague, a family member or even a mere acquaintance, could be the last one we share with them.

When we of L’Italo-Americano received this beautiful interview with professor Mario Mignone, of SUNY Stony Brook, we could not imagine he would not have lived long enough to see it published. His death, which occurred suddenly on the 9th of September, took everyone by surprise and leaves an immense void: in his family’s hearts and souls, without a doubt, but also in those of the many, many students he mentored, supported and encouraged throughout his academic career, as well as in those of his numerous readers around the world, Italy included.

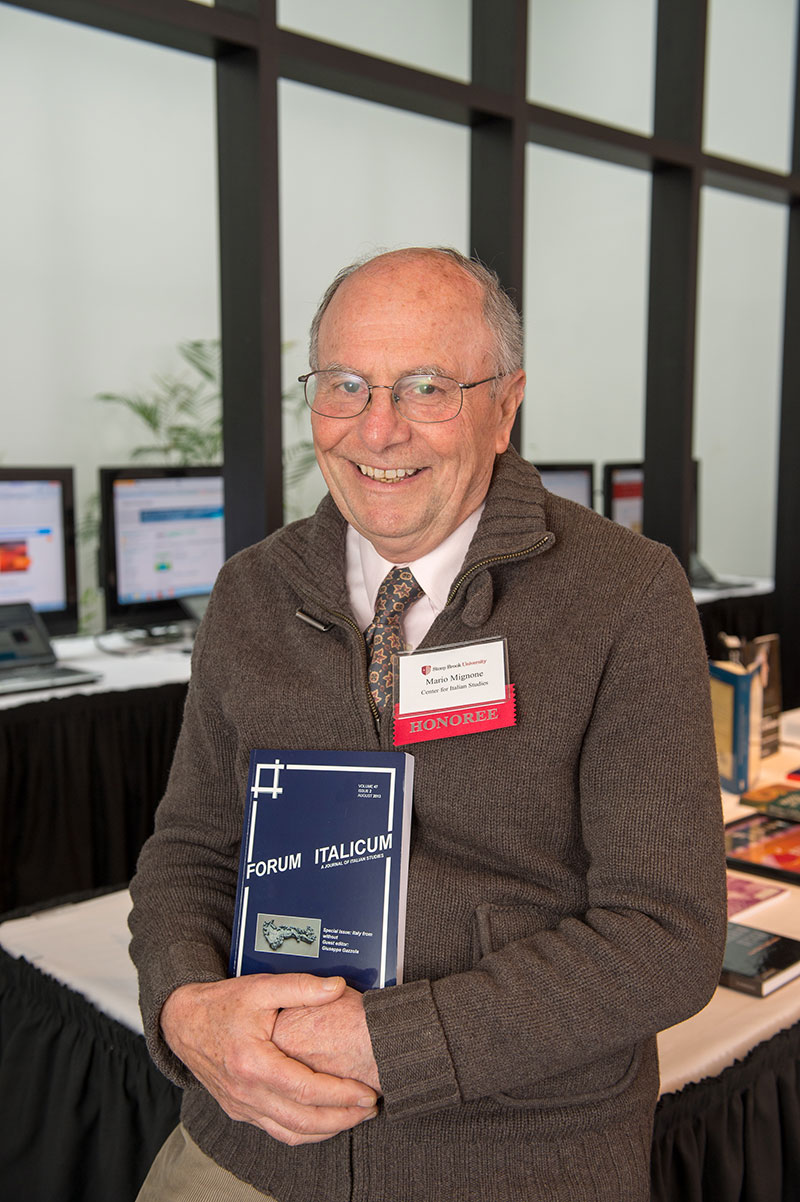

Mignone with a copy of the magazine he directed, Forum Italicum (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

Life and activities at the Center of Italian Studies at Stony Brook University, which he directed, will no longer be the same without his guidance and the time needed to settle back into the prosaic routine of academic life will, certainly, be filled with moments of sadness and hurt: it is always in the simplest of things we tend to miss those we lost the most.

So, it is with even more pride we publish, today, this beautiful interview with Professor Mignone, where he talks about his life as an immigrant, his career and his feelings towards Italy and the US. This is how we wish to honor the life and work of a proud Italian-American and a true inspiration for many of us.

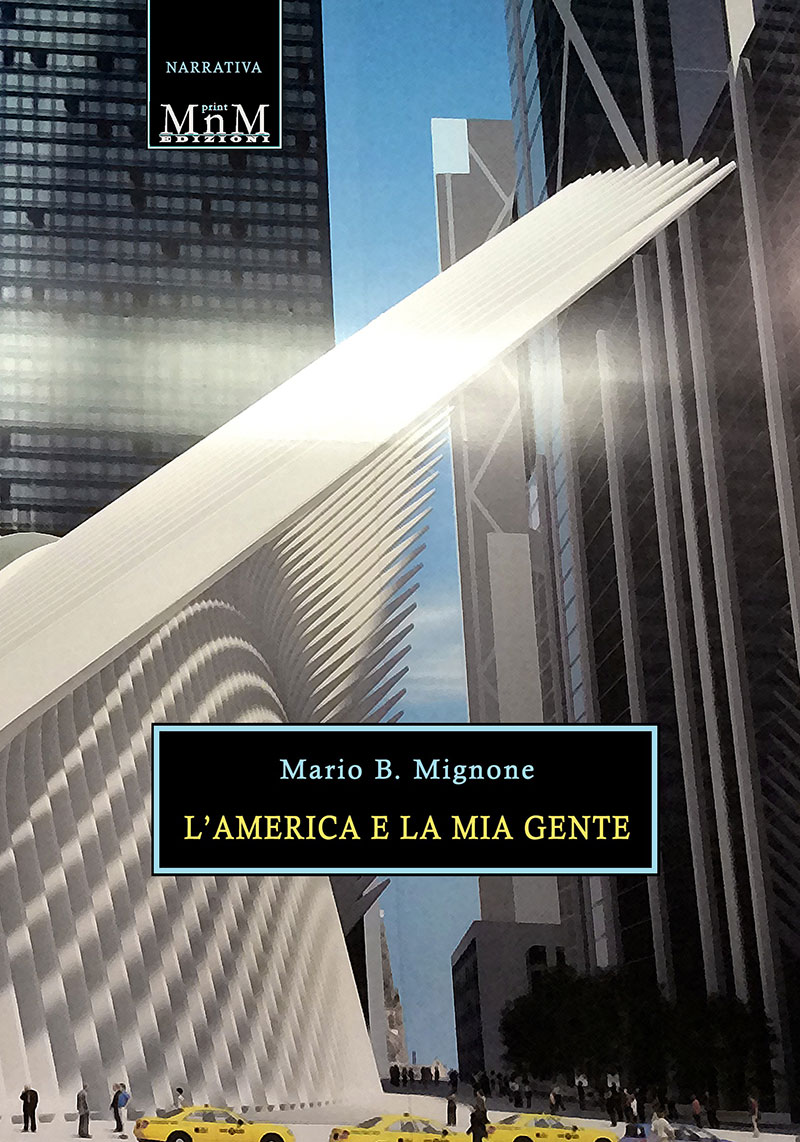

Mario B. Mignone was the Director of the Center for Italian Studies at Stony Brook University where he was also distinguished professor of Italian Studies. He was a celebrated author, whose last book is a fascinating memoir of his journey to America not soon to be forgotten. His vivid, heartfelt and heartening memories were triggered by looking at a family portrait depicting his mother, his brothers and sisters posing in front of Saint Peter’s Cathedral in 1960 in Rome, before collectively taking a DC-8 to New York. L’America e la mia gente is published in Italy by MnM print edizioni, while an English version, entitled The Story of My People – From Rural Southern Italy to Mainstream America was released in New York by Bordighera Press.

Mr. Mignone, who was born in San Leucio del Sannio, a small rural village less than four miles from Benevento, has had an impressive academic career in the United States. I recently had a conversation with the eminent Italian-American professor.

Mario Mignone in Rome with his students (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

Professor Mignone, can you describe the specific emotions associated with the moment of departure? Your parents bought you new clothes to wear that memorable day.

The departure of any emigrant is never a happy occasion. Even though we had been waiting for six years for that moment, it was difficult to say goodbye to so many people who were dear to us and to detach ourselves from all those places and things so familiar to us and to which we were connected. Unfortunately, I had witnessed the departure of many emigrants, some very close to me. Many times I underwent the loss of friends snatched away by the emigration process, yet it never became routine: new departures, new loss, and pain. And then, it was finally our moment to cut the umbilical cord and depart for the unknown.

Mignone family in America for only three years and very happy on the day they come to live in the building they bought (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

When you arrived in New York, you found a job as a factory worker four days after your arrival. You didn’t speak the language but your very determined aunt Flora helped you find a paid position: you were hired by Hertlein Special Tools Co., beginning what you call “my baptism in the American productive system.” Thanks to that humble job that provided you enough money to support your family, you could attend evening English classes at Roosevelt High School and then enter City College (CCNY), the first university to offer free college tuition in the United States.

I did not have the luxury of looking for the job that I liked. I needed a job as soon as possible to help support my family; my family of eight could not abuse the generosity of my grandparents for too long. It would have been irresponsible for me, the oldest sibling, to search for the dream job!

A close-up of the late Italian-American professor and writer Mario Mignone (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

You built the whole story around specific moments of challenge, change and growth.

We emigrated when the Western world was going through profound social and cultural transformations, which I reference in the book. I framed my personal story and that of my family in the historical, social and cultural context of the early 1960s, years of social engagement. In 1960, although Italy was enjoying the “economic miracle,” we did not feel the effects of it in the South, and were migrating either abroad or to the Italian industrial triangle by the thousands. I was determined that in one way or the other I was going to leave, just the way many other thousands of people in our area had been doing. I was not going to wait and see if the effects of the “miracle” were eventually going to trickle down south and provide some form of employment. I did not believe in that kind of ephemeral hope.

L’America e la mia Gente

Once you arrived in the States and first settled in the Bronx, your uncle Gelsomino told you: “well, in America you will make it only if you work hard. The word ‘work’ is the only key to success.” Is that still valid today?

Yes, it is still valid, and it will always be valid. Naturally, we don’t mean necessarily physical work. My father used to say, “You cannot take a short cut to complete a task because eventually your work will not stand out.” Skills, passion and commitment are the ingredients to success.

You wrote that your father spoke and acted like a character by Sicilian realist (verista) writer Giovanni Verga named Padron ’Ntoni, a man strenuously faithful to the ideals of honesty and hard work. Did your father play a big role in teaching you a sense of duty, responsibility, and endurance?

I certainly had my father as a model. He had worked hard all his life on the farm. His actions were my lessons.

You always felt great affection for your grandfather as well. He moved to America in 1906. He lived a life of sacrifice and could eventually buy some apartments in New York. He laid the groundwork for your family’s future successes. Your cousins moved to New York in 1954. Six years later, you, your mother, your brothers and sisters joined in.

I have always had great respect for him and the emigrants of his generation because they moved to a world that, in many ways, was still cruel, unjust and permeated by the pain of discrimination. Those emigrants, faceless people who never received the respect and even the attention they deserved for their contributions in pouring the foundations of America and for enriching Italy through their remittances, are truly my heroes. In the case of my grandfather, it was because of his significant sacrifice of working hard and saving his meager income that his children and grandchildren felt a sense of security when they came to America.

The Mignone family with friends in front of St. Peter’s Basilica on the day of their departure to the United States, Rome 1960 (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

You wrote that growing up on a farm in Southern Italy made you acquire a sort of stoic attitude. Did you learn how to be more resilient and adapt better in the US?

Even though my siblings and I were going to school, my father kept us fully engaged in farm life on a daily basis. We had assigned tasks and responsibilities to fulfill. In the summertime, our work on the farm became more involved and more demanding. Some of the work was quite heavy and harsh. Consequently, when I came to the US and found a factory job working 10 hours a day, frankly it was not an impossible task. I certainly would have preferred a lighter job, possibly working in an office. However, that experience toughened and prepared me to overcome obstacles with less stress. I say in the book that “the hardest steel comes from the hottest fire:” the metaphor is very true for life experience.

Professor Mario Mignone (Ⓒ: Stony Brook University)

When you arrived in NY, “It was also a new era for Italianness,” starting from the multitude of Italian-American singers who dominated the music scene with their melodic voices.

The Italians also played a “decisive role in the American Civil Rights Movement.” You remembered Monsignor Geno C. Baroni who became the coordinator of the March on Washington when Martin Luther King delivered the exalted “I Have a Dream” speech.

The emergence of Italian Americans was part of the social and cultural transformation of America. Many young Italian Americans fought in WWII with some volunteering to show allegiance to the US. When the war was over the GI Bill, which made college education free for war veterans, helped thousands of Italian Americans pursue a college education and break down social and cultural barriers. Eventually, they also deflated many stereotypes that their fathers and grandparents had to endure. In large numbers, they entered the middle class and became part of the mainstream, and in some parts of the US, like Long Island, New York, where my university is, they directed the stream. One of the many tangible pieces of evidence of that success is that on Long Island every public high school introduced the teaching of the Italian language, often due to community pressure.

[/caption]

I perceived bitterness in your words when you talked about the younger generation of Americans, “teenagers covered with tattoos who isolate themselves from the world and demand subsidies from the government”. You are a teacher. How do we teach kids responsibility, respect and work ethics?

We have seen a profound cultural change in the way my parents and people of my generation related to children, to institutions and society in general. Today there is a strong interest in protecting individual freedom, privacy, identity and diversity. It could be a wonderful way of living, but we need respect for laws and order accompanied by a personal sense of responsibility to maintain and improve our civil society. Teachers require authority and the respect to teach ethic values. Freedom of action and speech cannot exist in an absolute sense!

The statue of Core Contento symbolizing the serene and placid living in the Terre Sannite. Photo credit Pro Loco san leucio del Sannio Adriano Zuzolo

You wrote that poverty is also a state of mind. “We had pride, a sense of self-esteem, decorum and determination to succeed.” You never felt poor. And you added: “Paradoxically, we had to become poorer to become richer.”

In Italy, we lived on a farm that my parents owned. My father claimed that the Mignone family had always lived in their own house and owned property. In America, we started from ground zero. Yes, we had less than we had in Italy and in a way we were poorer. Nonetheless, we never felt poor because we sensed that with work and collective family cooperation we would acquire social status. In fact, after three years in America, we bought a building with five apartments. The Chinese, Indians and Koreans who form the new wave of immigration are following the same road to success. Many immigrant students in my classes at the university, who read the book said that my story in was also their story.

What would you suggest to a young Italian today who cannot find a job in Italy? Be more resilient in your home country or pack and leave? What about leaving for the US today?

Today many young Italians are moving out in the world with many achieving success. In fact, there are many young Italians employed as researchers at my university. I have met a number of them working in various fields and most are full of energy and eager to prove themselves in their careers. But I do not suggest that everyone should pack up and leave, not at all. However, if various attempts at finding a job in Italy, and not necessarily the ideal job, have failed, then I might say leave, but be prepared to face huge obstacles and have faith in human strength, imagination and creativity.

Today I do not feel the same collective energy that was propelling the US into the future in the ’60s. However, there is almost full employment here and some companies are struggling to find qualified personnel. In my huge family, my children, my nieces and nephews, the first generation born here, are all doing well, some extremely well and they did not have to struggle to assert themselves. Yes, they are the children of immigrants who still have that strong desire to achieve in American society, yet the opportunities are still those of the ’60s if one understands the changes that technological advances have created and the employment needs in our society.

Your journey back to your childhood with your wife and your daughters was what you expected. You wrote it confirmed “Heraclitus’s old saying: ‘you never bathe twice in the same waters of a river.’” Do you experience nostalgia for a time in Italy that you have never known as an adult?

The problem of the emigrants is confronting the changes that have occurred in their place of birth. It is the problem of Anquilla, the protagonist of La luna e i falò by Cesare Pavese. The return home may be traumatic: the birthplaces have changed, sometimes profoundly, and the emigrant has also changed profoundly. Thinking we will find our former homes the way they were when we left can be unrealistic and ultimately painful.

What is your current relationship with Benevento and the Beneventani?

I love to go to Benevento, but my ties are mainly sentimental with no relationships with institutions or organizations. Many years ago, I tried to create a student exchange between my university and the university at Benevento, but I did not succeed. I had established four exchanges with other universities in Italy, but I did not find interest in Benevento. However, I am very excited about an upcoming visit to our local high school and my university by a group of students from the Liceo Classico “Pietro Giannone” in Benevento. I am working hard to make the visit memorable for the students of Benevento.

“The kitchen was the altar of my mother,” you wrote. It was a place where your mother, through food, healed your body and soul, a space of protection against “the street wolves.”

Mothers had fundamental roles in Italian families. That role was the glue for the unity and success of my family. My sisters and some of our wives still try to carry out that role. Italian dishes are the main food in our families, but it’s the role of the mother, also through the dinner table, to keep the family together and energize it. Without the security my mother created at home, I doubt that of her eight children three would have become doctors, one a dentist, two university professors, and two public school teachers.