When Italians found their way to the Pacific Northwest at the beginning of the 20th century, it was often to work in the coal mines, help build the railroads, or take on “pick and shovel” work as part of a construction crew. Some were tenant farmers hoping to save enough to buy their own little piece of paradise.

The great wave of Italian immigration, which began in the 1880s and lasted until 1920, brought more than four million Italians to America. About 75 percent stayed on the east coast, in cities such as New York, Boston or Baltimore. Less than one percent of Italians living in America made it as far west as Washington state by 1910.

That year, Seattle was home to the state’s largest number of Italian settlers – nearly 3,500. About half of them lived south of downtown in north Rainier Valley and north Beacon Hill, choosing neighborhoods that had been settled earlier by German immigrants. It wasn’t long before locals started calling the area Garlic Gulch. It was Seattle’s version of Little Italy.

The early Italian immigrants tended to congregate around others from the same village or region in Italy. This way, they could speak their own regional dialect, eat familiar foods, worship at the same services, and access a network of friends and relatives who could help them find housing or a job. Garlic Gulch was home to people from both the south of Italy – primarily Naples, Calabria, and Abruzzo – and from the north, including Milan, Turin, and the many small towns of Tuscany. Notably absent were those from Sicily, who tended to stay on the east coast.

In 1915, Rainier Valley was like a small Italian village with about 215 families. Everyone knew everyone else. Vegetable gardens were everywhere and families often made their own wine at home.

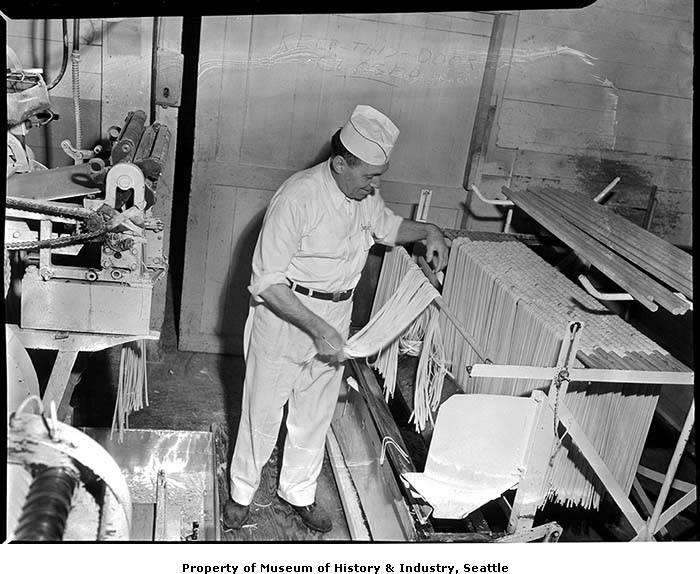

Just about everything a family needed could be found in Garlic Gulch. There were Italian grocery stores, pharmacy, barbershop, meat market, bakery, and macaroni factory. The Vacca brothers sold their fresh vegetables at a produce stand. The new Italian Café was a popular meeting place with game tables in the back, and a building nearby housed an Italian-language school.

Many well-known businesses and brands got their start in Garlic Gulch; some were in business a century later. A few are still run by family members while others were bought out by larger conglomerates. The list includes such iconic brands as Oberto’s Sausage Company, Big John’s PFI, Isernio Sausages, Merlino Foods, and many more. Their stories are examples of hard work, dedication, and determination to succeed.

Several prominent politicians also grew up in the area. One of the most well-known was Albert D. Rosellini who served as Washington state governor for two terms. His cousin Victor, a famous restaurateur, launched several elegant Seattle restaurants that were frequented by the movers and shakers of the era.

Our Lady of Mount Virgin Catholic Church saw to the spiritual needs of the community. The church, which overlooked the Italian neighborhood in Mount Rainier, was built on the site of an earlier wooden church erected by the German Catholic community in the 1890s and named for St. Boniface. As more Italians poured into the area, they initially shared the building with the Germans but soon the Italians wanted a church that reflected their own heritage and language.

Father Ludovico Caramello, an energetic Jesuit priest from a well-to-do family in Turin, Italy, was assigned to the parish. A new church opened in 1915 and a small parochial school nearby opened in 1918. The school, run by the Dominican sisters of Tacoma, remained open for 60 years. Fr. Caramello would visit the school every week to teach Italian. Eventually, the smaller St. Boniface was decommissioned and served as a parish hall.

This past summer, citing dwindling attendance, a shortage of priests and rising costs, the Seattle Diocese decided to merge Our Lady of Mount Virgin with another parish, but those details have not yet been finalized.

Urban expansion sounded the death knell for Garlic Gulch. It did not come all at once but arrived in several waves. In 1940, the state built Interstate 90 which sliced through the Italian commercial district in North Rainier and tunneled through the Mount Baker neighborhood to reach Lake Washington. Twenty years later, Washington wanted to widen the highway from four lanes to ten. Although the expansion was tied up in the courts for years, many residents saw the writing on the wall, sold their homes, and moved elsewhere.

The recession of the early 1980s did not help. Crime increased, mom-and-pop businesses closed, and trash-filled lots proliferated. In the 1980 census, the city was home to 6,248 individuals of Italian heritage, or 1.3 percent of Seattle’s population. The largest portion of those – just over 1,000 people – still lived in Garlic Gulch.

As new immigrant groups arrived in the Northwest, the demographics changed yet again. The area became home to Vietnamese, Laotian, Chinese, Latinos and East Africans. By the early 2000s, the streets of Garlic Gulch, once fragrant with the smells of Italian cooking, are redolent with the aromas of Mexican cantinas, Vietnamese pho shops, and Ethiopian restaurants. The melting pot that is America continues to evolve.