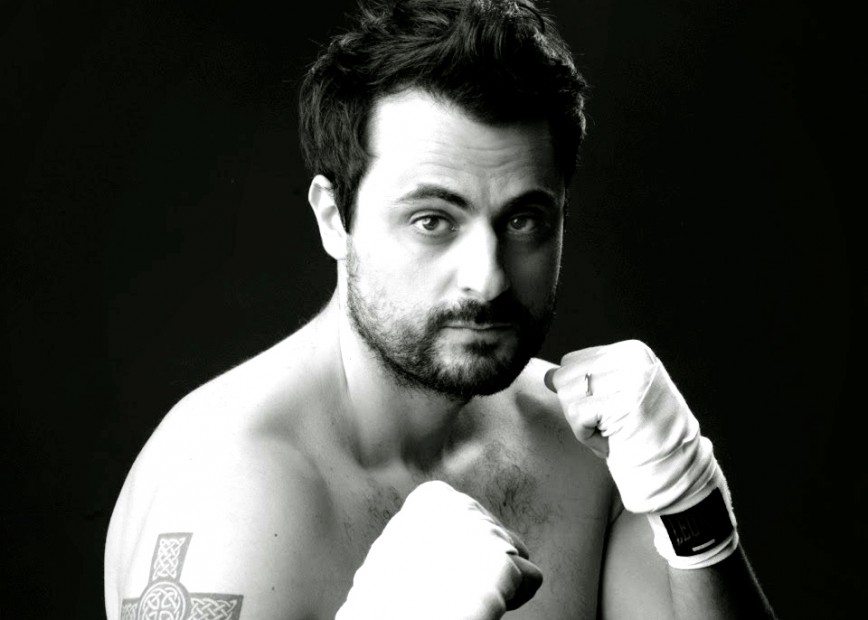

Gabriele Tinti is an Italian poet and writer, whose poetry has been extensively inspired by the ancient-art form of boxing. He is moved by solitude and tragedy, which inspires him to write rhymes that have been presented at the Queens Museum of Art, the New York Poetry Festival, South Bank Centre and the Museo Nazionale di Roma.

He will be coming to Los Angeles, to the Getty on Aug. 3 with Italian-American actor, Robert Davi for The boxer, a reading tribute to the famous Greek sculpture, The Boxer at Rest (il pugliatore a riposo) that is currently on loan from Rome for the ‘Power and Pathos exhibition’. This capolavoro is dated back to 4 A.D., but it was intentionally buried to preserve it against invasion, therefore was not discovered until 1885. It first came to American shores via the east coast in 2013, and shall be making its Pacific coast début for the first time next month.

The Boxer at Rest has inspired two of Tinti’s poems, and the afternoon will be followed by more of Tinti’s poems at the Italian Cultural Institute in Westwood, which has organized both events. Tinti and Davi became acquaintances through their mutual friend, actor Franco Nero, and are united by their passion for boxing.

Tell me about yourself. Where did you grow up and where are you based now?

I live in the same place I grew up, in a small seaside town (Senigallia) in central Italy. I have always felt an immense solitude here. If I had been born elsewhere, I probably wouldn’t have written a single line. There is something in the Marche region – in its sky, its humor. It has the capacity to put you in contact with the tragedy of our existence. It’s no coincidence that this is where Leopardi used to live.

Some may see it as an unlikely marriage – the combination of poetry and boxing, what prompted you to combine these art forms?

Boxing is poetry; it’s art. It’s a dramatic arena of solitude and the boxers are more than just “athletes.” Their lives are lived to the limit, founded on risk. They represent one of the most authentic spectacles of suffering a human can participate in.

What is your relationship with”? What emotions does it evoke within you?

The unearthing of the Boxer in 1885 on the slopes of the Quirinal Hill in Rome sparked great debate. The statue was discovered near the ancient baths of Emperor Constantine, and more than a century later, the debate still continues. No one knows exactly who created him, or what he represents. Nonetheless, the thing that matters to us, the thing that has always drawn us, is the “transcendent fatigue” which seeps out of the statue. The artist shows the boxer in the act of turning his head whilst something significant is happening, this is what the ancient Greeks would refer to as the Kairós moment – the right, opportune, supreme moment to act. The boxer is sitting, marked with deep wounds and copious amounts of blood that cover the whole right side of his body. We do not know why he is turning his head: perhaps he is listening to the decision of the judge? Or is he hearing a new call to combat? Is he looking at the agitated crowd? Perhaps he is uttering a silent prayer to Zeus, waiting for the answer? Standing in front of the Boxer, I couldn’t do anything besides summon the fragility, the solitude, and the weight of the boxer’s dramatic life. After all, each time one seeks to analyse a profound work of art, one comes face to face with its irreducibility. Poetry should never have to reduce itself to an explanation. True poetry always travels beyond every calculation, every system, every geometry: it’s incomplete, evocative, and lamenting.

At the turn of the 20th century, boxing was revered all around the world. The title of the emperor of masculinity was coveted more than anything else. Does modern boxing hold the same allure for you as boxers of the past?

Boxing has certainly become less “popular” than it was, what with the exclusivity of its broadcasting with pay-per-view (HBO and Showtime). However, since Premier Boxing Champions (CBS) has begun to broadcast boxing for prime time television, things are clearly changing. More than anything though, it’s the boxers that count. Boxers – with their courage and fragility, their will for tragedy. They are the same today as they were one hundred years ago. You don’t need to go far back to find the drama or the poetry that boxers so easily inspire. I think immediately of Arturo Gatti’s story or more recently, of Paul Williams.

What are your thoughts on Jack Johnson, and why did you choose him as a subject for the webcast you did on Rai3?

Jack Johnson’s story is a story full of exertion, desire, downfalls and glory. His story was fundamental for the awakening of black conscience and pride at a time when the champion of the world was reserved for the strongest man in the world. In America, the champion boxer used to be the most important person, more highly esteemed than any president. His story is important, because it speaks freedom and courage.

Jack Johnson referred often to the ‘science’ of boxing, and you intern talk of its mysticism. What do you think makes boxing more than just a sport?

Boxing has the same creativity and symbolism as dance, but with the emotion, passion and reality of conflict. This intensity of meaning makes it something extremely special and absolute, hence why Walter Pater called it “one of the fine arts”. However, I think that it’s even more profound and captivating than the fine arts, because it is not determined by words. The disciplines of fine arts (theatre, music, literature, performance) are fictional, representative and evocative in the best of cases. Boxing embodies all these things, but it has something else, which is fundamental – reality – with its spasms, pain, bloodshed, unpredictability, and its escape into a predestined plan.