More than 200 years after it was invented, the elegant Bodoni typeface is still among the most admired and largely used around the world. Indeed, it is easy to come across the Bodoni font on a daily basis; it is a favorite of high-end fashion labels (think Valentino, Armani, Calvin Klein, Guerlain and Vogue), and is widely used in posters, logos, displays, headlines, and of course books, newspapers and magazines.

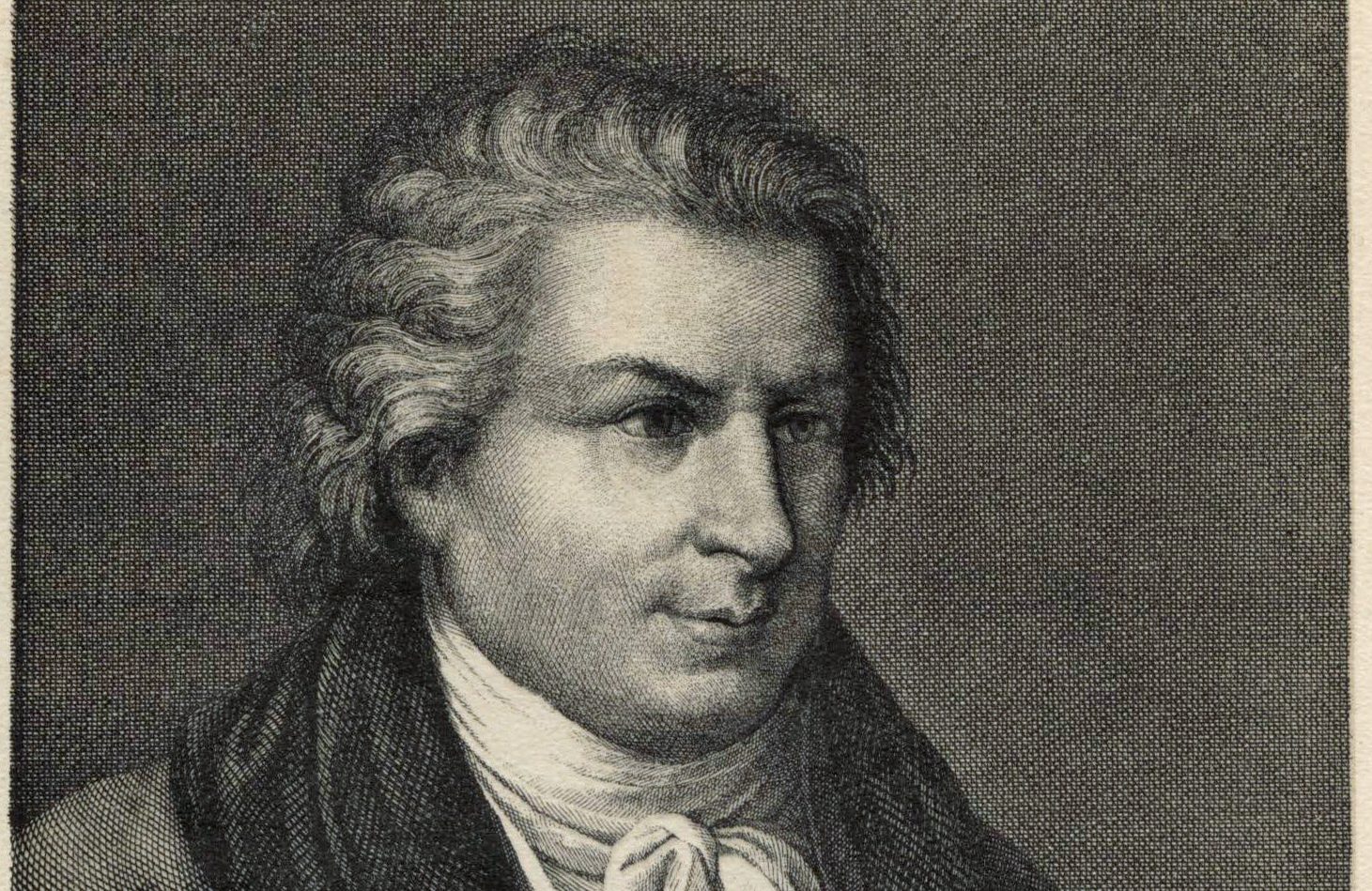

So, who is behind it? An Italian by the name of Giambattista Bodoni, who lived between the 18th and 19th centuries, and achieved a “rock star” status in the world of typography at a time when the printing profession was highly regarded.

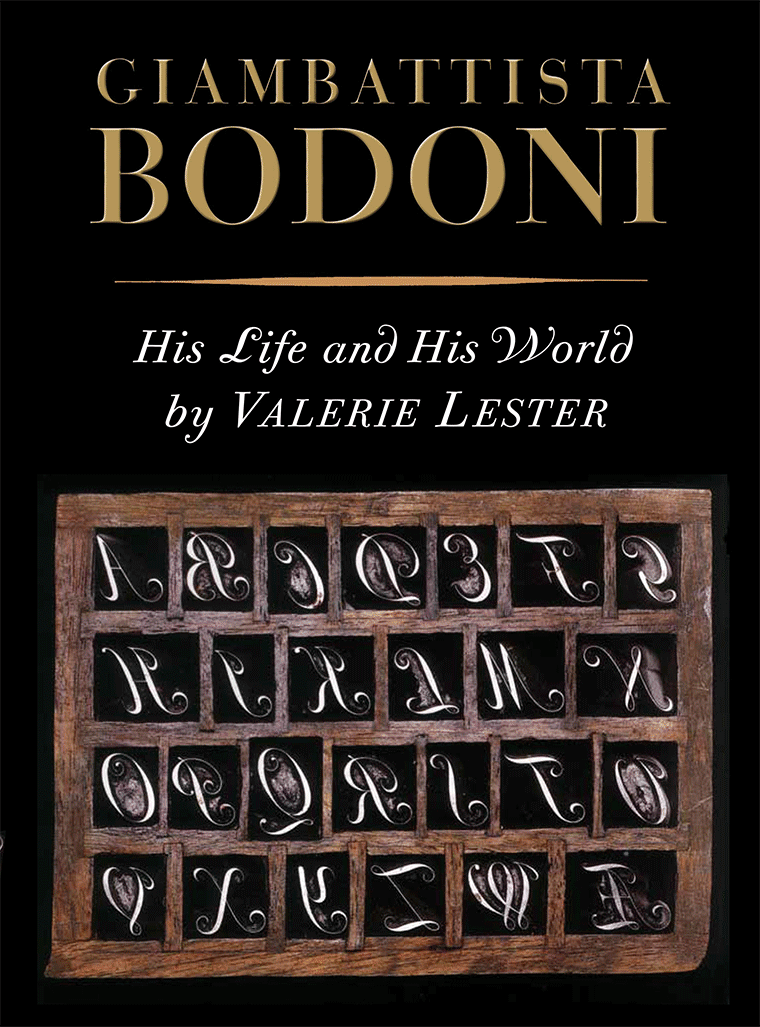

A recently published biography, Giambattista Bodoni: His Life and His World (Godine, 2015), the first in English dedicated to the Italian typographer, type-designer, printer and publisher, explores the life and career of a man, or rather, an artist, whose legacy is very much alive – with most people ignoring it. “I hope my book will open the eyes of British and American readers to the life of Giambattista Bodoni, and that they will see him as much more than a typeface,” said the book’s author, Valerie Lester.

The way Lester became interested in the topic is decidedly unusual, as she first heard the word Bodoni at a dinner party in California, when her host mentioned he inadvertently owned a stolen book, which he must return to the university from where it disappeared. The book was Bodoni’s Manuale Tipografico.

“He showed it to me and from that moment I was hooked by the idea of introducing Bodoni to English speakers, who until then had only known Bodoni as a typeface,” Lester recounts. “I was also intrigued by the idea of doing research in Italy, in the three lovely places in which Bodoni lived: Saluzzo, Rome, and Parma.”

Giambattista Bodoni was born in 1740 in the Piedmontese town of Saluzzo, in the foothills of the Alps. His father and grandfather were both printers, so Bodoni was exposed to the profession early on. He quickly showed a natural penchant for wood-engraving and printing. His ambition brought him to Rome at the age of 17; he was determined to become the greatest printer who ever lived.

In Rome, Bodoni served as an apprentice at the press of the Propaganda Fide, the missionary arm of the Vatican. There, he learned the art of punch cutting and refined his skills as a compositor and designer; he specialized in designing and engraving Middle Eastern and Asian characters, demonstrating a gift for exotic languages, which soon had him promoted to be the press’s compositor of foreign languages.

After eight years in Rome, Bodoni was eager to further refine his skills and decided to travel to England to learn firsthand from John Baskerville, a printer and type designer who Bodoni admired and followed. His time there was brief though, as he fell ill and was forced to return to Saluzzo to recover.

By then, Bodoni had already acquired a certain fame; thus, when Duke Don Ferdinando di Borbone, who ruled the city of Parma in Emilia-Romagna, decided to open a royal press (Stamperia Reale) to compete with those of other cities, Bodoni’s name came up.

Bodoni moved to Parma in 1768 and spent the rest of his life and career there. He set up his home and business in an outbuilding of the magnificent Palazzo della Pilotta complex (which now houses a museum dedicated to him, the Museo Bodoniano). The task at hand was big, but his ambition bigger: he acquired all the tools he needed to create a printing business of the highest order and gradually developed his own style, achieving an unprecedented level of technical refinement.

He produced Italian, Greek and Latin books, and printed materials for court use. His first major publication at the royal press was a volume in celebration of the wedding of the duke of Parma to Archduchess Maria Amalia of Austria, Descrizione delle Feste Celebrate in Parma per le Auguste Nozze; in its genre, it remains unsurpassed in its beauty and printing technique.

By 1790, Bodoni had become widely known; his work was sought out by collectors (it still is), and important people wanted to meet him. Benjamin Franklin wrote him a fan letter and Napoleon was so pleased with the gift of Bodoni’s Iliad that he made him a Chevalier of the Order of the Reunion and gave him a pension for life. “Bodoni lived in turbulent times, but was surprisingly unaffected by them,” Lester explains. “He was ambitious and self-absorbed. He allied himself with whoever was in power, whoever would support him. […] His fame as a printer became so widespread that the rich and famous of Europe flocked to his printworks, eager to meet him and to purchase beautiful books printed by the greatest printer of the age.”

Bodoni’s masterwork, Manuale Tipografico, was published posthumously in 1818 by his much younger wife Margherita, whom Bodoni had married at the age of 51. Other Bodoni masterpieces include Oratio Dominica, a reproduction of Pater Noster in 155 languages and 215 different fonts; the Iliad’s 1808 edition, still considered the most beautiful ever printed; and all the Latin, Greek, French and Italian classics, at once and to this day coveted by the most important libraries of the world.