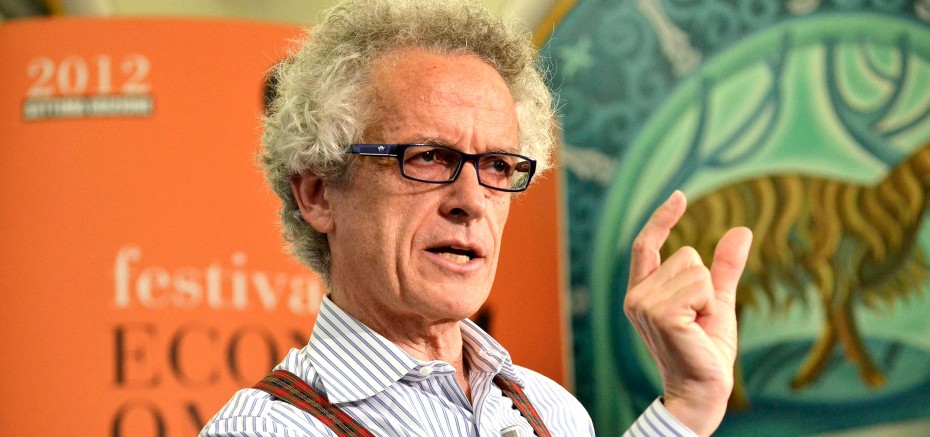

It wasn’t a tweet that kicked off the life long career of Federico Rampini. The award-winning Italian journalist is no over-night 140-character sensation. After all, he recently followed President Obama in Antalya, Turkey, and covered the G20 summit, which focused on the recent Paris terrorist attack and the best way for the international community to defeat Isis.

Before covering events like this and having the impressive array of articles, essays and books now under his belt, Rampini first reported using neither a computer nor a cell phone. Back in 1977, when he started in Rome, even “the fax machine was a novelty,” he writes answering my question on how much journalism has changed since then.

“When I was assigned to Romania in 1989 to cover the democratic revolution that toppled the Communist Dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, there was only one hotel in Bucharest for the foreign press and we literally had to fight for the very few international phone lines. Once we had written our stories we had to read them on the phone to our headquarters,” Rampini writes.

Funny scenery thinking of the year 2000 when he was sent to San Francisco as a correspondent to Italian newspaper “La Repubblica” to follow closely the New Economy, or “the first Internet revolution, when the access to the web was becoming universal,” as he specifies during our email interview.

Ever since that move, Rampini has made space for stars and stripes in his tricolored heart.

Currently based in New York City, he is writing about the next presidential elections, and the latest television debates among the candidates. The Federal Reserve and the next move on interest rates, writes Rampini. “At the end of November I will follow Obama again, for climate change summit in Paris.”

Paris. Full stop.

Answering my last question on what changes he wishes to see both in Italy and the United States, Rampini leaves me with the following words: “right now, the main wishes for my two beloved countries are very similar. To defeat terrorism. And to build a new model of economic growth, with less inequalities and a fair access to opportunities for all,”

In what way do you believe the Italian-American community has changed in the last decade?

Always for the better: smarter, wealthier, more successful, more influential and powerful community. Right now in New York City we have an Italian mayor and in New York State we have an Italian governor. All over the nation I see new generations of Italian-American entrepreneurs, scientists, artists. There would be no American cinema without Francis and Sophia Coppola, Bob De Niro and Al Pacino, Turturro and so many others. My favorite ones are the Italian-American scientists who are working on genetic research to defeat brain diseases, like Alzheimer and Parkinson. I also notice that there is a deeper interaction between Italian-Americans and Italian nationals, who work here. The landscape of New York City is being changed for the better by the work of the greatest architect in the world, Renzo Piano, who designed the New York Times building, the Morgan Library, the new Whitney Museum, and is now creating the new Columbia University campus.

Having always lived in international and multicultural environments, why do you think Italy struggles so much to accept immigrants, when it has been a country of migrants for centuries?

As a matter of fact, Italy today is much more diverse and multi-ethnic than when I left 15 years ago. Whenever I go back to Italy I see Chinese, or Filipino, immigrant children who speak perfect Italian, sometimes even regional dialects. The Italian public school system is doing a great job to integrate them. Yes, there are worries and resistance, because mass foreign immigration is a more recent phenomenon in Italy. Also, tragic events like the terrorist attack in Paris amplify the fear linked to Islamic extremism that may take roots in the immigrant communities of Muslim faith. It’s a complex problem. These communities, as President Obama said in Turkey, must lead the fight to insulate and defeat the extremists. They haven’t done enough until now.

You watch Italy from New York daily. What do you believe are Italians not seeing?

Italians are seeing… too much of New York. I mean, the average Italian grew up watching US-made movies, listening to American music, following as a teen-ager a mostly American dress code, buying iPhones and iPads, and so on. US-made mass culture has had an enormous influence on the rest of the world, Italy included. So there is a tendency to have an idealized vision, full of stereotypes, both good and bad. Many Italians tourists come to New York believing it is the center of the world – which is probably true – but they also tend to see it through the lenses of all the commonplaces they have accumulated back at home.

In what way do you still feel connected, and proud, of being Italian? And in what way you don’t?

I feel very connected and very proud. First of all, although I left Italy more than 15 years ago, I travel there very often. Nowadays I would say that on average I go back to Italy every other month: for a book-tour, a theater performance (I do theater too), a conference, etc. So I never really “dis-connected”. Moreover in my life in the US I tend to have lots of Italian friends, in San Francisco and in New York. I eat Italian food. I go to the Metropolitan Opera. I speak Italian to my Italian wife. Who wouldn’t be proud to be an Italian? Of course I am ashamed when I read about corruption scandals, and there have been quite a lot recently. Also, I believe that the economic situation is still weak, which is why so many young Italians come to the US looking for a job.

Silicon Valley hosts many Italian talents that often end up staying there. How much longer can Italy afford to lose its best intelligence? What could the country system do to become more attractive?

I have many young Italian friends in the Silicon Valley. First of all, I don’t think they are “lost” forever. Some of them, after having a successful experience in research and innovation, after creating their own start-ups, sometimes will invest back in Italy. Today the geographical location of your company doesn’t mean that you’re stuck forever in a specific country. Of course Italy has many things to do in order to create more opportunities for our young people. The most important one we call meritocracy. I hear lots of young Italians complaining that they could not get a university job or a research assignment because the son, the daughter, the nephew of some powerful “Professore” got an unfair advantage in the selection process. Bureaucracy, over-regulation, are also mentioned as obstacles, as well as the slow pace of civil justice, which means that if a customer or business partner doesn’t pay you what they owe you, you might wait for years before the justice system will settle the issue.

Since you taught at U.C. Berkley, where do you think the National Academy System lacks in order to be competitive?

My university experience is very limited. More than a decade ago while living in San Francisco I was occasionally a visiting professor at UC Berkeley, both for the Italian Department and European Program (I taught a seminar on the European Union), and also at the School of Journalism when Orville Schell was the Dean. Afterwards while living in China I had brief experiences as a visiting professor at Shanghai University of Economics and Finance. More recently I have taught at seminars and webinars at the Bocconi MBA in Milan. But it’s not my main job, and I spend too little time teaching, for me to be able to compare different systems. I believe that Italy has excellent universities, and I can say it on the basis of evidence: young Italians who come to the US are very successful, they receive scholarships, they get research grants, they are hired by the best US universities. It’s a reward for their talent, of course, but they must have received also a good education back in Italy.

Starting with the idea of collective sharing, we have now arrived to personal data control. Just a few days ago, Tim Cook ironically said: “privacy is endangered” at Bocconi University. Where is this leading us?

Tim Cook should know. The company that he leads, Apple, is actively endangering our privacy. Same as Google, Facebook, Amazon. You name it. They are all in the business of stealing our personal data in order to market their product to us, and also to re-sale those information to others. I have written a book on this issue, it’s “Rete Padrona,” a title, which you could translate as “The Masters of the Web.” It’s also an autobiographical book: I compare the libertarian and egalitarian dreams of the Silicon Valley that I knew 20 years ago, to the reality of today’s digital behemoth. They have re-created a very unfair capitalistic system, with the same inequalities that we tended to associate with the Old Economy, Wall Street.

It is often said that China is in contraposition to the United States, which raises the fear that the two countries opposing interests may lead to a potential WWIII. Having lived in both realities, do you believe this scenery is possible?

In the long term there will be a growing rivalry between the incumbent superpower and the emerging challenger, I have no doubt about that. But China until now has shown some restraint at least in the use of military power. They have fought “only” four wars since the beginning of the People’s Republic (1949): in Tibet, Korea, India and Vietnam. The last one was in 1979. There has been no Chinese military intervention for 36 years. China will challenge the American leadership in many ways, but war is not inevitable.