For Christian Catholics, Holy Week is the most spiritually pregnant moment of the year, even more than Christmastime. But in Italy, this is a time resonant with meaning among people who don’t believe, too: Holy Week is a time of traditions, of history, of communities coming together not only within the meaningful — for those who believe — embrace of religion, but also under the immense and beautiful sky of tradition. Full communities rediscover to be such, unified by an ancestral sense of belonging, and connection with one another and with their past.

We’re about to enter days made of faith and history, then, but also of loving memories of childhood, when for the first time we had attended processions, masses in Coena Domini, and Saturday night’s Easter Vigils, more often than not holding the hand of our grandparents: strong and gentle, they were, present and discreet, themselves the symbol, when you think about it, of that very link between past and present, sacred and profane, pragmatism and carefreeness that makes so much of Italians’ own identity of today.

During Holy Week, the members of Fraternities in Taranto carry the statues of the Stations of the Cross, wearing a white robe and a white hood © Francesca Sciarra | Dreamstime.com

And so, we learn about confraternite and their powerful, unifying role in so many communities of the Belpaese. How could we explain what they are, to those who’ve never experienced their presence, nor seen them standing in the pews, all dressed the same, all proud, during the most important moment of the liturgical year? Well, history comes to help, as it often does. You see, these religious associations, formed by lay people, were born almost 1000 years ago, in the early 12th century, with the aim of helping out the less fortunate in their communities and of increasing the interest in and respect of liturgy and religious practice.

Members of the Confraternita di Santa Caterina, in Pietra Ligure. Because of their red cape, they are also known as “the reds” (Photo: Gianni Cenere)

In the quaint little town of Pietra Ligure, on the Italian Riviera, just as in the whole region, confraternite are a serious thing, where faith, tradition and heritage mix together. I happen to know a lot about them, because I had the immense luck to live there for four years: a time of serenity and happiness, certainly enhanced by breathtaking beauty of the place and by the friendship and sense of community I enjoyed thanks to its people.

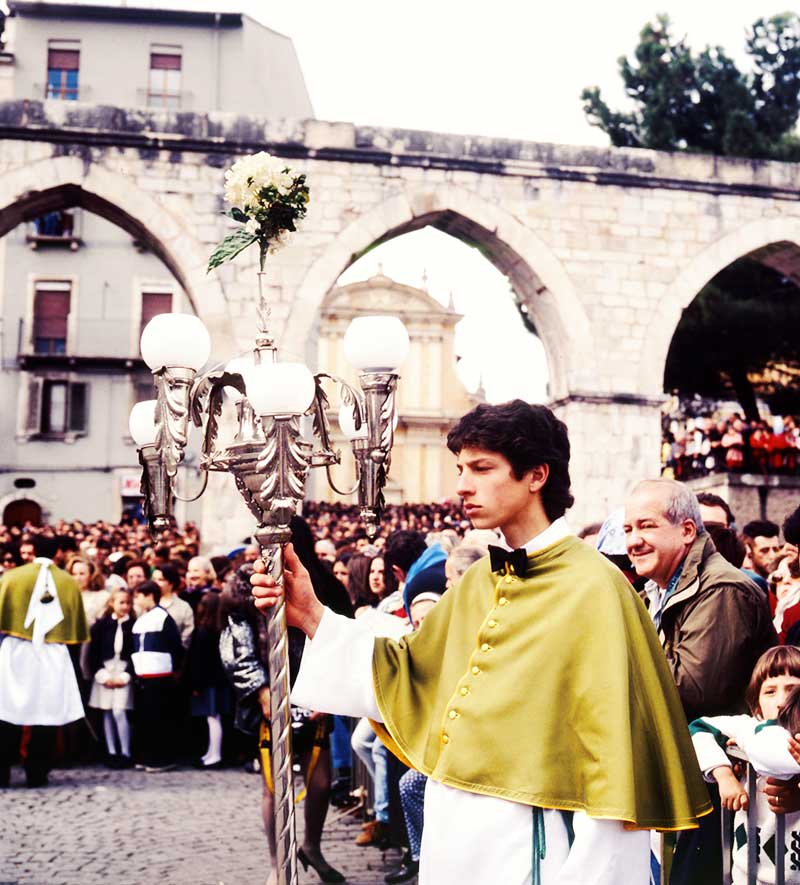

In Sulmona, Abruzzo, the Confraternita di Santa Maria di Loreto, known as lauretani, are protagonists of one of the most curious Easter traditions in town

Here, two confraternite share the stage: that of Santa Caterina and that of Orazione e Morte (of prayer and death). The Confraternita of Santa Caterina, also known as dei rossi, from the color of the cape they wear on their white tunics, are in charge of the Oratorio della Santissima Annunziata, which has been restored thanks to their work and which they maintain in all its beauty. In it, locals can pray and admire the beautiful crosses the Confraternita’s members carry by hand during holy processions: breathtaking pieces of art carved in wood, adorned on each of the cross’ arms and on its top by delicately made gold and silver decorations. As light as air and filigree, the look, the gentle, chimes-like sound they make while moving following the rhythm of the carrier’s steps. Carrying these crosses is an exercise of physical strength, training, faith and tradition that keeps on being passed on to the younger generations, a fact symbolised by how the Confraternita’s younger members learn how to carry crosses very early, and practice during holy processions with smaller, lighter versions of those held by adults. And on Holy Thursday, i rossi are also in charge of the preparation of the Cenacolo, or “sepurtu” in Pietrese dialect, another sign of their continuous presence and work within the spiritual fabric of the town.

Re-enactment of the Stations of the Cross, by members of a confraternita © Francesca Sciarra | Dreamstime.com

And then, there is the Confraternita of Orazione e Morte, also known as dei neri, because of the color of their uniform, a black tunic and a black hood covering the whole of its members’ face, two small slits left for the eyes. Born in 1633, its duty has always been that of keeping the cult of the Holy Sacrament fervent, of praying for the dead and of taking care of the burial of paupers. In times of pestilence and immense poverty, they would remove with dignity bodies abandoned in public places and make sure they received a funeral. They would also assist those sentenced to death in the moments leading to their execution. I remember how, when i neri were fully re-established as an active confraternita a few years back, some people found them frightening and “inappropriate,” because of their name and of the color of their uniform. But it was the hoods, those conic black hoods that kept its members’ anonymous, to create havoc for real: they were too scary for the people of the 2010s. Well, capable local historians gently reminded complainers the hood was originally created to make sure the confraternita members would carry out their duty without being recognized, so that they could not wallow in the fact they served with faith and humbleness their community. An important symbol, that needed to be kept and respected.

Santini della Vergine

In the south of Italy, we’ll meet the Arciconfraternita del Carmine, in Taranto: officially founded in 1645, they are active throughout the year, but it is during the Holy Week that their work truly leaves the mark. They are in charge of the ancient Processione dei Misteri, that has been taking place of Holy Friday since the late 16th century. Originally, only the statues of the Dead Christ and Our Lady of Sorrows were carried in the streets of old Taranto, but today, a bona fide crowd of beautiful sculptures is part of the procession: all of them carried by hand by the members of the Arciconfraternita del Carmine.

Members of the Arciconfraternita del Carmine, Taranto, with their white robes, capes and hoods © Francesca Sciarra | Dreamstime.com

In Sulmona, Abruzzo, the Confraternita di Santa Maria di Loreto, known as lauretani, are protagonists of one of the most curious Easter traditions in town, that of the Madonna che scappa in Piazza, or the Virgin that runs in the square. Yes, you read it right, and that’s exactly what happens. The whole ritual is a sort of theatrical representation, with the statue of the Virgin, that of Christ Resurrected and others literally acting their part, always held on their shoulders by lauretani. The climax of the ceremony is when, at 12 on Easter Sunday, thanks to a series of secret mechanisms known only to the members of the Confraternita, the black cloak covering Mary’s shoulders, symbol of mourning for the death of her son, falls to the ground, because he resurrected. Twelve doves are released in the skies, and the lauretani start running, the precious statue on their shoulders, for the accomplishment of a traditional act that leads many to tears.

Tradition, heritage and identity are not only kept alive by confraternite, but also by a series of rituals rooted in our national and cultural past, a past made of spirit, of art, of beauty and mystery. Once upon a time, the Officium Tenebrarum was a regular part of the Holy Week everywhere in the Catholic world. It was part of the liturgy and, in fact, it still is, but not many parishes practice it, because it’s a ceremony entirely in Latin, it’s in the evening, it’s long: not really what today’s world wants to participate to. It takes place on the Wednesday of Holy Week and, at the end of it, the whole church is shrouded in darkness and silence. And it’s then that the Miserere is intoned, a moment of touching beauty, when one thinks to the thousands and thousands of people who stood just there, throughout the centuries, listening to those words, praying the same way, breathing the same air. In the rare occasion when, today, the office is proposed, it is incredible to note how many people attend, in spite of the length, of the midweek date, of the Latin: many do it for faith, of course, but many also do it because there is a sense of connection with the heart of our tradition in it, with a past that makes one what we are and perhaps, for someone, of memories of holding hands with grandma and grandpa, all those years ago, when “andare alla messa con nonna” was the ultimate treat, because nonna would let you light candles in church and buy you ice cream afterwards.

Italy is a country built on a history repleting with spirituality that marked its identity from an artistic and cultural point of view, but also when it comes to heritage and memories: it is of this reality, a reality made of rituals and confraternite, of music and prayers, of communities unified in heritage and values, that the Italian Easter also tells us about. In a time where the past often is neglected, if not forgotten, and the essence of Man ridiculed, tradition and heritage remain the most beautiful example of what our country is, of where each and everyone of us comes from. An example bringing together the faithful and the non-faithful, the young and the old, the man and the woman, the rich and the poor, all sharing memories and values as old as Italy itself, never truly lost, never truly forgotten.