Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci might be famous for their early explorations of the New World, yet another Italian adventurer who commanded a four-year expedition to the Pacific Northwest, the Philippines, Australia and New Zealand—said to be one of the greatest scientific expeditions of the day—is virtually unknown today.

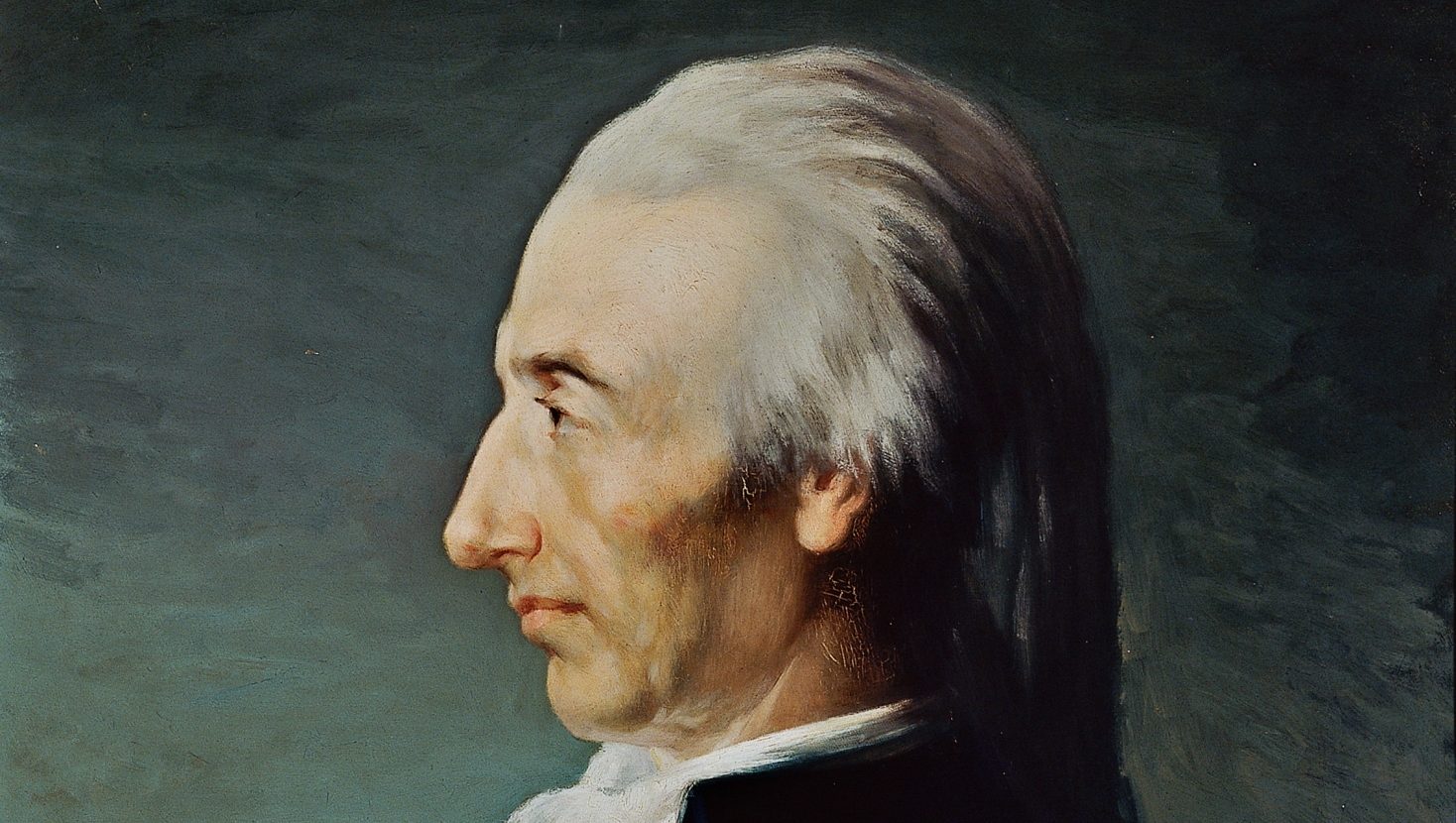

Alessandro Malaspina, born in Mulazzo, Tuscany, in 1754 and raised in Palermo, sailed under the Spanish flag, as did Columbus and Vespucci. During his round-the-world voyage, Malaspina meticulously documented the native tribes, plants and coastal areas of the Pacific Northwest. After returning home, though, he was accused of plotting against the Spanish government and jailed. Accounts of his voyage were all but lost until recent years.

In Malaspina’s day, several ministers in the Spanish court were Italians, including Giovanni Fogliani, Malaspina’s great-uncle. This familial connection enabled the young Italian to enter the Spanish navy, where he excelled. After distinguishing himself during a naval battle against Great Britain, he was promoted to captain at the age of 26.

In 1782, Malaspina made his first round-the-world voyage, a trip that took two years. A few years later, the young Italian himself proposed another voyage to survey Spanish outposts in the Americas and the Philippines. His plan was approved and he was given command of two ships, Descubierta (“Discovery”) and Atrevida (“Daring”).

The expedition had two goals: To increase geographic and scientific knowledge and to assess the health of Spain’s vast empire, especially along the west coast of North America where the British and Russians were expanding their spheres of influence.

The voyage was meticulously planned and well-funded. Anything the Italian explorer needed, from scientific instruments to tools and medicine, was made available. Members of Turin’s Academy of Sciences were consulted on the mission’s scientific aims, and several scientists accompanied the crew. Ethnographers and artists were on hand to study and record the indigenous peoples they would meet.

After two years of preparation, the party set sail from Cadiz on July 30, 1789, bound for South America. They rounded the Horn and sailed up the Pacific coast to Mexico. While resupplying in Acapulco, Malaspina received word that his course had been altered. King Carlos IV wanted him to detour to Alaska and survey the coastline between Mount Saint Elias and Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. His task: To find out whether a northwest passage from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic existed.

Malaspina’s vessels reached Yakutat Bay in present-day Alaska in June 1791 and anchored there for a month, allowing expedition scientists to study the Tlingit people, a Northwest coastal tribe. The scientists recorded the tribe’s customs, language, warfare methods and burial practices. Artists sketched portraits of tribal members and scenes of Tlingit daily life. A botanist collected and recorded numerous new plants. Today, a glacier between Yakutat Bay and Icy Bay is known as the Malaspina Glacier.

Malaspina knew that the British explorer James Cook had surveyed the west coast of Prince William Sound about 15 years earlier and had not found a northwest passage. Rather than spend more time, the Italian set sail for the Spanish outpost at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island, established two years earlier. There, his crew was delighted to find a thriving vegetable garden and a bakery.

On Vancouver Island, Malaspina’s men made detailed geographic surveys while ethnographers studied the Nootka peoples. Thanks to trinkets and other gifts they had on board, the Italians made friends with tribal members, including their powerful chief.

The men surveyed and mapped Nootka Sound with a far greater degree of accuracy than previous attempts had managed. Botanical studies and several experiments were carried out, including trying to make beer from pine needles to combat scurvy. After resupplying the vessels, the expedition set sail again, leaving the outpost soldiers with medical supplies and tools.

Malaspina entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca, near present-day Seattle, and continued south to explore the mouth of the Columbia River, now the border between Washington and Oregon. Unsuccessful at locating a northwest passage, he made a final stop at the Spanish settlement and mission in Monterey, Calif., before sailing on to the Philippines, New Zealand and Australia. After a rest in Tonga, the expedition sailed back to Spain, arriving in Cadiz in September 1793—a voyage of more than four years. They were greeted with great acclaim, and Malaspina was received by King Carlos.

The glory days did not last long, however. A year later, Malaspina was arrested on suspicion of disloyalty, receiving a life sentence. In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte personally intervened on his behalf. The explorer was finally released, but more than eight years in prison, much of it in solitary confinement, had ruined his health.

While imprisoned, Malaspina’s personal papers were seized along with documentation from the expedition. His proposed seven-volume account of his round-the-world journey, intended to surpass the one published by James Cook, was never realized. As his contemporary, naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, remarked: “This able navigator is more famous for his misfortunes than for his discoveries.”

Malaspina died in his home town of Mulazzo, Italy at the age of 55. Although several articles and the explorer’s journals were published in the 1800s, only recently was a multi-volume record of his expedition published by the Naval Museum in Madrid.