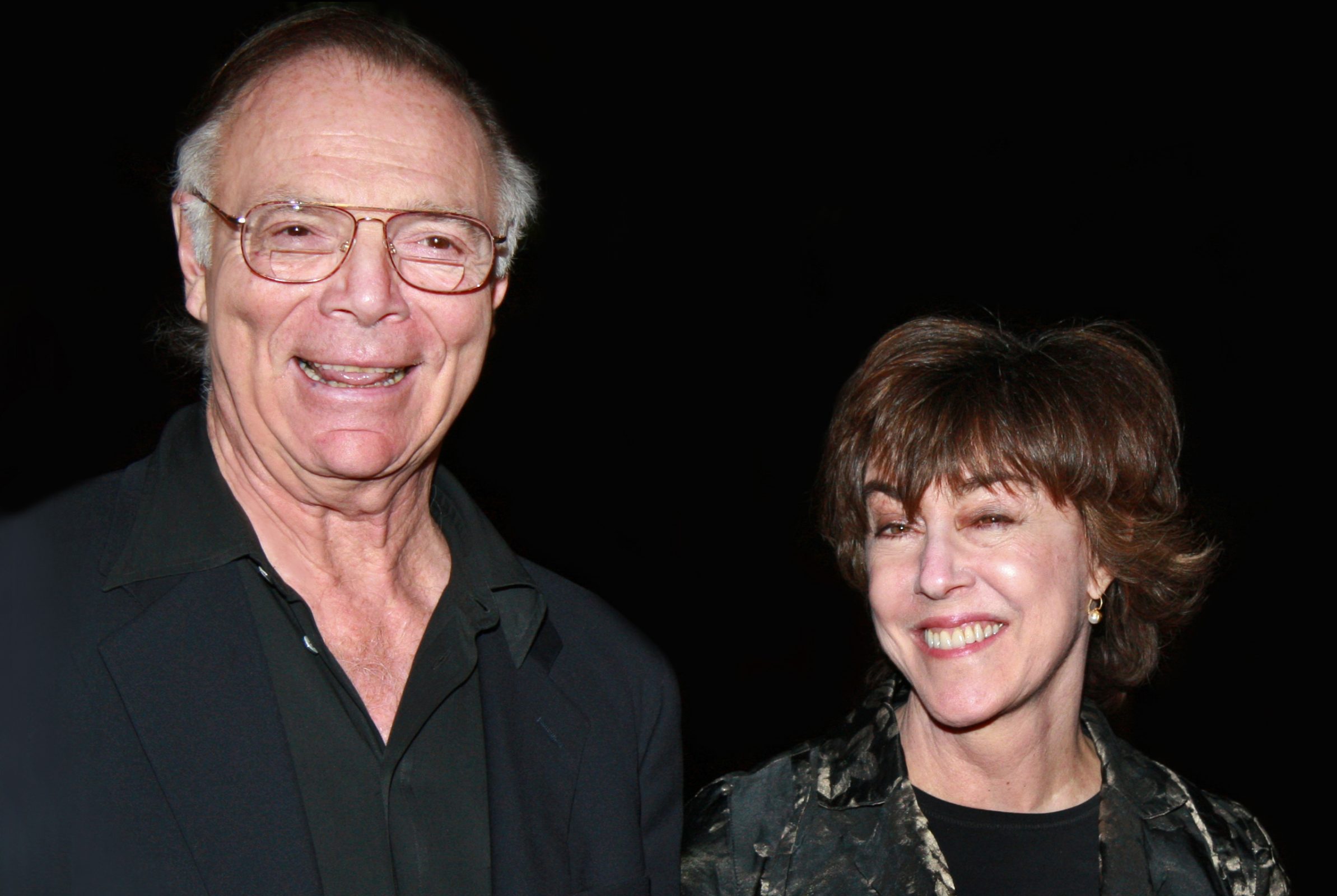

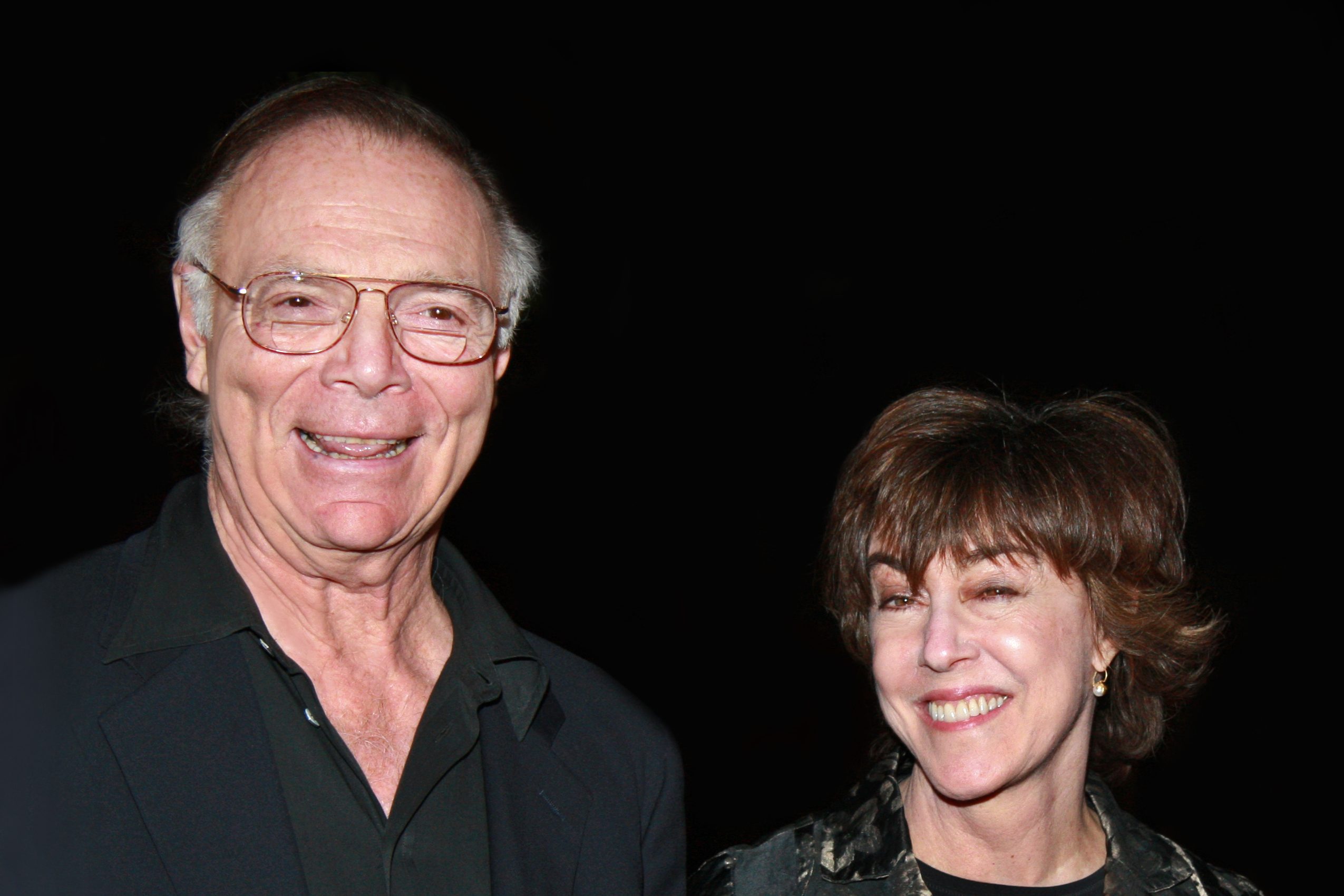

The legendary Nicholas Pileggi

Nora Ephron once wrote, “The secret to life, marry an Italian.” She was referring to her husband, journalist and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi. Ms. Ephron, who in her own right was a best-selling author and filmmaker, married Pileggi in 1987 and was with him until she sadly passed away in 2012. Despite his profound loss, Nicholas Pileggi continues to work at the age of eighty-seven and remains one of the most influential writers in the 21st century.

As we continue to live in the middle of a pandemic and confront so many unknowns for the next several months, I wondered how the legendary writer was spending his time. “Writing scripts. Writers are naturally quarantined, it is part of our life,” Pileggi replied. By nature writers tend to go underground, so to speak. Most authors are creatures of habit and spend a large portion of the day writing in solitude. No matter the crisis, Pileggi’s routine as a writer has remained the same for over fifty years.

Nicholas Pileggi, born in 1933, was raised in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. The area served as a foundation to his interest in writing about organized crime. He noticed that the men from his neighborhood never worked and were always impeccably dressed. Those street observations proved useful in Nick’s early career as a police reporter.

He was determined to follow a different path than his father. Nick’s dad Nicola was an emigrant from Calabria. His father was a cinema musician and a proprietor of a shoe store. Nick’s mother, Susan Defaslo, and father stressed the value of education. They wanted their son to have endless opportunities.

Nick graduated from New Utrecht High School and attended Long Island University in New York City. While in college he was immediately interested in journalism. “During my junior year at LIU in 1956, I worked for the AP as a nighttime copyboy. Many of the reporters and editors helped me learn and I was hired after I graduated,” said Pileggi.

Long before his NY Times bestseller Wiseguy (1985), which turned into one of the all-time American movie classics Goodfellas (1990), Nick Pileggi was already an established journalist. At the time, there was a cadre of reporters who over a period of time grew tired of the editorial constraints with news articles.

Many wanted to write longer articles like acclaimed authors Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, David Halberstam and Gay Talese, who happens to be Nicholas Pileggi’s first cousin. “Actually,” said, Talese, “We’re double-first cousins: our mothers were sisters; and our fathers first-cousin emigrants from Calabria.” The cousins saw one another frequently as the Talese family travelled from Ocean City, NJ to Brooklyn, NY.

Like Talese, Nick was a vociferous reader and influenced by the literary greats. Pileggi jokingly remarked, “I was influenced by the usual boring list of writers. From Melville to Fitzgerald to TS Eliot and Salinger and on…” The two cousins entered the field of journalism around the same time independently from each other. Pileggi worked for AP and Talese, the New York Times. According to Talese, who is a year older than his cousin, in their younger days they “roomed together for more than a year until I was drafted into the Army in 1955.”

When I asked Gay (who is also glued to his computer writing extensively during this global pandemic) about why he thought his cousin and he followed the same profession, the author explained, “I think that, during that time period, children of immigrants—Jews, Italians, Irish, some blacks—found journalism a first step up socially as well as professionally. In those days, none of us had “elite” college degrees. We were lucky to get degrees of any kind. With the recent passing of Peter Hamill —he never went to college—it occurred to me that we less-formally-educated journalists had something over these elite news people we have today.”

For Pileggi, whom I find to be a man of few words who gets right to the point, journalists during his time “were not the enemy of the people. They reported on the enemy of the people to the people, as reporters still do today.” There has always been a level of respect that most reporters share for one another.

When young and old writers hear the name Nick Pileggi, the same level of respect enters their mind. He moved on from the Associated Press to New York Magazine in 1968. One of the primary reasons for the change was to have more freedom to write longer feature articles and to have time to write books. Aside from his book Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family, he wrote Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas (1995).

The book became the basis for the box-office hit Casino where Pileggi wrote the screenplay with movie director Martin Scorsese. Along with Mario Puzo, Nick Pileggi’s name is associated with some of the greatest mob movies ever created in American film. In my opinion, another contributing factor to Nick Pileggi’s legacy is the way he changed the language of journalism in the 21st century.

Pileggi’s stories have certainly influenced news editors when covering organized crime figures. In New York City there are two tabloid newspapers, the Post and the NY Daily News. Both use intertextuality, or what is called wordplay headlines in order to grab the readers’ attention. For example, it is not uncommon for these periodicals to print wordplay headlines based on the movie title Goodfellas or his book Wiseguy.

One headline read, Sobfella when a mobster was whining about his prison conditions, as another published Criesguy. No doubt Pileggi’s writing has influenced news headlines. His usage of words like whacked, wiseguy, and goodfella (told to him by his contacts in the mob, but mainstreamed by him) appear regularly in our lexicon.

Ironically, Nick’s uncle Joe (Gay Talese’s father) would always yell at him and say, “Why don’t you write about Michelangelo or Leonardo da Vinci instead of organized crime,” Pileggi’s response was always consistent, “Find me an editor who wants to know more about Michelangelo or da Vinci and maybe I will.”

Nick understood his uncle’s concern about the image of Italian Americans but also added, “I’m still trying to figure out how being Italian American has impacted my life” and promised, “When I find out I will tell you.” Two things we know for certain about the legendary Italian American Nick Pileggi is how Nora Ephron revealed her secret for a happy marriage in a six word autobiography, and why he is greatly respected in the field of journalism.

Nora Ephron una volta scrisse: “Il segreto della vita, sposare un italiano”. Si riferiva a suo marito, giornalista e sceneggiatore Nicholas Pileggi. La signora Ephron, che a sua volta era un’autrice e regista di best-seller, ha sposato Pileggi nel 1987 ed è stata con lui fino alla sua triste scomparsa nel 2012. Nonostante la sua profonda perdita, Nicholas Pileggi continua a lavorare all’età di ottantasette anni e rimane uno degli scrittori più influenti del XXI secolo.

Mentre continuiamo a vivere nel mezzo di una pandemia e ad affrontare tante incognite per i prossimi mesi, mi chiedevo come passasse il tempo il leggendario scrittore. “Scrivendo sceneggiature. Gli scrittori sono naturalmente in quarantena, fa parte della nostra vita”, risponde Pileggi. Per natura gli scrittori tendono ad stare sottoterra, per così dire. La maggior parte degli autori sono creature abitudinarie e passano gran parte della giornata a scrivere in solitudine. Indipendentemente dalla crisi, la routine di Pileggi come scrittore è rimasta la stessa per oltre cinquant’anni.

Nicholas Pileggi, nato nel 1933, è cresciuto a Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. La zona è servita da base al suo interesse per la scrittura sulla criminalità organizzata. Notò che gli uomini del suo quartiere non lavoravano mai e che erano sempre vestiti in modo impeccabile. Quelle osservazioni da strada si sono rivelate utili nella prima carriera di Nick come reporter di polizia.

Era determinato a seguire una strada diversa da quella di suo padre. Il padre di Nick, Nicola, era un emigrante calabrese. Suo padre era un musicista di cinema e proprietario di un negozio di scarpe. La madre di Nick, Susan Defaslo, e il padre sottolineavano il valore dell’educazione. Volevano che il figlio avesse infinite opportunità.

Nick si è diplomato alla New Utrecht High School e ha frequentato la Long Island University di New York. All’università si è subito interessato al giornalismo. “Durante il mio terzo anno alla LIU, nel 1956, ho lavorato per l’AP come fattorino notturno. Molti dei giornalisti e dei redattori mi hanno aiutato ad imparare e sono stato assunto dopo la laurea”, ha detto Pileggi.

Molto prima del suo bestseller del NY Times Wiseguy (1985), che si è trasformato in uno dei classici del cinema americano di tutti i tempi Goodfellas – Quei bravi ragazzi (1990), Nick Pileggi era già un giornalista affermato. All’epoca, c’era un gruppo di giornalisti che nel corso del tempo si era stancato dei vincoli editoriali degli articoli di cronaca. Molti volevano scrivere articoli più lunghi, come gli acclamati autori Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, David Halberstam e Gay Talese, che si dà il caso sia il cugino di primo grado di Nicholas Pileggi. “In realtà”, diceva Talese, “siamo due volte cugini di primo grado: le nostre madri erano sorelle; e i nostri padri emigrati dalla Calabria erano primi cugini”. I cugini si vedevano spesso quando la famiglia Talese viaggiava da Ocean City, NJ, a Brooklyn, NY.

Come Talese, Nick era un lettore vorace ed è stato influenzato dai grandi della letteratura. Pileggi ha commentato scherzosamente: “Sono stato influenzato dalla solita noiosa lista di scrittori”. Da Melville a Fitzgerald, a TS Eliot e Salinger e via dicendo”. I due cugini sono entrati nel campo del giornalismo più o meno nello stesso periodo, l’uno indipendentemente dall’altro. Pileggi ha lavorato per AP e Talese, per il New York Times. Secondo Talese, che ha un anno più di suo cugino, da giovani “hanno vissuto insieme per più di un anno fino al 1955, anno in cui sono stato arruolato nell’esercito”.

Quando ho chiesto a Gay (che è incollato al suo computer a scrivere molto durante questa pandemia globale) come spiegava che sia suo cugino sia lui avessero scelto la stessa professione, l’autore ha spiegato: “Penso che, in quel periodo, i figli degli immigrati – ebrei, italiani, irlandesi, alcuni neri – abbiano trovato nel giornalismo un primo passo in avanti sia socialmente che professionalmente. A quei tempi, nessuno di noi aveva una laurea “d’elite”. Siamo stati fortunati ad avere lauree di qualsiasi tipo. Con la recente scomparsa di Peter Hamill – non è mai andato al college – mi è venuto in mente che noi giornalisti istruiti meno formalmente avevamo qualcosa in più rispetto a questi giornalisti d’elite che abbiamo oggi”.

Per Pileggi, che trovo un uomo di poche chiacchiere che va dritto al punto, i giornalisti ai suoi tempi “non erano nemici del popolo. Hanno denunciato il nemico del popolo al popolo, come fanno ancora oggi i giornalisti”. C’è sempre stato un livello di rispetto che la maggior parte dei giornalisti condivide uno per l’altro.

Quando giovani e vecchi scrittori sentono il nome di Nick Pileggi, lo stesso livello di rispetto attraversa la loro mente. Nel 1968 è passato dall’Associated Press al New York Magazine. Uno dei motivi principali del cambiamento è stata la maggiore libertà di scrivere articoli più lunghi e di avere il tempo di scrivere libri. A parte il suo libro Wiseguy: La vita in una famiglia mafiosa, ha scritto Casino: Amore e onore a Las Vegas (1995).

Il libro è diventato la base del successo al botteghino di Casino, dove Pileggi ha scritto la sceneggiatura con il regista Martin Scorsese. Insieme a Mario Puzo, il nome di Nick Pileggi è associato ad alcuni dei più grandi film di mafia mai realizzati nel cinema americano. A mio parere, un altro fattore che contribuisce all’eredità di Nick Pileggi è il modo in cui ha cambiato il linguaggio del giornalismo nel XXI secolo.

Le storie di Pileggi hanno certamente influenzato i redattori dei telegiornali quando si occupano di criminalità organizzata. A New York ci sono due tabloid, il Post e il NY Daily News. Entrambi usano l’intertestualità, o i cosiddetti titoli con giochi di parole, per catturare l’attenzione dei lettori. Per esempio, non è raro che questi periodici stampino titoli di testa con giochi di parole basati sul titolo del film Goodfellas o sul suo libro Wiseguy.

Un titolo fu Sobfella, quando un mafioso si lamentava delle condizioni di prigionia, come un altro pubblicato fu Criesguy. Senza dubbio la scrittura di Pileggi ha influenzato i titoli delle notizie. Il suo uso di parole come whacked, wiseguy, e goodfella (raccontati dai suoi contatti nella mafia, ma da lui resi mainstream) appaiono regolarmente nel nostro lessico.

Ironia della sorte, Joe, lo zio di Nick (il padre di Gay Talese), gli urlava sempre contro e gli diceva: “Perché non scrivi di Michelangelo o Leonardo da Vinci invece che del crimine organizzato”, la risposta di Pileggi è sempre stata coerente, “Trovami un editore che voglia saperne di più su Michelangelo o da Vinci e forse lo farò”.

Nick capiva la preoccupazione dello zio per l’immagine degli italo-americani, ma aggiungeva anche: “Sto ancora cercando di capire come l’essere italo-americano abbia influito sulla mia vita” e mi ha promesso: “Quando lo scoprirò te lo dirò”. Due cose che sappiamo per certo del leggendario italo-americano Nick Pileggi sono il modo in cui Nora Ephron ha rivelato il suo segreto per un matrimonio felice in un’autobiografia di sei parole, e il motivo per cui è molto rispettato nel campo del giornalismo.